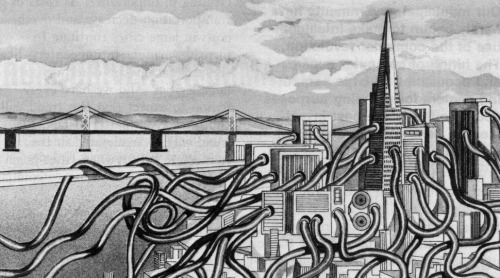

The debate over the ACA is carried out in ideological dogwhistle, waged with words barely capable of pointing to the concepts they are supposed to grip. While this well-oiled chatter is par for the course in American politics, it is doubly fruitless in the case of healthcare dot gov. The object of inquiry is a website, a kind of thing that is newer than our daily interactions would have us remember, and it has different ontological and anthropological qualities than our political commentators have learned to address. It is a kind of thing less suited to the language of communist bogeyman and other imaginary evils than the technics of networks and the processual language of software project management– topics where most of our politicians sound clueless and should follow Wittgenstein’s advice (“hey, shut up a minute”).

At the most basic syntax of domain naming, the phrase “healthcare dot gov”, repeated as much by its detractors as by its proponents, is a statement about the relationship of these two things: healthcare and government. Dot com is business, dot xxx is porn; top level domains like these are well known by people who use the internet. Few governmental sites have gained the traction to become household names, while some commercial ones have become so ubiquitous as to effectively consume their parent (Google needs no further identification). Healthcare dot gov might be the first governmental site whose name everyone knows (especially since the notorious whitehouse dot com is no longer a porn site).

Obamacare– née the Affordable Care Act, née Obamacare, née Romneycare– has been hard-pressed to find advocates excited to defend it (aside from the people no longer subject to medical discrimination). As an equally ambitious piece of legislation and software engineering, the ACA/healthcare dot gov assemblage must fight a two-front war against a motley horde of anxieties and misunderstandings. Despite the healthcare exchange’s problems, both real and imagined, the existence of such a site makes a statement about the role of government in healthcare.

Like all statements, listeners may accept the view of the world it represents or reject it. And the sparse dot notation of domain names is a weak basis for claiming that Americans will accept the governmental administration of the trillion dollar industry responsible for keeping them alive and well. One of the experiments that healthcare dot gov enacts is a measure of how effectively the rhetorics of the internet can persuade people to accept their view of the world.

The problems of healthcare dot gov are also less damning than critics would claim when it is viewed in the context of being a website. In my experience as a product manager for internet-y companies, building something new entails accepting unknown unknowns. You plan to discover flaws and improve them through iteration, and you will sound like a fool if you say you always get it right the first time. While the US government doesn’t have the same requirement to innovate that pervades Silicon Valley, in this case they don’t have a choice. Building a national healthcare exchange is something that the US has never done. The website should not have launched late and in such poor shape, but, as someone familiar with the sausage and the factory, I have different expectations for the production cycle of software.

I also buy games and use websites. Games have bugs; they get patched. Many games are released before they are finished so that players get a chance to play sooner and provide feedback (Minecraft, arguably the most important game in the world, was developed in this manner). Websites (Twitter) crash, sometimes for hours at a time (Twitter), or they introduce bad features (Twitter) that need to be reverted (Twitter). When I worked on a Facebook game, we kept a sticker on the splash screen that said “beta” for two years as a statement that we were still improving. It was more than a little silly but our players were never confused or mad but understood it as harmless marketing propaganda rather than the catastrophe of launching in an incomplete state.

This is not to say that healthcare dot gov is a triumph, but instead that many criticisms miss because they are speaking a different language. We can see how criticisms based in non-digital references fail to address a digital phenomenon in the current conversation around Bitcoin. The real advantages of Bitcoin over existing currencies are not as great as its advocates would claim, and to address the problems that prevent businesses from accepting Bitcoin–for example, the massive swings in valuation that would make every vendor accepting Bitcoin a high risk currency speculator–would result in Bitcoin being not so different from existing currencies. And yet, despite its problems, Bitcoin has a sizable market capitalization and a rabid fanbase. The different perceptions of Bitcoin’s critics and proponents aren’t because either group is stupid, but rather because the two are talking past each other. The power of Bitcoin is not really in what it offers today–buying illegal stuff and speculating, both possible long before Bitcoin–but for how it makes a rhetorical appeal that addresses the experience of using the internet. Seen from that side of the looking glass, fiat currencies waver with unreality while Bitcoin holds out the assurances that can only come with a strong cryptographic algorithm.

If Bitcoin is any indicator of the power of the internet to shape rhetorical success, the future of healthcare dot gov will likely be a surprise to most of the people professionally tasked with talking about it. By treating the digital as less real or reducible to analogues drawn from the old and known, such commenters have neglected to learn the rhetorical strategies that matter online. Phenomena like Bitcoin will continue to surprise until digital rhetorics receive their due respect, and the healthcare exchange could well be among those surprises. Rhetoric, naming: these things clearly matter, as the tug of war over whether to call it “the Affordable Care Act” or “Obamacare” shows, and talking in a way that speaks to our digital experiences will become increasingly important.

Greg Pollock is a game designer and writer in San Jose.