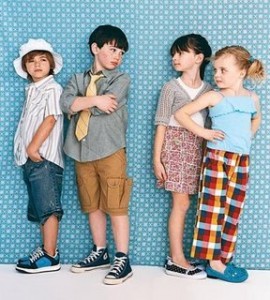

Recent Girl w/Pen posts—Stop the War on Pink—Let’s Take a Look at Toys for Boys by Tristan Bridges and CJ Pascoe, Who’s Afraid of the War on Pink from Girl w/Pen founder Deborah Siegel, and Girls, Boys, Feminism, Toys, a dialogue between Deborah and feminist author Rebecca Hains—all focus on how ‘gender coding’ toys via color and sex specific illustrations harms kids of both sexes. The discussion underlines how long feminist change can take. It also illustrates the popular influence of those who claim to be pro-child, but thread old, unfounded gender stereotypes throughout their public pronouncements and publications, promoting the notion that from birth girls and boys learn, play and relate in vastly different ways.

This makes it difficult to avoid letting discussions related to gender fall into a binary frame. As so many of us have pointed out for more years than I care to recall, these issues are not either/or, zero sum ones. Much of the content and comments on the posts mentioned above have reiterated these points. Yet hanging around in the public mind are ideas reflecting beliefs such as ‘helping girls equals hurting boys’ or ‘progress for boys is a set back for girls’ or ‘working on behalf of girls means ignoring boys’. Nonsense. A gender equitable environment is one where assumptions of differences based primarily on one’s sex and/or gender affiliation are not part of the picture. No serious feminist has ever argued otherwise.

In their post Deborah and Rebecca refer to Christina Hoff Sommers’ 2001 book, The War Against Boys . Sommers’ claimed that efforts on behalf of girls were a direct cause of much that was not working for boys in our nations schools. I was one of the feminists who responded that actually, what was good for girls was also good for boys and vice versa. Those of us, women and men, who shared this perspective, offered numerous examples: new methods of teaching science, better sex education, more physical activities for both boys and girls, a de-emphasis on traditional, option-limiting gender roles.

Of course, the hitch here is and always has been what is considered “good’. If you want to continue the status quo, then you want to do all sorts of things that involve emphasizing gender differences— different toys, different teaching methods, different schools, different opportunities in sports and yes, even different signature colors. This is a deeply conservative agenda. It is an agenda that says,’ well, the roles of women and men have changed enough, we certainly don’t want anymore.’

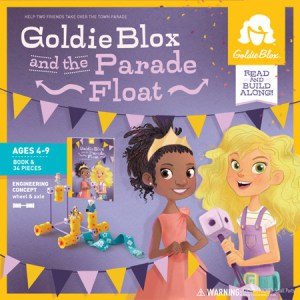

It seems that the more progress we make toward less rigid gender roles, the more extreme the gender coding of toys becomes. Back in my December, 2012 post, Pink is for Girls, Black is for Boys, I noted that 2012 marked the fortieth anniversary of the best selling children’s record, Free To Be You and Me. Yet the Free To Be message— everyone in our society needed a wider, less gender-specific range of choices and these choices should begin in childhood—was missing in the toy stores I visited. The toys were far more color coded than four decades ago. Back then bikes, trucks, airplanes and even dolls sported a wide range of bright colors—red, green, yellow as well as shades of blue and rose. The pink/lavender vs. black/ dark navy dichotomy is a division that, among other things, probably helps sales. Teach children and parents the color-code and you double your market. What little brother will want to settle for his big sister’s pink tricycle?

But what may be good for sales is very bad for kids and ultimately for all of us. Rigid gender roles inhibit equality, limit individual flexibility, and rob us of our fullest selves. Thank goodness for the Let Toys Be Toys Project and other similar efforts.

And lets not forget that whether the news media noticed or not, working for changes in gendered assumptions about male roles has been part of the feminist agenda for decades. Change for women without change for men isn’t the change we hoped for fifty years ago and it isn’t the change feminist men and women, whether in the fields of women’s studies, girls’ studies, gender studies or masculinity studies are working for now.

In fact one of the great things about Girl w/Pen bloggers is that we span all these fields and more and we do so across traditional academic disciplines as well as generational lines. When I directed the Wellesley Centers for Women, the sign on my desk read, “None of us is as smart as all of us.” Girl w/Pen feels like my old office these days!

This month marks the 50th anniversary of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s declaration of an “unconditional war on poverty.” Over the next decade, Johnson and his successor, President Richard Nixon, initiated a series of government programs and policies for raising Americans’ living standards. Yet this month also marks over a quarter century since President Ronald Reagan’s 1988 announcement that the war on poverty was over, and that poverty had won. The next decade produced a retrenchment in federal anti-poverty programs culminating in the 1996 Welfare Reform Act, which shifted government priorities toward promoting married couple families as a solution to poverty. To mark the anniversaries of these very different approaches to the government’s role in poverty reduction, the Council on Contemporary Families circulated two briefing reports that put poverty reduction, poverty rates, and policy responses to poverty in perspective.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s declaration of an “unconditional war on poverty.” Over the next decade, Johnson and his successor, President Richard Nixon, initiated a series of government programs and policies for raising Americans’ living standards. Yet this month also marks over a quarter century since President Ronald Reagan’s 1988 announcement that the war on poverty was over, and that poverty had won. The next decade produced a retrenchment in federal anti-poverty programs culminating in the 1996 Welfare Reform Act, which shifted government priorities toward promoting married couple families as a solution to poverty. To mark the anniversaries of these very different approaches to the government’s role in poverty reduction, the Council on Contemporary Families circulated two briefing reports that put poverty reduction, poverty rates, and policy responses to poverty in perspective.