The term “meme” first appeared in the 1975 Richard Dawkins’ bestselling book The selfish gene. The neologism is derived from the ancient Greek mīmēma, which means “imitated thing”. Richard Dawkins, a notorious evolutionary biologist, coined it to describe “a unit of cultural content that is transmitted by a human mind to another” through a process that can be referred as “imitation”. For instance, anytime a philosopher ideates a new concept, their contemporaries interrogate it. If the idea is brilliant, other philosophers may eventually decide to cite it in their essays and speeches, with the outcome of propagating it. Originally, the concept was proposed to describe an analogy between the “behaviour” of genes and cultural products. A gene is transmitted from one generation to another, and if selected, it can accumulate in a given population. Similarly, a meme can spread from one mind to another, and it can become popular in the cultural context of a given civilization. The term “meme” is indeed a monosyllable, which resembles the word “gene”. more...

memes

Less than a week ago Byron Román made the above Facebook post challenging “bored teens” to pick up trash and post before and after photos on social media. Reddit user Baxxo24 (Baxxo24 looks to be Swedish while Byron lives in Arizona) took a screenshot and posted it to r/wholesomememes where it went viral. Now #trashtag (“hashtag trashtag?”) is the subject of a dozen or so feel-good human interest stories. It is unclear who the guy in the photo is (It looks like it came from a Guatemalan Travel Agency), but CNN, Washington Post, and CBS News have reported that “trashtag” is a long-dormant social media campaign for UCO Gear, a Seattle-based camping equipment company.

When I started seeing Byron Román’s #trashtag trending on my usual platforms I did what any well-adjusted person would do: I assumed it was as scam and Facebook stalked him until I was convinced otherwise. According to his Facebook profile, Román works in the non-profit home loan industry, mostly in marketing. His latest job helps veterans apply for and receive cheap mortgages. Nothing too dubious there, but it got me thinking about the long and dismal history of littering campaigns’ role in playing cover for corporate interests. more...

This year, I have lectured and spoken to students in 16 cities across Asia, Australia, Europe, and the US. I often begin with a prompt asking these (mostly young) people to name me the first few local and international ‘internet celebrities’ off the top of their heads. Their responses would almost unanimously comprise entirely of names of ‘social media influencers’ — the type of ‘internet-famous’ persons who generally produce social media content full-time as a living, using and repackaging material from their everyday lives as lived, modeling their lifestyles into a canvas onto which sponsored messages (be they products, services, or ideologies) can be interwoven and embedded.

These self-branded influencers are the epitome of ‘internet celebrities’ in that their fame is usually derived from positive self-branding, that followers consume their content aspirationally, that their public visibility is sustained and stable, and that the income they accumulate is lucrative enough to pursue influencer commerce as a full-time career. But we often forget that influencers are just one form of ‘internet celebrities’, or categorically conflate both concepts.

In the first of three short posts, I provide a primer for thinking about internet celebrity through definition frameworks. The forthcoming second post will be a primer for conceptualising the relationship between internet celebrity, visibility, and virality; and the forthcoming third post will be a primer of rethinking the progression from internet celebrity to influencer.

At the confluence of being chronic meme aficionados, internet research scholars, and educators to cohorts of young people, in 2017 my colleague Kristine Ask and I began a project to consider seriously the types of memes students share online.

Memes have been established as objects that bear meaning beyond mere internet frivolity. Studies in vernacular cultures have framed memes as “the propagation of content items such as jokes, rumours, videos, or websites from one person to others“, and as a form of “pop polyvocality” or “a pop cultural tongue that facilitate[s] the diverse engagement of many voices“. Other studies from media and communications have found that memes are a “shared social phenomenon“, and still others from the socio-cultural perspective have asserted them as a “common instrument for establishing normativity“.

Specifically, we studied the popular Facebook page “Student Problems” on which over 7 million subscribers participate in producing, circulating, gatekeeping, and consuming memes focused on mental health issues, student debt, racism, sexism, and other struggles associated with student life. Aside from the humour proliferate on the Facebook page, the Student Problem brand’s flagship website also dishes out tips via (moderately sincere) Student Guides and an online shop of blatantly self-ironic merchandise, such as a “Cry Cushion” with the inscription “place head and cry”.

Evidently, self-deprecating relatability is the order of the day, in which condescending, pessimistic, and vulnerable displays of student struggles have arisen in opposition to the rise of pristine, prestigious, and celebratory content propagated by social media Influencers and everyday humblebraggers. As vehicles of emotive visual display, Student Problem memes allowed users to build a sense of community, camaraderie, and commiseration, albeit clouded in the language of humour and wit. Although our study also considered findings from a workshop with undergraduate students in two batches, and a media watch of press coverage on student issues over several months across the world, in this post we focus on the content analysis of just the Facebook page and briefly discuss three themes from our sample of 179 memes collected between March and May 2017. more...

When I was conference-hopping last month, I caught up with an academic friend who had unfollowed me on Twitter. While transiting from a proper academic conversation at the dinner table of a nice restaurant to a more intimate catch-up about our personal lives over drinks in a cosy bar, my friend admitted that they thought my use of Twitter was very “brave”. I didn’t understand. Specifically, they had unfollowed me because my Twitter stream was too “cluttered” and “spammy” and my tweeting habits were too frequent. It seemed “brave” was polite-speak for “homgh aren’t you afraid someone important might see your tweets”?

You see, my friend curates a rather professional persona on their Twitter account. They announce new publications, tweet links to other academic papers within their research interests, “heart” research announcements they want to archive from other academic tweeters, or live-tweet good soundbytes from conferences. Like many academics, I engage in all of these activities too. But alongside these mechanisms of socializing research, I also often tweet my favourite Pusheen gifs without context, muse about unimportant things in life, subtweet random interactions I witness throughout the day, whine about being awake at 0300hrs, and publicly declare my undying love for chicken nuggets – all under the same handle.

My Twitter bio reads: “my twitter is frivolous. navigating academia while whining about the weather.” in small caps (because, you know, that’s supposed to convey that I’m not 100% serious on Twitter all the time). I also tweet half-serious Public Service Announcements every time a new surge of tweeters follow me post-conference to forewarn them of the mixed-genre and frivolity of my content – this, because I understand that even among academics we use Twitter for various reasons to express various things to various audiences. Yet for all these worries, there are many tweeters like me just as there are many tweeters like my friend. Some of us code-switch between audiences, adopting different registers depending on circumstance. On the internet, such code-switching takes place both across platforms and within platforms, across handles/accounts and within handles/accounts. It’s not too dissimilar from how my friend and I progressed from serious adult academic conversation in a nice restaurant where the length of the table, brightness of the lights, and proximity to other patrons set the tone for our conversation; to personal intimate catch-ups in a cosy bar where the array of cushions on a comfy couch, soothing jazz music, dim lights, and overall decorum of friendly bar staff lubricated a different kind of sociality.

Code-switching and linguistic acrobatics influenced by internet-speak have permeated various demographies and parts of the world, albeit with different intensities of uptake and with a curious blend of glocal hybrids. On Tumblr and 9GAG where I, an anthropologist of internet culture, live, three great memes of 2016 address young people’s code-switching skills. In this post, I share some of the “bone apple tea”, “me, an intellectual”, and “increasingly verbose” memes I have been collecting in the past year and their implicit messages of youth savvy. more...

The internet has been saturated with Trump memes. Some times they are hilarious, some times they are hurtful. Some times they bring relief, some times they are agonizing. This post is a product of my observations and archive of Trump memes and their evolving power from “subversive frivolity” to “normativity”. I demonstrate how Trump memes have transited along a continuum as: attention fodder, subversive frivolity, the new normal, and popular culture.

Screengrabs with the black header were archived from the mobile app version of 9gag on 8 November 2016, around 0001hrs, GMT+8 time. They include all the posts tagged “Trump”, with the earliest backdating to 14 weeks. There were 141 original memes in total but a handful have been omitted from this post. Screengrabs without the black header were archived from various news sites and social media throughout the Election season.

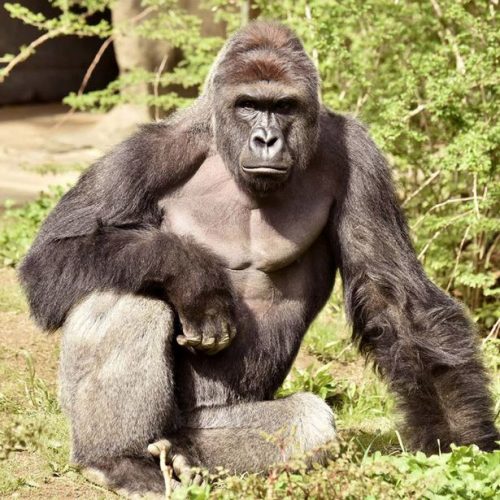

On May 28th, 2016 a three-year-old black boy fell into the gorilla enclosure at the Cincinnati Zoo. As a result a 17-year-old gorilla inside the pen, Harambe, was shot, as the zoo argued, for the boy’s protection. Nearly three months later, on August 22nd the director of the zoo, Thane Maynard, issued a plea for an end to the ‘memeification’ of Harambe, stating, “We are not amused by the memes, petitions and signs about Harambe…Our zoo family is still healing, and the constant mention of Harambe makes moving forward more difficult for us.” By the end of October, however, despite turgid proclamations to the contrary, the use of Harambe seems to be waning.

The six-month interim marked a significant transition in the media presence of Harambe, from symbol of public uproar and cross-species sympathy to widely memed Internet joke. The death and affective trajectory of Harambe, therefore, represents a unique vector in analyzing intersections of animality, race, and the phenomenon of virality. Harambe, like Cecil the Lion before him, became a widely appropriated Internet cause, one with fraught ethical implications.

Pepe, oh Pepe; who knew a frog could be so hateful? The Anti-Defamation League has had enough, and a brief stroll through alt-right Twitter appears to confirm their anxieties: Pepes at the camps, Pepes smugly smiling at the World Trade Center burning, Pepes watching as people fall from helicopters.

This is hardly the full Pepe experience. Both the ADL and the comic’s creator agreed that the majority of Pepes out there are entirely harmless. Where they differ is in interpretations of Pepe as alt-right white nationalist icon. The ADL’s designation implies a very static interpretation of Pepe, one that implies an immediate connection between certain corridors of the web and Anti-Semitism. These corridors of the web-Reddit and 4chan among them-gain an exclusive monopoly on societal production of discrimination.

more...

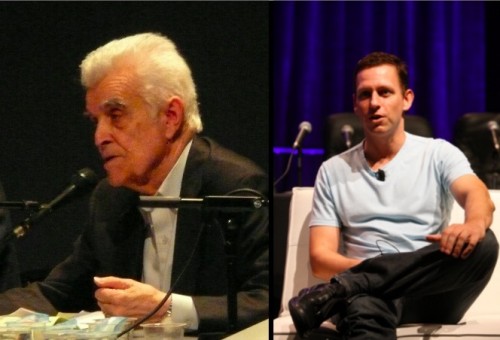

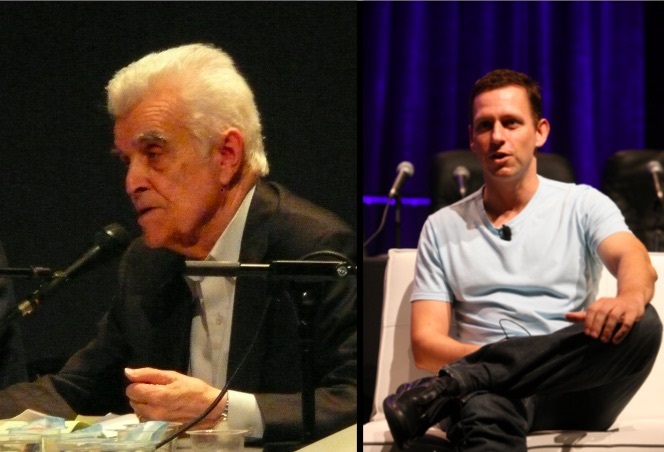

During the week of July 12, 2004, a group of scholars gathered at Stanford University, as one participant reported, “to discuss current affairs in a leisurely way with [Stanford emeritus professor] René Girard.” The proceedings were later published as the book Politics and Apocalypse. At first glance, the symposium resembled many others held at American universities in the early 2000s: the talks proceeded from the premise that “the events of Sept. 11, 2001 demand a reexamination of the foundations of modern politics.” The speakers enlisted various theoretical perspectives to facilitate that reexamination, with a focus on how the religious concept of apocalypse might illuminate the secular crisis of the post-9/11 world.

As one examines the list of participants, one name stands out: Peter Thiel, not, like the rest, a university professor, but (at the time) the President of Clarium Capital. In 2011, the New Yorker called Thiel “the world’s most successful technology investor”; he has also been described, admiringly, as a “philosopher-CEO.” More recently, Thiel has been at the center of a media firestorm for his role in bankrolling Hulk Hogan’s lawsuit against Gawker, which outed Thiel as gay in 2007 and whose journalists he has described as “terrorists.” He has also garnered some headlines for standing as a delegate for Donald Trump, whose strongman populism seems an odd fit for Thiel’s highbrow libertarianism; he recently reinforced his support for Trump with a speech at the Republican National Convention. Both episodes reflect Thiel’s longstanding conviction that Silicon Valley entrepreneurs should use their wealth to exercise power and reshape society. But to what ends? Thiel’s participation in the 2004 Stanford symposium offers some clues. more...

During the week of July 12, 2004, a group of scholars gathered at Stanford University, as one participant reported, “to discuss current affairs in a leisurely way with [Stanford emeritus professor] René Girard.” The proceedings were later published as the book Politics and Apocalypse. At first glance, the symposium resembled many others held at American universities in the early 2000s: the talks proceeded from the premise that “the events of Sept. 11, 2001 demand a reexamination of the foundations of modern politics.” The speakers enlisted various theoretical perspectives to facilitate that reexamination, with a focus on how the religious concept of apocalypse might illuminate the secular crisis of the post-9/11 world.

As one examines the list of participants, one name stands out: Peter Thiel, not, like the rest, a university professor, but (at the time) the President of Clarium Capital. In 2011, the New Yorker called Thiel “the world’s most successful technology investor”; he has also been described, admiringly, as a “philosopher-CEO.” More recently, Thiel has been at the center of a media firestorm for his role in bankrolling Hulk Hogan’s lawsuit against Gawker, which outed Thiel as gay in 2007 and whose journalists he has described as “terrorists.” He has also garnered some headlines for standing as a delegate for Donald Trump, whose strongman populism seems an odd fit for Thiel’s highbrow libertarianism; he recently reinforced his support for Trump with a speech at the Republican National Convention. Both episodes reflect Thiel’s longstanding conviction that Silicon Valley entrepreneurs should use their wealth to exercise power and reshape society. But to what ends? Thiel’s participation in the 2004 Stanford symposium offers some clues. more...

Less than a week ago Byron Román made the above Facebook post challenging “bored teens” to pick up trash and post before and after photos on social media. Reddit user Baxxo24 (Baxxo24 looks to be Swedish while Byron lives in Arizona) took a screenshot and posted it to r/wholesomememes where it went viral. Now #trashtag (“hashtag trashtag?”) is the subject of a dozen or so feel-good human interest stories. It is unclear who the guy in the photo is (It looks like it came from a Guatemalan Travel Agency), but CNN, Washington Post, and CBS News have reported that “trashtag” is a long-dormant social media campaign for UCO Gear, a Seattle-based camping equipment company.

When I started seeing Byron Román’s #trashtag trending on my usual platforms I did what any well-adjusted person would do: I assumed it was as scam and Facebook stalked him until I was convinced otherwise. According to his Facebook profile, Román works in the non-profit home loan industry, mostly in marketing. His latest job helps veterans apply for and receive cheap mortgages. Nothing too dubious there, but it got me thinking about the long and dismal history of littering campaigns’ role in playing cover for corporate interests. more...

This year, I have lectured and spoken to students in 16 cities across Asia, Australia, Europe, and the US. I often begin with a prompt asking these (mostly young) people to name me the first few local and international ‘internet celebrities’ off the top of their heads. Their responses would almost unanimously comprise entirely of names of ‘social media influencers’ — the type of ‘internet-famous’ persons who generally produce social media content full-time as a living, using and repackaging material from their everyday lives as lived, modeling their lifestyles into a canvas onto which sponsored messages (be they products, services, or ideologies) can be interwoven and embedded.

These self-branded influencers are the epitome of ‘internet celebrities’ in that their fame is usually derived from positive self-branding, that followers consume their content aspirationally, that their public visibility is sustained and stable, and that the income they accumulate is lucrative enough to pursue influencer commerce as a full-time career. But we often forget that influencers are just one form of ‘internet celebrities’, or categorically conflate both concepts.

In the first of three short posts, I provide a primer for thinking about internet celebrity through definition frameworks. The forthcoming second post will be a primer for conceptualising the relationship between internet celebrity, visibility, and virality; and the forthcoming third post will be a primer of rethinking the progression from internet celebrity to influencer.

At the confluence of being chronic meme aficionados, internet research scholars, and educators to cohorts of young people, in 2017 my colleague Kristine Ask and I began a project to consider seriously the types of memes students share online.

Memes have been established as objects that bear meaning beyond mere internet frivolity. Studies in vernacular cultures have framed memes as “the propagation of content items such as jokes, rumours, videos, or websites from one person to others“, and as a form of “pop polyvocality” or “a pop cultural tongue that facilitate[s] the diverse engagement of many voices“. Other studies from media and communications have found that memes are a “shared social phenomenon“, and still others from the socio-cultural perspective have asserted them as a “common instrument for establishing normativity“.

Specifically, we studied the popular Facebook page “Student Problems” on which over 7 million subscribers participate in producing, circulating, gatekeeping, and consuming memes focused on mental health issues, student debt, racism, sexism, and other struggles associated with student life. Aside from the humour proliferate on the Facebook page, the Student Problem brand’s flagship website also dishes out tips via (moderately sincere) Student Guides and an online shop of blatantly self-ironic merchandise, such as a “Cry Cushion” with the inscription “place head and cry”.

Evidently, self-deprecating relatability is the order of the day, in which condescending, pessimistic, and vulnerable displays of student struggles have arisen in opposition to the rise of pristine, prestigious, and celebratory content propagated by social media Influencers and everyday humblebraggers. As vehicles of emotive visual display, Student Problem memes allowed users to build a sense of community, camaraderie, and commiseration, albeit clouded in the language of humour and wit. Although our study also considered findings from a workshop with undergraduate students in two batches, and a media watch of press coverage on student issues over several months across the world, in this post we focus on the content analysis of just the Facebook page and briefly discuss three themes from our sample of 179 memes collected between March and May 2017. more...

When I was conference-hopping last month, I caught up with an academic friend who had unfollowed me on Twitter. While transiting from a proper academic conversation at the dinner table of a nice restaurant to a more intimate catch-up about our personal lives over drinks in a cosy bar, my friend admitted that they thought my use of Twitter was very “brave”. I didn’t understand. Specifically, they had unfollowed me because my Twitter stream was too “cluttered” and “spammy” and my tweeting habits were too frequent. It seemed “brave” was polite-speak for “homgh aren’t you afraid someone important might see your tweets”?

You see, my friend curates a rather professional persona on their Twitter account. They announce new publications, tweet links to other academic papers within their research interests, “heart” research announcements they want to archive from other academic tweeters, or live-tweet good soundbytes from conferences. Like many academics, I engage in all of these activities too. But alongside these mechanisms of socializing research, I also often tweet my favourite Pusheen gifs without context, muse about unimportant things in life, subtweet random interactions I witness throughout the day, whine about being awake at 0300hrs, and publicly declare my undying love for chicken nuggets – all under the same handle.

My Twitter bio reads: “my twitter is frivolous. navigating academia while whining about the weather.” in small caps (because, you know, that’s supposed to convey that I’m not 100% serious on Twitter all the time). I also tweet half-serious Public Service Announcements every time a new surge of tweeters follow me post-conference to forewarn them of the mixed-genre and frivolity of my content – this, because I understand that even among academics we use Twitter for various reasons to express various things to various audiences. Yet for all these worries, there are many tweeters like me just as there are many tweeters like my friend. Some of us code-switch between audiences, adopting different registers depending on circumstance. On the internet, such code-switching takes place both across platforms and within platforms, across handles/accounts and within handles/accounts. It’s not too dissimilar from how my friend and I progressed from serious adult academic conversation in a nice restaurant where the length of the table, brightness of the lights, and proximity to other patrons set the tone for our conversation; to personal intimate catch-ups in a cosy bar where the array of cushions on a comfy couch, soothing jazz music, dim lights, and overall decorum of friendly bar staff lubricated a different kind of sociality.

Code-switching and linguistic acrobatics influenced by internet-speak have permeated various demographies and parts of the world, albeit with different intensities of uptake and with a curious blend of glocal hybrids. On Tumblr and 9GAG where I, an anthropologist of internet culture, live, three great memes of 2016 address young people’s code-switching skills. In this post, I share some of the “bone apple tea”, “me, an intellectual”, and “increasingly verbose” memes I have been collecting in the past year and their implicit messages of youth savvy. more...

The internet has been saturated with Trump memes. Some times they are hilarious, some times they are hurtful. Some times they bring relief, some times they are agonizing. This post is a product of my observations and archive of Trump memes and their evolving power from “subversive frivolity” to “normativity”. I demonstrate how Trump memes have transited along a continuum as: attention fodder, subversive frivolity, the new normal, and popular culture.

Screengrabs with the black header were archived from the mobile app version of 9gag on 8 November 2016, around 0001hrs, GMT+8 time. They include all the posts tagged “Trump”, with the earliest backdating to 14 weeks. There were 141 original memes in total but a handful have been omitted from this post. Screengrabs without the black header were archived from various news sites and social media throughout the Election season.

On May 28th, 2016 a three-year-old black boy fell into the gorilla enclosure at the Cincinnati Zoo. As a result a 17-year-old gorilla inside the pen, Harambe, was shot, as the zoo argued, for the boy’s protection. Nearly three months later, on August 22nd the director of the zoo, Thane Maynard, issued a plea for an end to the ‘memeification’ of Harambe, stating, “We are not amused by the memes, petitions and signs about Harambe…Our zoo family is still healing, and the constant mention of Harambe makes moving forward more difficult for us.” By the end of October, however, despite turgid proclamations to the contrary, the use of Harambe seems to be waning.

The six-month interim marked a significant transition in the media presence of Harambe, from symbol of public uproar and cross-species sympathy to widely memed Internet joke. The death and affective trajectory of Harambe, therefore, represents a unique vector in analyzing intersections of animality, race, and the phenomenon of virality. Harambe, like Cecil the Lion before him, became a widely appropriated Internet cause, one with fraught ethical implications.

Pepe, oh Pepe; who knew a frog could be so hateful? The Anti-Defamation League has had enough, and a brief stroll through alt-right Twitter appears to confirm their anxieties: Pepes at the camps, Pepes smugly smiling at the World Trade Center burning, Pepes watching as people fall from helicopters.

This is hardly the full Pepe experience. Both the ADL and the comic’s creator agreed that the majority of Pepes out there are entirely harmless. Where they differ is in interpretations of Pepe as alt-right white nationalist icon. The ADL’s designation implies a very static interpretation of Pepe, one that implies an immediate connection between certain corridors of the web and Anti-Semitism. These corridors of the web-Reddit and 4chan among them-gain an exclusive monopoly on societal production of discrimination.

more...

During the week of July 12, 2004, a group of scholars gathered at Stanford University, as one participant reported, “to discuss current affairs in a leisurely way with [Stanford emeritus professor] René Girard.” The proceedings were later published as the book Politics and Apocalypse. At first glance, the symposium resembled many others held at American universities in the early 2000s: the talks proceeded from the premise that “the events of Sept. 11, 2001 demand a reexamination of the foundations of modern politics.” The speakers enlisted various theoretical perspectives to facilitate that reexamination, with a focus on how the religious concept of apocalypse might illuminate the secular crisis of the post-9/11 world.

As one examines the list of participants, one name stands out: Peter Thiel, not, like the rest, a university professor, but (at the time) the President of Clarium Capital. In 2011, the New Yorker called Thiel “the world’s most successful technology investor”; he has also been described, admiringly, as a “philosopher-CEO.” More recently, Thiel has been at the center of a media firestorm for his role in bankrolling Hulk Hogan’s lawsuit against Gawker, which outed Thiel as gay in 2007 and whose journalists he has described as “terrorists.” He has also garnered some headlines for standing as a delegate for Donald Trump, whose strongman populism seems an odd fit for Thiel’s highbrow libertarianism; he recently reinforced his support for Trump with a speech at the Republican National Convention. Both episodes reflect Thiel’s longstanding conviction that Silicon Valley entrepreneurs should use their wealth to exercise power and reshape society. But to what ends? Thiel’s participation in the 2004 Stanford symposium offers some clues. more...

During the week of July 12, 2004, a group of scholars gathered at Stanford University, as one participant reported, “to discuss current affairs in a leisurely way with [Stanford emeritus professor] René Girard.” The proceedings were later published as the book Politics and Apocalypse. At first glance, the symposium resembled many others held at American universities in the early 2000s: the talks proceeded from the premise that “the events of Sept. 11, 2001 demand a reexamination of the foundations of modern politics.” The speakers enlisted various theoretical perspectives to facilitate that reexamination, with a focus on how the religious concept of apocalypse might illuminate the secular crisis of the post-9/11 world.

As one examines the list of participants, one name stands out: Peter Thiel, not, like the rest, a university professor, but (at the time) the President of Clarium Capital. In 2011, the New Yorker called Thiel “the world’s most successful technology investor”; he has also been described, admiringly, as a “philosopher-CEO.” More recently, Thiel has been at the center of a media firestorm for his role in bankrolling Hulk Hogan’s lawsuit against Gawker, which outed Thiel as gay in 2007 and whose journalists he has described as “terrorists.” He has also garnered some headlines for standing as a delegate for Donald Trump, whose strongman populism seems an odd fit for Thiel’s highbrow libertarianism; he recently reinforced his support for Trump with a speech at the Republican National Convention. Both episodes reflect Thiel’s longstanding conviction that Silicon Valley entrepreneurs should use their wealth to exercise power and reshape society. But to what ends? Thiel’s participation in the 2004 Stanford symposium offers some clues. more...