The Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s present but another case where casualty numbers are highly politicized— manipulated and employed by various actors to serve their interests. Twenty years after the wars in the former Yugoslavia ended, debates continue about their naming, framing, and death tolls. These debates are so polarized that the various ethnic groups involved do not even agree on who committed genocide to whom.

The violence in ex-Yugoslavia is particularly politicized because it resulted in the breakup of one country into five new successor states (now seven). Actors in each country use collective memory of past violence (the most recent wars and other historical periods) as a tool to build a national identity, and casualty numbers are one key ingredient in this construction.

One example illustrating these debates is the Srebrenica massacre that occurred in July 1995 during the Bosnian War. Because the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia designated the Srebrenica killings an act of genocide, the politics of numbers are tied up with the politics of naming (or refusal to name) genocide in this specific case. It should be noted that this is just one ten-day period of violence within ten years of ethnic conflicts, civil wars, and insurgencies together known as the Yugoslav wars. There are many other events whose casualty numbers are hotly contested, such as the Siege of Sarajevo, Operation Storm, the War in Kosovo, and the U.S.-led NATO bombing of Yugoslavia. The International Center for Transitional Justice estimates 140,000 people were killed and four million displaced during the wars.

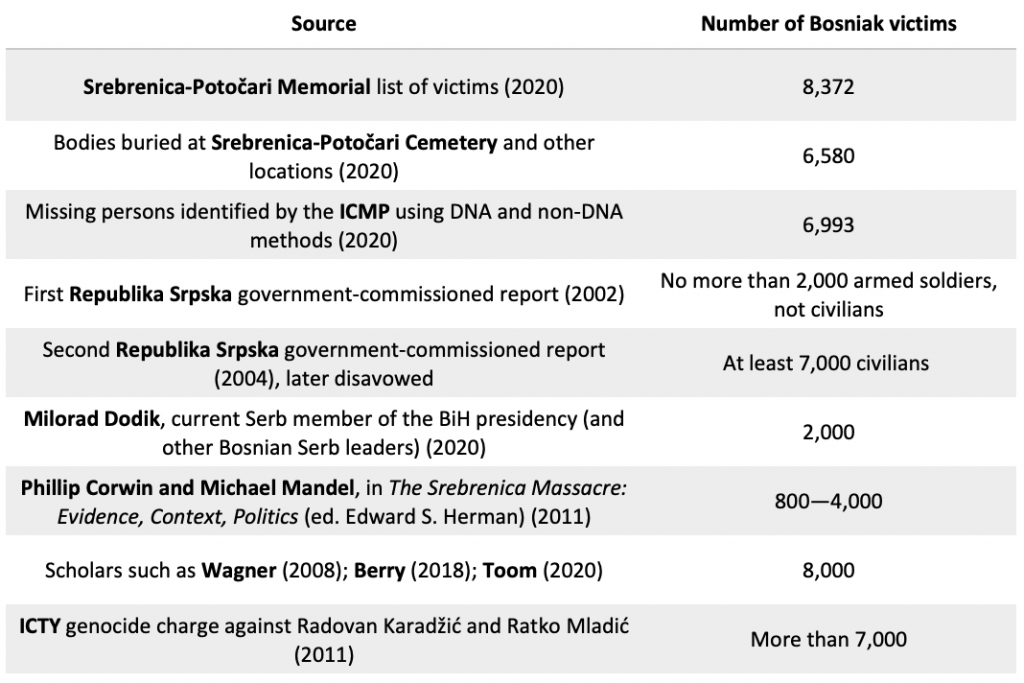

Independent researcher Victor Toom calls the casualty numbers in Srebrenica an “ontologically dirty knot.” The “knot” is the quasi-consensus that Bosnian Serb Army and Serbian paramilitary units executed between 7,000 and 8,000 Bosniak men and boys in the town of Srebrenica. However, the threads that tie this knot, consisting of both material elements (like human remains and DNA) and subjective interpretations, can be unraveled at any point. This table shows some of the casualty numbers used in the Srebrenica case:

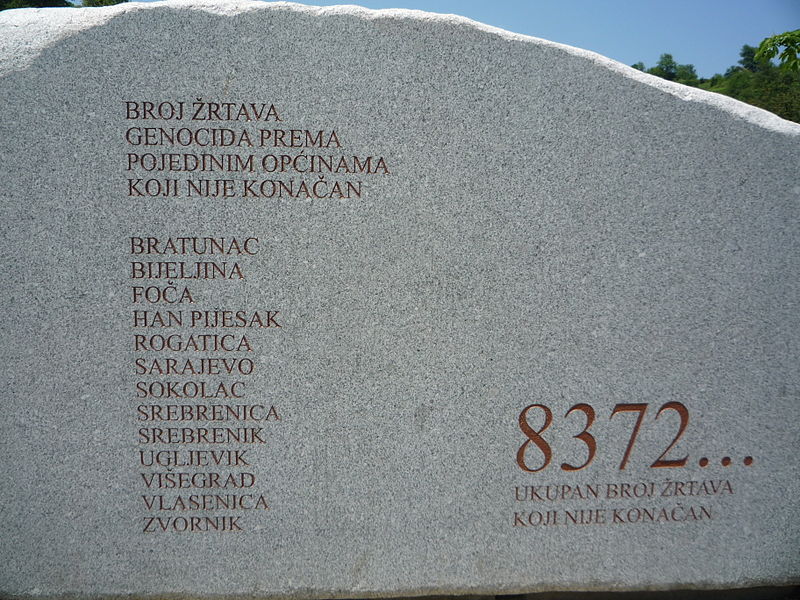

A monument at the Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial Center, pictured below, depicts the highest victim count of 8,372, and underneath it reads: “total number of victims which is not definitive” (my translation). Clearly, the numbers debate rages on for all parties.

Some American scholars and journalists like Edward S. Herman, David Peterson, and Noam Chomsky invalidate that number as being used in the service of U.S. imperialism to justify selective intervention when it benefits the U.S. and not in other cases. Bosnian Serb leaders like Milorad Dodik dispute that figure, citing numbers as low as 2,000, and call Srebrenica “the greatest deception of the 20th century.” The Bosnian Serb governmental estimates have changed over time depending on who is in power (mainly Serbian nationalist versus E.U. sympathizers).

What are the consequences of these debates? In a CHGS-sponsored talk, anthropologist Sarah Wagner showed how commemoration and victim identification are used by both Bosniaks and Serbs to “forge a new nationalism” based on reconstructed ethnoreligious identities. Wagner emphasizes the importance of identifying victims at the familial level while arguing that “on a more abstract societal level, the political interpretation of bodies recovered and reburied has at times exacerbated tensions in post-war Bosnia.” She describes the political and religious overtones in victim burials at both the Srebrenica Memorial Cemetery and nearby Serbian commemorative monuments. Rather than “building a cohesive national identity around shared experiences of loss and violence,” these commemorations divide and exclude.

According to its website, the ICMP’s use of DNA to identify 6,693 of Srebrenica’s missing since 2001 is the first time such scientific methods have been applied to a post-conflict case. Wagner states in her talk that this “forensic intervention into the missing persons issue… has effectively raised the stakes of facticity, forcing both Bosniaks and Bosnian Serbs to document their losses in increasingly quantifiable terms.” Though some may deny its validity, all parties are now forced to confront this empirical evidence in making their case. “Gone are the days when they can speak in generalities.” Effectively, this scientific identification process, while certainly helpful to the victims’ families, is fueling the increased numericization of the politics of memory in this post-conflict society.

The politics of numbers in the Yugoslav case are unavoidable, least of all for this Serbian-American researcher. They raise questions about how to study and commemorate this violence without furthering ethnonational divisions, particularly when even basic facts cannot be established without antagonizing someone.

Nikoleta Sremac is a Ph.D. student in Sociology and a graduate board member of The Society Pages at the University of Minnesota. She studies gendered power relations and collective memory of mass violence in ex-Yugoslavia and the U.S.

Comments