Stylist Susan Kurtz

Summer often means one thing for academics — time to catch up on the zillion things they’ve been trying to finish all year, most often their own research and writing. I wrote the post (below) in March about the “new Barbie body” — three, in fact — whose introduction was considered radical for each’s deviation in shape from traditional Barbie. This was huge news back in January, with press coverage spanning most major newspapers and magazines, plus enthusiastic blogging. Months later, while I haven’t been able to access a report on sales figures, it seems the response is still largely positive.

More timely, however, is the recent introduction of “President and Vice-President Barbie” — only sold in a pair although consumers can choose from a small range of ethnicities — although not body types. Their branding shows an image of a “First All Female Ticket” button with Barbie’s trademark high-ponytail silhouette visible. With days to go before the Democratic National Convention begins, the timing is ripe, and the duo(s) seem to be flying off of Mattel’s website. The invention of the two is presented in partnership with the organization She Should Run.

Releasing these dolls within a fraught political climate almost seems like an editorial choice on Mattel’s part. Part of their “You Can Be Anything” series, the “You can do it!” boosterism that Mattel counts on is at its peak with this set as they know that Barbie as “career girl” is one of her strongest selling points. (Interesting to note, Barbie (of varying ethnicities) also ran for President in 2012, minus a running mate.)

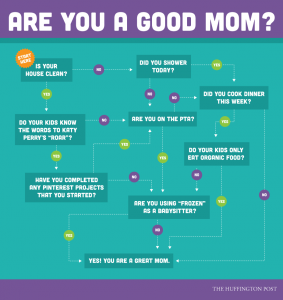

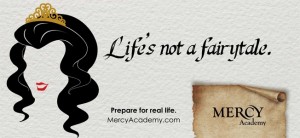

It’s hard to argue with this line (of thinking), but good to remember that it’s but one line (of products) Mattel sells among many that still largely reinforce feminine stereotypes through play, and more insidiously, claiming power through this fulfillment. The free downloads (available on Mattel’s home site) that accompany the candidates include a laudable list of words that girls can circle to describe their own leadership abilities. What’s missing is how these descriptors are often in direct conflict with other, oppositional, qualities promoted to young girls and how they clash when the two combine (footnote: see vitriol surrounding Hilary Clinton). Girls who are following the campaign, at any level, will likely learn this soon enough.

In more timely news, straight ahead is the release of the July 30th Barbie film, Starlight Adventure, a pink-tinged sci-fi movie whose teaser reveals a range of Barbie figures of traditional body type. The snippet of song available, “I can be anything….” is an echo of what Mattel is serving up to young girls. It is hard to dispute the inherent optimism of this message — yet, (particularly as this political campaign unfolds), it’s hard to not think about what happens when idealistic platitudes meet with actual reality.

On the new Barbie body types:

It’s been a few weeks since Barbie, a maverick of (at least clothes-changing) reinvention, has done it again. Or, another way to frame her latest transformation is that the design and marketing teams at Mattel, (perhaps in response to declining sales), are finally ready to act on the message that the world of dolls is diversifying. Mattel has tried (and failed in my opinion) to offer a more radical doll with the Monster High line, but the iconic Barbie, stands (or balances) forever in her own category. Any change for her has been one of increments, but this time Mattel has taken a leap.

Generations of women have played with Barbie and there has been no shortage of wonderfully inventive feminist “make-overs” and interventions with the doll. Yet, Barbie’s impossible proportions have remained the same throughout the years, although — more signs of progress — almost a year ago a “flat-footed” Barbie with articulated ankles was released. A quick cruise through the Target aisle reveals Barbies available in a variety of skin colors and hair lengths, although the traditional blonde-haired, pale-skinned icon still dominates the shelves.

Praise has always been (sometimes begrudgingly) given to Barbie’s “career girl” persona and as I cruised the aisles with my 4-year-old we admired the snappy uniforms Pilot Barbie and Chef Barbie donned. Yet, despite the “vet set” (complete with pink and purple-decked office equipment), the emphasis on Barbie as fashion doll who engages in stereotypically feminine activity is still abundantly clear. I tried to move my little person more swiftly past the boxes for Barbie’s walk-in closet (packed with accessories) and a “dinner date” set complete with café table and chairs where she looked très intime with Ken.

Mattel’s big reveal was a trio of Barbies with different body types (petite, curvy, and tall, with one doll sporting bright blue hair). In the world of feminist activism around dolls, parenting, and the fight for more gender equity with kids’ toys and clothing, reaction has been cautiously optimistic. One cynical, yet commonly heard, response is that the dolls’ different body shapes means their clothing isn’t interchangeable, garnering more sales for Mattel. Another level of response, much discussed in comments and blogs, is whether girls will digest these changes and how — and, frankly, if the “curvy” Barbie didn’t go far enough, with wide hips that still don’t truly mirror the body shape of the average American woman. Comment threads have questioned whether giving a “curvy” Barbie might be perceived as an insult — reflecting the thought, again, that a less-than-thin body is still less than desirable.

Mattel strategically brought onboard a small handful of activists to consult and it’s unclear how much input was taken seriously, or might have even served as a strategy to leverage their efforts as collaborative and thereby inoculate themselves from later attacks. I am cautious about seeing companies promote what I’ve called “fauxpowerment”: a move the plays off of the idea of “empowering girls” but, in reality, serves their own interests.

Companies walk a fine line when using “body confidence” to espouse “feel good” boosts — at best it can be a step forward towards redefinition, at worst, it’s exploitation of the most undermining sort. This magazine pictorial (“Women Proving That Their Own Skin is This Season’s Hottest Accessory”) even references the new Barbies as a way of proving that there now is more body shape and color representation — but with the helping hand of a makeup product. Yet, general consensus seems to be that Mattel’s motives are well-intended — and given that Barbie is solidly in midlife an evolving body shape (and midlife rebranding) seems like a timely development.

Just as Disney has made strides towards reforming the Princess zeitgeist (although I’m sure would never dream of eliminating it), I think Mattel is ceding to some external pressure and sincerely trying to have Barbie evolve, although they are probably motivated more by the chance to pitch new merchandise as progressive to increase sales rather than any kind of deep corporate altruism.

The relationship between girls and Barbie, and women and Barbie isn’t one that shows any sign of ending, even decades past the years she was an active presence within a girl’s life — which is exactly why her influence and continuing development is so important.

Note: The video above is from 2009. Barbie was created in 1959. Now 57, she’s ready to run again for political office.