Editor’s Note: This is an updated post from August 2018. The updated version appeared on MinnPost on October 23.

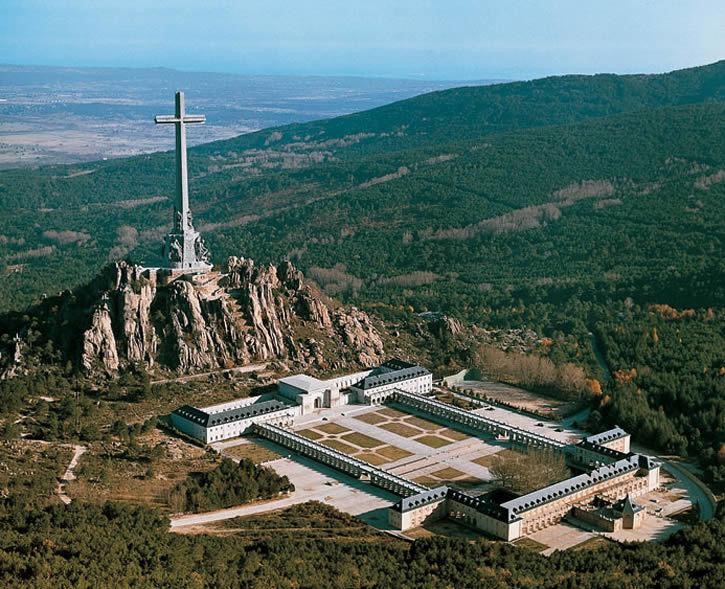

Today the Spanish government removed the corpse of General Francisco Franco from the Valley of the Fallen, a grandiose mausoleum and basilica near Madrid that the Dictator had designed to eternally enshrine his victory in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). After much criticism and legal battles, Franco’s remains were moved to a family tomb in a cemetery in the outskirts of the capital.

Why has it taken so long to remove the body of a dictator from a sanctuary that celebrates his rule?

A Pact of Oblivion

In contrast to the ways we currently understand democratization efforts, the success of Spain’s Transición (the period between the death of Franco in 1975 and the completion of the new Constitution in 1978) was predicated on the assumption that the past is the past, and that silence is the key to paving the way to peace. Spain rapidly transitioned from authoritarianism to democracy, integrated into Europe, and achieved unprecedented economic prosperity. All these changes took place with no attention paid to the crimes committed and suffering inflicted by the Franco regime.

As a result of this unwritten “Pact of Oblivion,” the public presence of Francoist symbols remained largely untouched. The city of Madrid, in which I grew up during the years of the nascent democracy, had numerous visible signs of the dictatorship. The Valley of the Fallen was not an exception. The entire country was decorated with monuments, statues of the Dictator in parks and squares, and plaques in memory of the ‘‘Fallen for God and for Spain’’, which honored only those who perished in the war on the Francoist side. The one and five Peseta coins that I received as part of my allowance had Franco’s likeness engraved with the words “Francisco Franco. Leader of Spain by the Grace of God.” This currency was slowly removed from circulation but continued to be accepted as legal tender until the arrival of the Euro in 2002.

Beyond those immediately scarred by the dictatorship’s terror, the context and meaning of these Francoist symbols and monuments were progressively forgotten, as was the socio-political reality to which they bore witness. But with the turn of the century and the rise of a generation that had come of age in a modern, European, Spain, those old rusty statues and plaques, and the Franco mausoleum itself, started being looked at again with fresh eyes. The Valley of the Fallen is also the final resting place of Falangist Party founder Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera and contains the remains of some 35,000 civilians and soldiers, many of them Republicans executed by Franco’s regime, and transferred to the site on his orders. Many were startled by this spectral anachronism: an active Fascist monument in Europe?

Memoria Histórica

In the 2000s, grassroots efforts began to locate and exhume the mass graves of the Republican victims of the Civil War and the Franco regime. The emergence of a strong social movement led by the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARMH) opened up intense debates about the way Spain had dealt, or rather not dealt, with the dictatorship and its victims. Spaniards started to look at the country’s past as Europeans and global citizens, and this involved playing catch up with Western Europe’s direct engagement and openly public wrestling with the memory of their own compromised or authoritarian regimes.

The Holocaust’s increased centrality to European memory politics contributed significantly to raising awareness in a new generation of scholars, artists, journalists, and activists regarding Spain’s blood-soaked past. Becoming European meant critically revisiting this, so to speak, Spanish Sonderweg, regarding the transition to democracy. Part of this dramatic paradigm shift in thinking about the Spanish past ultimately reframed the discussion, adopting terms and ideas around transitional justice, victims’ rights, and memorialization consistent with other nations on the continent.

The exhumation of corpses provided explicit undeniable material evidence of the repressive policies put in place by Franco and sparked an ongoing and emotional public debate over the regime’s concretely identifiable remains, including the Valley of the Fallen.

Irreconcilable narratives

In 2007 the Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) challenged for the first time the status quo with regards to public (non)remembrance of the Civil War and Francoism and proposed a bill for a law commonly known as Ley de Memoria Histórica (Historical Memory). The law was approved by the Parliament and included among its provisions the removal of Francoist symbols from public buildings and spaces. The Memory Law also called for measures to democratize the Valley of the Fallen, but recommendations of a commission appointed in 2011, were ignored during the following years of conservative Popular Party rule (2011-2018). The switch in governments last year brought the question concerning Franco´s remains and the mausoleum back on the center stage of the political agenda.

My colleague Francisco Ferrándiz, whom we hosted on two occasions at CHGS, was one of the members of the 2011 commission. In an interview he stated that “what we advocate for in our report goes beyond the Franco exhumation itself. We underscore the need to resignify the monument (…) the Francoist hierarchy of the site needs to be dismantled”.

While scholars of genocide and transitional justice, and memory activists across the globe will see such recommendations as a matter of reparation and a basic requirement of democratic life, Spanish society seems to be afraid of confronting this difficult past.

At the core of the Spanish memory, conflict are two irreconcilable narratives. The center-right People’s Party –unsurprisingly, given its historical affinity with the pre-democratic regime – stubbornly sticks to the language of the Transición, as if the country was still on the brink of fratricide. For “reconciliation” to happen, they claim, one should not drudge up the pain of the past. The left, however, highlights the unaccounted for atrocities that were committed by the Franco regime both during the war and the forty-year dictatorship that followed.

There is an insurmountable distance between those who advocate for remembrance as a way of reparative justice and democratic education vs. those who see in forgetting a political virtue. An op-ed in the main conservative newspaper ABC last year, commenting on the governmental decision to dig up Franco from his celebratory resting place, could not characterize the latter position more vividly. The author welcomed the fact that his eleven-year-old son had not the slightest notion of this dark chapter of Spanish history. When driving past the Valley of the Fallen, and to the question “Daddy, who was Franco?”, he decided not to respond and changed the subject. The liberal papers, however, are welcoming the news of the exhumation and relocation. The most repeated word in these circles is: “Finally”.

The Spanish case invites reflections that go beyond its borders, resonating more broadly, not the least in the US. Why maintain monuments, if their foundations cry out for total reevaluation? What if we always lived with the discomfort of their symbolism, the very idea of why this structure existed in the first place? What if when we walked by them, and instead of welcoming us to remember, it was imperious, imposing, and upholding an ideal that wounds us instead?

The exhumation and the challenging process of reclaiming the Valle de Los Caídos for all of Spain’s people will undoubtedly be a source of friction. But in the end, even those who oppose Memoria Histórica will have to recognize that demystifying the most divisive symbol of the dictatorship, does not open old wounds but may help to close them finally.

Alejandro Baer is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Minnesota and the Stephen C. Feinstein Chair in Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

Comments