We have grown accustomed to seeing photographs captured during conflict dehumanizing victims and fetishizing their suffering. Our Eye on Africa column has previously discussed the disproportionate ways in which the pain of non-western victims is consumed through the media, even though it does not educate us about the context leading to the suffering. Yet, other forms of war-photography capture something else: everyday life under conflict. Instead of focusing on the pain and suffering of victims, these photographs aim to highlight the continuity of life. They focus on the possibility of a future and the necessity to maintain a sense of self. Conflict and suffering can in fact be captured in ways that do not always freeze moments of agony and death in eternity.

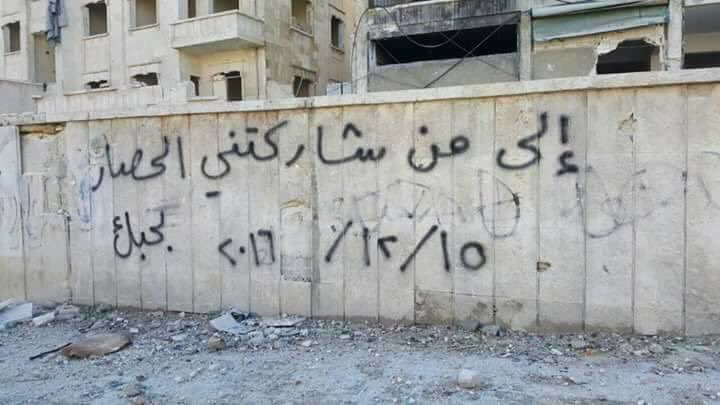

These images of graffiti in Aleppo depict stories of love. Graffitied, above, is “To the woman who shared the siege with me: I love you. 15/12/2016.” Getting ready to flee Aleppo in the wake of violence between Bashar al Assad and opposition, Marwa and Salih took up graffiti to document their love for each other on buildings destroyed by the war. However, love is not just reserved to their romantic relationship, but extends to their homeland. Below, sprayed on the walls of a fallen building they wrote, “We shall return, love. 15/12/2016”. These words are from a song by Lebanese singer, Fairouz, who sang to Lebanon in the wake of years of Civil War. Thus, illuminating the ambiguous “love” to evoke Aleppo, their home.

We have seen such images before. CHGS has in its collection 69 original photographs taken by Maxine Rude of the daily life of survivors in Displaced Persons camps established in Germany and Austria at the end of World War II. Here, we see Henryk Michinek, a displaced person, painting a mural at a Children’s Center in Germany. Maxine elaborates, “It was always such a revelation seeing the art done by those in the camps. So much was dark and heavy, often reflecting the justice that had vanished from their lives.”

Art has the profound capacity to document and depict the devastating consequences of war and conflict: whether it’s through song, or graffiti, or murals. But art also has the ability to highlight what is important for people to dwell on, and photographs that capture such moments are capable of portraying everyday life during conflict. Perhaps it is precisely this contrast that has the power to illustrate the extent of suffering, but also the ways in which art is a form of coping, resistance, and resilience.

Miray Philips is a Ph.D. graduate student in Sociology with a focus on conflict, identity, and collective memory in the Middle East and North Africa. Miray’s current research is focused on how Copts in the diaspora make sense of and respond to current events in Egypt. She is also the 2016-17 Badzin Fellow.

Wahutu Siguru contributed to this post. Wahutu is a PhD Candidate in the Sociology Department at the University of Minnesota. Wahutu’s research interests are in the Sociology of Media, Genocide, Mass Violence and Atrocities (specifically on issues of representation of conflicts in Africa such as Darfur and Rwanda), Collective Memory, and perhaps somewhat tangentially Democracy and Development in Africa.

Comments