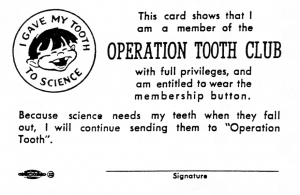

Baby Tooth Survey Pledge Card, Missouri Encyclopedia: https://missouriencyclopedia.org/groupsorganizations/baby-tooth-survey-st-louis

From 1959-1970, the communities of Saint Louis, Missouri were tasked with a unique mission: sending in the teeth of children to a newly formed initiative called the Baby Tooth Survey. Founded by physicians Louise and Eric Reiss, this project was in collaboration with Saint Louis University and the Washington University of Dental Medicine with the primary goal of proving the traces of radioactive contamination within children’s bodies. This radiation was caused by hundreds of atmospheric nuclear tests conducted by the U.S. government in Nevada, New Mexico, and the Marshall Islands. Strontium-90, one particularly harmful radioactive isotope, was contaminating water and dairy in the United States, thereby polluting milk products being consumed by children which would be absorbed into bones and teeth. The indisputable findings of harmful radioactive levels in children documented by this initiative led President John F. Kennedy to sign the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963, which banned all nuclear tests except those detonated underground. This harrowing narrative led by housewives and mothers plays an important role in the history of anti-nuclear activism, which is captured by director Hideaki Ito in his documentary film Silent Fallout: Baby Teeth Speak (2023).

Screened to an audience of students, faculty, and community members at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities and sponsored by the UMN Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine, and History, Silent Fallout is split into four chapters: Omens, Ground Zero, Baby Teeth, and Silent Heroes. Each section builds upon the previous, gradually weaving together a story not just limited to the United States, but one global in its breadth. From Japan to the Marshall Islands to the United Kingdom, what Ito makes clear is that the American victims of nuclear testing are not alone in their struggles. Opening the film is activist Mary Dickson, born 1955, a downwinder from Salt Lake City, Utah. “Downwinder” refers to those who were exposed to fallout from nuclear tests, and although Salt Lake City is located miles northeast from the Nevada Test Site, there are many cases of health complications in those areas, including Mary Dickson herself, revealing the reach and dangers of nuclear fallout that spread across the United States. What she expresses in these opening scenes is her disillusionment and anger towards the U.S government as she witnessed herself and her community fall ill to radiation poisoning without adequate support nor acknowledgement from the United States. This sets the tone for the rest of the film as Ito interviews other downwinders who express similar sentiments. Although the film does capture a transnational nuclear history, it remains very much fixed within an American context. One focus of the film and a reason for its screenings across North America is to educate the American public on the violence perpetrated by the U.S. government on its own people. The anger being expressed towards the United States by white American interviewees works to destabilize an American pride and trust towards the government and question the conditions around freedom and protection.

The main protagonists of the film are the downwinders, the housewives, and the mothers who headed this movement against nuclear testing, organizing protests and anti-nuclear projects that led towards the Partial Test Ban Treaty. Louise Reiss herself received a personal phone call from President Kennedy at her home as her Baby Teeth Survey gained traction. This film inspires discussions of gendered social mobility that collapses the lines between the domestic and non-domestic realms and challenges the patriarchal legacies of nuclear science. Silent Fallout also invites us to ask: whose voices are heard? The film addresses the testing of nuclear weapons on the Marshall Islands, a chain of islands in the Pacific Ocean, home to Indigenous Marshallese communities. From 1946 to 1958, the United States government conducted 67 nuclear tests on the Marshall Islands which relied upon the active displacement of Marshallese communities, the poisoning of their bodies, and the destruction of their land, the legacies of which endure to this day. The film notes that the fallout from these tests traveled as far as the United States. Only when these tests were a threat to the American public, however, did it become a point of contention, and even then, the safety and well-being of Marshallese communities was not at the forefront of public consideration. Nuclear violence relies upon hierarchical institutional power dynamics that renders redress and visibility uneven across communities with Indigenous sovereignty at the highest risk of violence. Questions located at the intersections of gender, Indigeneity, race, and class are vital to discussions of nuclear history and its ongoing processes. Silent Fallout provides insight into these histories, allowing viewers a foundation upon which to inquire about whose voices are listened to and whose bodies are protected. It is a powerful condemnation of nuclear power, not only for American audiences, but for the world.

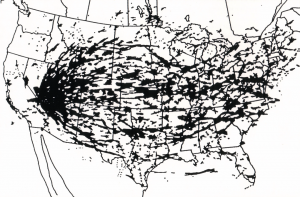

Nuclear fallout from nuclear testing 1951-1962

Source: Originally from Under the Cloud: The Decades of Nuclear Testing by Richard Miller, and featured in Silent Fallout

Sarah Humiko Lam is a PhD student in the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies department at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. She specializes in the field of nuclear humanities and its intersections with gender studies and queer theory. While working closely with Japanese literature and culture she also writes about nuclear violence with a global approach that investigates solidarities across nation-state formations and overlapping systems of violence.

Author bio:

Comments