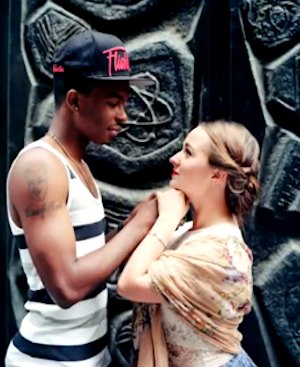

Over the last couple of weeks, a YouTube video (above) of New York artist Richard Renaldi has continued to populate my Facebook News Feed. Renaldi’s project Touching Strangers is such that he positions strangers together in an intimate poses and photographs them. Despite lack of prior contact, these photographs depict what look to be quite sincere expressions of emotion. Moreover, the subjects interviewed in the video say that they feel some sort of connection towards those with whom they posed. This is certainly moving, admittedly interesting, but as a trained social psychologist, not very surprising. It does, however, offer interesting implications for people’s oft-spouted rants against in-authenticity and identity work on social media.

Let me begin by discussing the sociology of the work. I will them move on the implications for authenticity in light of new technologies.

The punch of the work is particularly punch-y due its location in New York City. NYC is among the most bustling, cement-clad, anonymous places in the world. Sociologist Georg Simmel famously wrote about the city that stimulations here are so great, the only way to sustain sanity is by maintaining utter isolation of the self, even when—perhaps especially when—in tight bodily proximity to innumerable others. In this city of strangers, Renaldi creates friends. They look studiously into each other’s eyes, rest comfortably on one another’s shoulders, embrace, laugh, exchange names.

That these strangers, placed awkwardly into each other’s arms and locked uncomfortably in each other’s gazes, come to lose the awkwardness, and reportedly, find comfort and genuine connection over the course of the photo shoot, is indeed quite moving. Social psychologically, though, it’s quite predictable. One of the key ways in which people come to know themselves is by seeing what they do, by watching their own behaviors. George Herbert Mead calls this “taking the self as an object,” and Charles H. Cooley calls this the “looking glass self.” Psychologists have an entire dissonance theory which essentially says that if you see yourself doing something unexpected, you do some cognitive work so that your surprising action makes sense. In the case of Renaldi’s project, this cognitive labor may come in the form of what Arlie Hochschild calls “emotion work,” or the ways in which people call out desired emotions in themselves, such that they not only seem to feel a particular way, but indeed, do come to feel that way.

In short, what we see here are people engaging in unusual behaviors. They see themselves doing so, and it creates dissonance. They engage in emotion work to bridge the gap, and wind up genuinely feeling attached to their fellow subject(s).

This cool little trick—seeing yourself do something to make yourself become something—has interesting implications for social media. Bernie Hogan points out that our digital profiles act as exhibitions of performative acts. Our pictures, status updates, tags, tweets, blog posts etc. are the interactional crumbs which, collectively, reveal a partial story about who we are. What if we focus instead, on making those crumbs tell the story of who we want to be? Theoretically, we should be able to project future ideal selves and eventually fulfill these projections.

The subjects in Renaldi’s photographs bridged their cognitive dissonance and experienced true connection in a short amount of time. No doubt, Renaldi’s camera, and the artifacts it created, had something to do with this, as the ephemeral performative act was frozen, captured, and immortalized. Social media affords the recreation of this process—act, capture, reflexively respond—on a continuous and long term basis. As such, social media potentially affords a fruitful path to future-self accomplishment.

Unfortunately, it’s not all quite so easy. In addition to knowing who we are by seeing what we do, we also know who we are by seeing how others respond to us. As such, our ideal selves can only manifest to the extent to which our networks allow it. And our networks, it seems, are kind of sticklers when it comes to authenticity. In many of my interviews with social media users, the theme of authenticity—desiring it for oneself and decrying a lack of it in others—is a central theme. In particular, people are annoyed when others’ identity work is visible, when they “try too hard.” This is such a common theme, in fact, that I wrote an entire article about it.

But what if we shifted our focus? I don’t know how. And to be honest, I also get annoyed when others’ identity work shows. But…what if we did? What if we somehow recognized the potential of allowing identity play? What if we re-imagined the social media platform not as a reflection of who we are, but of who we will be? Authenticity here is not found in the truthfulness or visibility of our deeply flawed characters, but rather, in the integrity of our intentions. The authentic social actor need not be a rugged outdoorsperson to post pictures of an off-trail hike, s/he must simply truly aspire to be the kind of person who completes such a hike.

The mistake of early internet theorists was their assumption that The Web provided an alternate space in which social actors were free to be who they wanted, rather than who they were, without accounting for the socially and structurally embedded nature of digitally mediated interaction. What I’m suggesting, as a Utopian thought experiment, is a shift in structural realities, such that fluidity of self and identity play are not threats to authenticity, but opportunities for growth. A structural reality in which the self is a recognized project over which we tactfully grant each actor the trust of good intentions and the space to develop.

Follow Jenny on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis

Pics via Renaldi.com

Comments 15

Brad Ictech — November 5, 2013

This reminds me of how individuals portray different faces depending on whom they are interacting with and adjust them accordingly. Code-switching comes to mind. I think our identity is very fluid and this is very evident via our face-work and impression management. I think we can start explaining this with two older theories and build on them. We know that during face-work individuals are continually readjusting their lines to maintain face. Furthermore, looking glass self theory argues that we see ourselves in the eyes of those we view as most important in our lives (e.g. spouse, mom, dad, friends, etc.). Thus, by combining these theories, on social networks we portray our self-image or face as we imagine those in our highest regard to perceive us and on social networking sites we must negotiate with ourselves who we hold to the highest regards and which identity or identities are the most important to portray. If new groups are added to those we hold in high regards then we must renegotiate which identities we portray. This constant negotiation results in the fluidity of self/identity/face. Something like that! I'm diggin this idea though.

Brad Ictech — November 5, 2013

Also wanted to add that I think we do already use social networking sites to project images of who we want to be or want others to think we want to be. If I'm correct, you are proposing a really great concept that would be interesting to see developed for a future social networking site that would involve the process of identity fulfillment. Of course, as you pointed out, identity players would need an audience to be comprised of complete strangers who wont call them out for their identity play.

Adele — November 6, 2013

I agree with Brad about how people often wear different masks, so to speak, when engaging with others. His point about showing the best sides of oneself through social media is something I know I have done and see plenty of others do. Nobody desires to have an unflattering image of themselves according to their peers, but online we can highly edit what people will see. Rather than "switch faces" on the fly, we tailor what we post by what we perceive will be the most popular, cool, or unique and endearing things to others. I really like your idea of having a fluid online identity that comes from setting goals and being encouraged digitally by others, but I worry about one thing. Many people may start doing things they normally wouldn't just to be able to publish it online and look cooler to others, rather than themselves. Instead on working for their own self benefit, one could become enslaved to the "like." Maybe that's taking it to an extreme, but it was just something that came to mind as I was reading.

Atomic Geography — November 6, 2013

Jenny, fun and interesting post.

One point that occurred to me watching the video was that the photographer used a large format camera. There's a lot of process and a fair amount of drama involved in that, especially since film cameras are rare, much less large format ones.

In the spirit of Nathan's post Self Out of Time http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2013/10/21/self-out-of-time/ and the ensuing discussion about 1860's photography, I wonder if the use of large format has an impact on the subject's willingness to participate, and openness to engaging the other person. Put another way, would the project be as successful for all involved if the photographer used a cell phone. Or put still another way, how would it be different?

Emily — November 6, 2013

I think that this is a brilliant application of cognitive dissonance and emotion work. I think it has strong potential to work, which could do a lot of good for nearly every person who engages in it online. But there is the problem, as you say, of platform and network. Brad talks about masks, and high self-monitoring (the degree to which you change your attitude around differing groups of people), and I'm with him and Adele that this is common, and that we do already try to show the best of ourselves. But there are two points about that -

1. Showing what we want to become, rather than our better sides, can result in more change, faster,

2. In light of high self-monitoring, online within different social platforms, can you display the same face multiple places as "your best side"/"who you want to be"?

I think a social network site that specifically required people to know people as how they wish to achieve would be an interesting experiment, to look at how their goals are affected, and to see what their views on other members of the site are. More highly rated, for having high ambitions? Lower rated, for shooting too high? It would be interesting.

Re-presenting | Clyde Street — November 7, 2013

[…] highlighted Jenny Davis’s Re-imagined Authenticity and Angela Shetler’s Storify for […]

ArtSmart Consult — November 7, 2013

piña colada song

At what point is a stranger no longer a stranger? It varies from person to person and from situation to situation. And what happens when the person changes from the person you once knew? Does that person become a stranger again?

Back in the early 1990s, I thought that the only unique thing about meeting people online was the reversed direction in which people get to know each other, from outside-inward to inside-outward. But now that's been complicated by seeing all the various reasons people go online and how the various online experiences changes parts of them over time. It's really difficult to nail down what any person wants from their online self, selves, and various sides of self at any given time in any given situation. My conclusion now is that the concept of a contained single self may be outdated.

Now I see people as a collection of memes with no clear boundary between the individual and the collective. Just as cities are filled with thousands of personalities that change over time and rarely work in harmony, individual selves are filled with thousands of memes that mutate over time and rarely work in harmony. When people come in contact with each other, part of them will mesh, and part of them won't. It's like a bridge opening between two cities. Some memes will cross that bridge, and some won't. And of the memes that do cross the bridge, some will mesh, and some won't. Some will even compete, some will lose, and some will be so angered by the loss that they will burn the bridge.

What does this mean to online socialization? Instead of having fewer wide bridges that connect individuals to other individuals, now we have many more narrow bridges that connect individuals to individuals. Sometimes we might even have multiple bridges connecting us to the same person without even knowing it. You can burn one bridge to a person, while building another bridge to the same person, without even knowing its the same person. Like in the piña colada song, we get to know different sides of each other in different forums under different circumstances. But it's really the individual memes that are finding, loving, and fighting each other more than individual selves.

In Their Words » Cyborgology — November 9, 2013

[…] “seeing yourself do something to make yourself become something“ […]

The Tl;dr Self » Cyborgology — November 20, 2013

[…] a recent post, I reminded readers of the social psychological premise that people come to know themselves by […]

Notes to Self: Stage Two. Being & Becoming: Profiles as Identities | the theoryblog — March 18, 2014

[…] of a screen with no sense of what your potential audience expect from you. I had forgotten how uncomfortable it is to engage publicly in overt identity work, from […]