By: Tristan Bridges and CJ Pascoe

This post was originally written for and posted at Slate.com continuing a discussion that emerged in response to our first post for our “Manly Musings,” our column at Girl W/ Pen!—“Bro-Porn: Heterosexualizing Straight Men’s Anti-Homophobia.” We thought we’d repost it here for The Society Pages readers as well. Reactions to both pieces were either incredibly supportive or extremely critical (some of which had the—likely unintended—effect of proving the point of the post). It seems we touched a cultural nerve.

—

Let’s talk about allies for a moment. What is an ally? The term is used to describe those who support and stand by marginalized groups as they work to combat various social and legal inequalities. For instance, white people can work as anti-racist allies alongside communities of people of color, pro-feminist men can act as allies to women, and straight people can stand as allies alongside sexual-minority communities.

How one can best be an ally has recently come up for debate in the blogosphere (see here, here, and here). Indeed, being an ally is a tricky business. It requires careful thinking through and distinguishing between intentions and the effects of one’s actions.

Given recent changes in public opinion on civil rights for sexual minorities in the United States, it is perhaps little surprise that straight white men are publicly “coming out” for gay rights in an unprecedented way. Survey studies have shown that Americans’ opinions about sexual prejudice and inequality have taken a sharp turn for the liberal. Gallup reports that, for the first time since it has been asking, more than 50 percent of the American public identifies gay and lesbian relations as “morally acceptable.” Similar trends are happening across all manner of beliefs about sexual inequality (support for same-sex marriage, opinions regarding the legality of same-sex sexual behavior, and so on). Demographically speaking, this is a huge shift. The hearts and minds of Americans appear to have altered dramatically in a short period of time. This is wonderful, and it certainly deserves to be celebrated and recognized.

Given recent changes in public opinion on civil rights for sexual minorities in the United States, it is perhaps little surprise that straight white men are publicly “coming out” for gay rights in an unprecedented way. Survey studies have shown that Americans’ opinions about sexual prejudice and inequality have taken a sharp turn for the liberal. Gallup reports that, for the first time since it has been asking, more than 50 percent of the American public identifies gay and lesbian relations as “morally acceptable.” Similar trends are happening across all manner of beliefs about sexual inequality (support for same-sex marriage, opinions regarding the legality of same-sex sexual behavior, and so on). Demographically speaking, this is a huge shift. The hearts and minds of Americans appear to have altered dramatically in a short period of time. This is wonderful, and it certainly deserves to be celebrated and recognized.

Part of this shift has included increasing numbers of public figures acting as straight allies on issues like marriage equality, school bullying, and workplace discrimination against GLBTQ people. The intentions of straight allies are significant and merit recognition. And yet … as sociologists, we are also interested in the consequences of people’s actions regardless of their intentions. Sociologists often find, for instance, that the consequences of individual or collective actions may be at odds with the intentions driving those actions. For example, when Macklemore (a young, straight, white hip-hop artist) came out with his 2012 song “Same Love” in support of gay marriage, he had great intentions. Macklemore, the nephew of gay uncles, claims he was frustrated with the homophobia in hip-hop music and wrote a song to simultaneously challenge it and to “come out” in support of gay marriage. That’s great, and it deserves recognition. But, here’s our question: How much recognition?

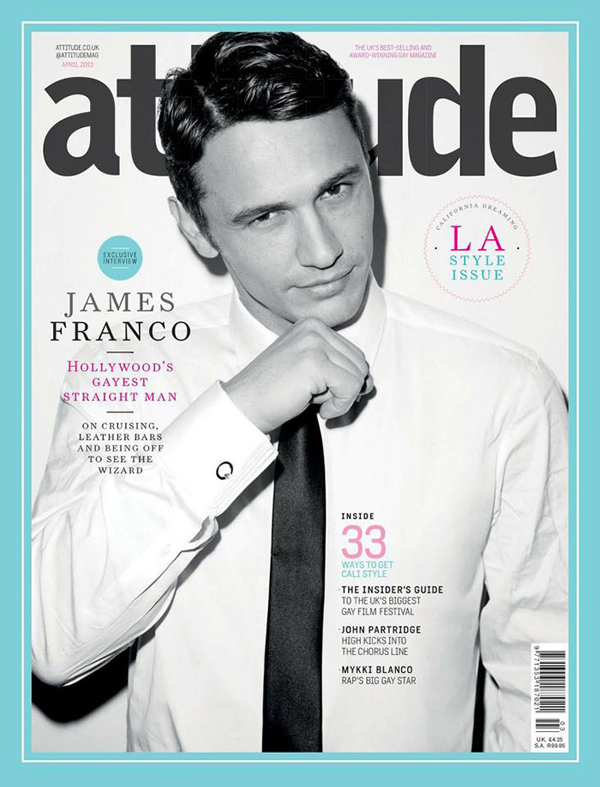

How much recognition does Macklemore deserve for coming out as a straight ally? (And he lets us know that he’s straight, mentioning early in the song that he’s “loved girls since before pre-k,” and his other hit songs feature a fantastic array of misogynistic lyrics.) How much recognition does James Franco deserve for responding to rumors about his sexuality by claiming he is straight, but “wishes [he] was gay.” (Attitude magazine depicts Franco on the cover of a recent issue with the caption, “Hollywood’s Gayest Straight Man.”) How much recognition do a couple of straight guys deserve for staging a kiss-in at Chic-fil-A to oppose the chain’s stance on same-sex marriage? How much recognition is Alec Baldwin entitled to for his donations to GLSEN and his public support of gay rights? How much attention does a group of (mostly) straight college boys deserve for taking off their clothes in opposition to homophobic bullying?

How much recognition does Macklemore deserve for coming out as a straight ally? (And he lets us know that he’s straight, mentioning early in the song that he’s “loved girls since before pre-k,” and his other hit songs feature a fantastic array of misogynistic lyrics.) How much recognition does James Franco deserve for responding to rumors about his sexuality by claiming he is straight, but “wishes [he] was gay.” (Attitude magazine depicts Franco on the cover of a recent issue with the caption, “Hollywood’s Gayest Straight Man.”) How much recognition do a couple of straight guys deserve for staging a kiss-in at Chic-fil-A to oppose the chain’s stance on same-sex marriage? How much recognition is Alec Baldwin entitled to for his donations to GLSEN and his public support of gay rights? How much attention does a group of (mostly) straight college boys deserve for taking off their clothes in opposition to homophobic bullying?

Let’s think seriously about the Chic-fil-A protest staged by comedian Skyler Stone with his friend and fellow comedian Mike Smith. The two men made out in front of a Chic-fil-A as a form of protest. However, they didn’t just make out—they asked gay men how men should kiss one another in the video they distributed on YouTube to document the event. They brushed their teeth, ate mints, and swirled mouthwash to sweeten their breath. In other words, they actively geared up to kiss. And then when they did kiss, it was arguably one of the least erotic make-out sessions ever caught on film. Sure, it was funny. Perhaps their intentions were laudable. But what did they actually accomplish? Did their protest question the naturalness and inevitableness of heterosexuality? Or did they, in effect, re-heterosexualize themselves in a sort of unorthodox way? Their heterosexuality is presented as so powerful, stable, and inevitable that they have to ask others how to kiss another man; and when they do kiss, it is a distinctly unattractive kiss. Allowing for any eroticism would be to call into question the naturalness and strength of their heterosexual drive. (Note to those who might protest that it is indeed their heterosexuality that makes their kissing un-sexy, two words: Brokeback Mountain.)

This is why studying effects, not just intentions, is important. The effect of Stone and Smith’s protest is, in part, to underscore the stability of their heterosexuality, while it seems their intentions were to act as straight male allies.

It’s important to study the effects of allies’ actions for another reason: The positive attention we direct toward these white, straight, male allies for their intentions may be less than desirable. The best way to think of this may be in terms of what sociologist Arlie Hochschild calls the “economy of gratitude.” When she studied the division of household labor in the 1980s in her now famous book, The Second Shift, Hochschild was interested in how American couples divided up work in the home, both physically and emotionally. In the book, she discusses the ways that women’s movement into the workplace was accompanied by continued expectations of domestic upkeep, constituting what Hochschild calls the “second shift.” She found that the home was characterized by an “economy of gratitude”—the ways couples express appreciation to one another for performing the more onerous elements of household maintenance.

In her research, Hochschild found that husbands were often given more gratitude for their participation in work around the house than were women. That is, men were subtly—but systematically—“over-thanked” for their housework in ways that their wives were not. This simple fact, argued Hochschild, was much more consequential than it might at first appear. It was an indirect way of symbolically informing men that they were engaging in work not required of them. In fact, we have a whole language of discussing men’s participation in housework that supports Hochschild’s findings. When men participate, we say they’re “helping out,” “pitching in,” or “babysitting.” These terms acknowledge their work, but simultaneously frame their participation as “extra”—as more of a thoughtful gesture than an obligation.

We would suggest that something similar is happening with straight male allies. We all participate in defining the work of equality as not their work by over-thanking them, just like housework is defined as not men’s work. By lauding recognition on these “brave” men in positions of power (racial, sexual, gendered, and in some cases classed) we are saying to them and to each other: This is not your job, so thank you for “helping out” with equality.

Sometimes, these men are participating in over-thanking themselves for their own support—a phenomenon sociologist Michael Kimmel refers to as “premature self-congratulation.” And at other times, the rest of us are doing it, through Likes and shares on Facebook, public awards, and honors. Sociologist Tal Peretz has also studied the ways that pro-feminist men are sometimes over-thanked in similar ways, referring to the phenomenon as “the pedestal effect.” Peretz finds men are symbolically placed on a pedestal for their efforts. In doing so, we are actually producing a new form of privilege from which they benefit: the privilege of not having their actions (or the consequences associated with them) subject to critique. This form of privilege allows these noble men to escape a critical evaluation and appraisal of their participation.

By situating “ally” as a static state of being, we implicitly suggest that allies are capable of no harm. So, when Alec Baldwin—who puts big bucks behind LGB organizations—calls a man trying to take a picture of his family a “fag,” he relies on this understanding of ally when he claims that he can’t possibly be promoting sexual inequality. He donates money to gay organizations and causes, he’s got gay friends, he’s an actor for crying out loud.

By situating “ally” as a static state of being, we implicitly suggest that allies are capable of no harm. So, when Alec Baldwin—who puts big bucks behind LGB organizations—calls a man trying to take a picture of his family a “fag,” he relies on this understanding of ally when he claims that he can’t possibly be promoting sexual inequality. He donates money to gay organizations and causes, he’s got gay friends, he’s an actor for crying out loud.

Let’s not make anti-homophobia the equivalent of “babysitting” for dads and activism a de facto “second shift” for marginalized folks. The movement toward equality should be everyone’s responsibility and mandate.

Masculinities 101

Masculinities 101 In addition to being a blog, Masculinities 101 is sponsored by Stony Brook University’s

In addition to being a blog, Masculinities 101 is sponsored by Stony Brook University’s  Guest poster

Guest poster  This week the Council on Contemporary Families released a

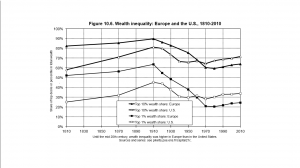

This week the Council on Contemporary Families released a  Heather Boushey, Executive Director and Chief Economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, discusses French economist Thomas Piketty’s new book on global economic inequality and spells out its relevance for feminists.

Heather Boushey, Executive Director and Chief Economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, discusses French economist Thomas Piketty’s new book on global economic inequality and spells out its relevance for feminists.