“Beautiful feelings make for bad literature.” French literary tradition has proved André Gide’s assertion wrong, of course. “Beautiful feelings” of empathy and commitment to equity infuse Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables and Emile Zola’s Germinal, which have remained on the international bestseller list for over a century.

Curiously post-1945 programs for reconciliation, another “beautiful feeling,” among European formerly enemy nations, and which led to the establishment of the European Union (EU), have not inspired a Transeuropean literature. Robert Menasse’s widely translated novel Die Hauptstadt is an exception.

The Austrian writer and enthusiastic supporter of European integration by his own admission, pens a darkly satirical tale in which self-centered EU bureaucrats invent a “Big Jubilee Project” around the theme of “Auschwitz” to mark the 50th anniversary of the EU Commission. Historical facts are wrong, this is, after all, fiction, but the novel provoked heated controversies in the German-speaking world. Critics felt that the novel “cheapened” the Holocaust by distorting its role in the foundation of the EU.

It may be that “beautiful feelings”make for good literature only when catastrophe is involved. But how to invoke empathy and peaceful conflict resolution in the midst of an ongoing catastrophe such as the Israel-Palestine conflict?

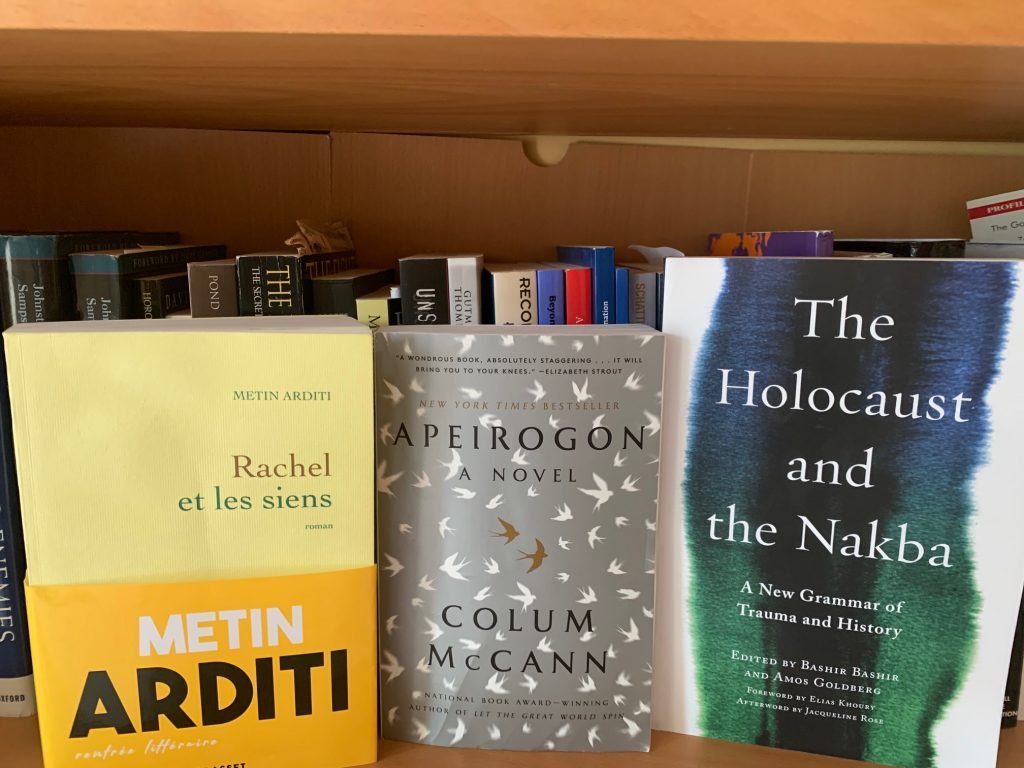

Three recent and very different books provide a similar response: look to literature. The Holocaust and the Nakba: A New Grammar of Trauma and History is an edited volume of social science; Apeirogon and Rachel et les siens are novels based on historical facts.

Half of The Holocaust and the Nakba consists of comments on literary works, with pride of place given to Lebanese-born Elias Khoury searing novel Children of the Ghetto, the fictional memoir of Palestinian expatriate Adam Dannoun, who was born during the all too factual Lydda massacre of Palestinians by Israeli soldiers during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Co-editors Bashir Bashir and Amos Goldberg, who presented their book at CHGS in October 2020, acquaint their readers with a much lesser-known Jewish Israeli literature also, which reflected in the late 1940s and 1950s “the feeling that the plight of Palestinians refugees bore a remarkable resemblance to that of the European Jews.”Mendel Man’s An Abandoned Village (1956), written in Yiddish and published in Hebrew, exemplifies this feeling, which was not confined to radical left-wing Zionist publications.

Metin Arditi’s novel Rachel et les siens (only available in French) offers a passionate and highly readable account of Jewish Israeli and Arab Palestinian’s intertwined fates under 70 years of Ottoman rule, the British mandate, and Israeli rule. Rachel, an Arab-speaking Sephardi Jew, grows up with her adopted Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi sister in a middle-class home shared with a Christian Arab family in Jaffa. Already as a child, Rachel writes a theater play, which highlights the growing rivalry over land between Arabs and Jews and pleads for cohabitation. Multilingualism is both a practical necessity and a norm to be cherished. In 1937 she loses her daughter and her husband, a philosopher trained by Martin Buber, to a terrorist attack committed by Arab Palestinians.

To hide the identity of her second daughter’s father, she moves from Tel Aviv to Istanbul and then Paris, where her plays are staged to critical acclaim. But she scolds herself for her “lies.” Eventually, she returns to Israel to help raise a beloved handicapped grandson, whose genetic make-up includes Arab Palestinian and Jewish Israeli ancestry. The melodramatic plot stretches credibility at times, and yet self-reflective accounts of the protagonists compel the reader to identify with many Others.

Colum McCann’s Apeirogon is part novel and part factual account of two tragedies: Jewish Israeli Rami Elhanan lost his 13-year-old daughter Smadar to a Palestinian suicide bomber in Jerusalem in 1997 and Muslim Palestinian Bassam Aramin his ten-year daughter Abir in 2007 to an Israeli soldier’s bullet in front of her school. Rami and Bassam had become friends well before Abir’s death through the organization Combatants for Peace, and they have spoken together against the vicious cycle of occupation and revenge in Israel and across the world many times since. The book draws the reader into the lived experiences of Palestinians and Israelis powerfully, although its 1001 narrative sections, several of which have no obvious relation to the main story, weakens emotional connection with Bassam, Rami, and their families’ heart-rending stories occasionally.

Arditi, Bashir, Goldberg, and McCann refuse to recommend a specific political solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict, be it a confederation, a federation, a one-state or two-state solution. Their books express, however, similar “beautiful feelings”: No, to nationalism and Occupation. Yes, to a binational solution for a joint Arab Israeli democratic dwelling. No, to the objectification of the other and silence. Yes, to speaking up authentically and listening. No, to conflating the Holocaust with the Nakba. Yes, to “empathic unsettlement,” which transforms “otherness” from a problem to be disposed of into a moral and emotional challenge. And yes to flawed political compromises and even reconciliation between the two peoples.

Considering the tragic renewal of violence last May in Israel and the occupied territories, isn’t this all pie in the sky? Renowned Israeli novelist Assaf Gavron acknowledges that books have little immediate impact. “Changes are made slowly and by small bits.” His advice to the writing profession: Be humble and keep writing. Arditi, Bashir, Goldberg, and McCann need not be reminded.

Catherine Guisan is an independent scholar and Associate Professor affiliated with the Department of Political Science, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Her research interests include European politics, politics of reconciliation, social movements for democratization, political theory. To read more of her work see: Un sens à l’Europe: Gagner la Paix (1950-2003), A Political Theory of Identity in European Integration: Memory and Policies, “Of Political Resurrection and ‘Lost Treasures’ in Soviet and Russian Politics.”

Comments