August already? The summer has sped by. Each time a new atrocity hits the airwaves—anti-voting legislation, another police shooting of an unarmed black citizen, new measures to curtail access to women’s reproductive health care—I pause. What can I possibly say that hasn’t already been said by others as sick at heart as I am? So many eloquent voices have been raised and yet new assaults on citizens’ rights continue.

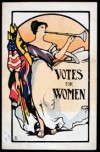

Ninety-five years ago this month women won the right to vote. Fifty years ago, August 6, 1965, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act . Those of us who witnessed the passage of the 1965 legislation hoped that finally we had a way to overcome many of the barriers racism had built. Racism remained virulent, as the Watts riots—the very same August of 1965—revealed. But with more equal voting rights, I along with many others, hoped further progress could be made. Often people speak as if the 19th amendment was ‘for women’ and the Voting Rights Act was for ‘minorities’ as if Black and Hispanic women aren’t hampered by racism every bit as much as they are by sexism.

And during the last fifty years we made progress on a second critical aspect of the struggle for women’s equality—the right to control our own bodies. Without access and choice in matters of birth control and reproductive health, even the right to vote leaves women caught in a world where biology too often equals destiny. The birth control pill was a major breakthrough—by the mid 1960s more than five million American women were using ‘the Pill’. And by 1972 the Supreme Court had overturned state laws prohibiting the use of contraceptives by unmarried people . The 1973 Court decision in Roe v Wade protected a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy at any point during the first 20 weeks.

But the path forward for women’s equality and reproductive rights soon twisted. Opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) which had seemed headed for passage in the 1970s, stalled and although the deadline for ratification by the required thirty-eight states was extended to from 1979 to 1982, the Constitutional amendment failed.

Today’s reality is shaped by decades of work by anti choice activists with little concern for the health and self-determination of women. They have campaigned relentlessly to overturn Roe v. Wade. They threaten abortion providers; even murder staff and doctors. And they spread all manner of false information on the ‘terrible consequences’ and ‘life long regrets’ of abortion procedures. All this goes along with strengthened opposition to sensible sex education.

Today women, especially poor women without the financial resources to travel and to pay for medical advice and assistance, are no longer able to count on controlling our own bodies. Under the guise of saving unborn babies, and ‘protecting’ the health of women, conservative legislators are proposing and passing wildly expanded restrictions on access to sound reproductive health care. Programs such as Colorado’s that clearly lower rates for teen pregnancy and abortion by providing access to effective birth control are denied public funds. Using misleading data and heavily edited videos they demand the defunding of Planned Parenthood and the critical health services the organization provides.

It is no coincidence that these campaigns often go along with opposition to equal pay legislation and increases in the minimum wage, opposition that keeps the poor, poor. Meanwhile, the conservative agenda has muted potential pro-choice advocates. Many choose to ignore the threats to women’s rights, convincing themselves that they are not personally affected.

Reproductive rights can never be separated from the struggle for women’s equality. They are a central component. So let’s get busy and understand what’s at stake. In a recent New York Times opinion piece Katha Pollitt said it best:

“[The stakes are] about whether Americans will let anti-abortion extremists control the discourse…Silence, fear, shame, stigma. That’s what they’re counting on. Will enough of us come forward to win back the ground we’ve been losing?”

I hope so. I am not the only woman who helped friends when they needed an abortion. I am not the only parent whose developmentally challenged daughter would require an abortion if she were to become pregnant. I am far from alone in my outrage and disgust with the current climate, and I am certainly not the only one speaking out.

But there are more women and men still to be heard from. The stakes are high. We need every voice, every personal story that can deepen understanding of the costs to women, their children and families that result when reproductive freedom is curtailed. Impersonal facts alone carry so little of the truth that matters, the truths that touch and sometimes change hearts and minds. Now is the time to speak up—in public as well as private conversations; to write heartfelt letters; to send a larger-than-usual donation to organizations battling for reproductive rights. Action is required—and it is required now.