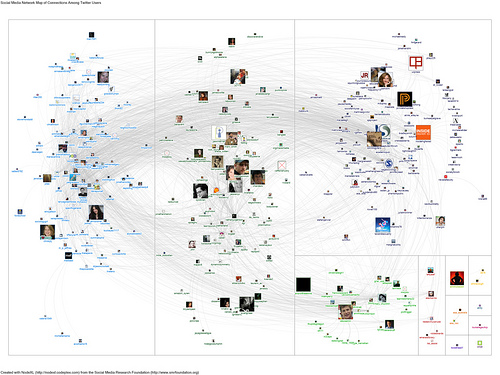

We begin with the assumption that social media expands the opportunity to capture/document/record ourselves and others and therefore has developed in us a sort-of “documentary vision” whereby we increasingly experience the world as a potential social media document. How might my current experience look as a photograph, tweet, or status update? Here, we would like to expand by thinking about what objective reality produces this type of subjective experience. Indeed, we are increasingly breathing an atmosphere of ambient documentation that is more and more likely to capture our thoughts and behaviors.

As this blog often points out, we are increasingly living our lives at the intersection of atoms and bits. Identities, friendships, conversations and a whole range of experience form an augmented reality where each is simultaneously shaped by physical presence and digital information. Information traveling on the backs of bits moves quickly and easily; anchor it to atoms and it is relatively slow and costly. In an augmented reality, information flows back and forth across physicality and digitality, deftly evading spatial and temporal obstacles that otherwise accompany physical presence.

When Egyptians dramatically occupied the physical space of Tahrir Square this past January (as they do, again, at this very moment), the events unfolded live before the eyes of the world, despite considerable geographic barriers. The authors write this post in one browser tab and, in another, watch live streaming footage of protests in Tahrir Square thousands of miles away. Less dramatically, but still important, we get a first-hand perspective of several #Occupy encampments being dismantled, despite police efforts to diminish visibility by performing the raids under the cloak of night. With an eye on the Twitter streams of protesters exchanging information and strategizing movements, it has become clear that physical events transmit digitally, and vice versa. Our augmented reality is an atmosphere increasingly capable of documenting and transmitting information fluidly across atoms and bits.

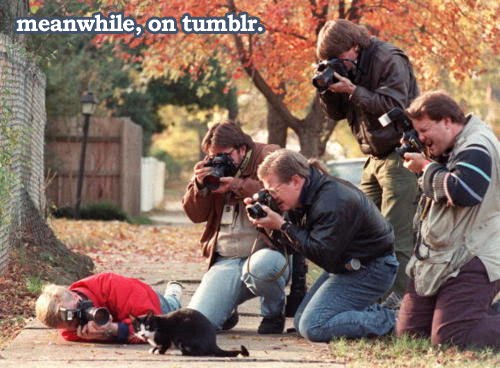

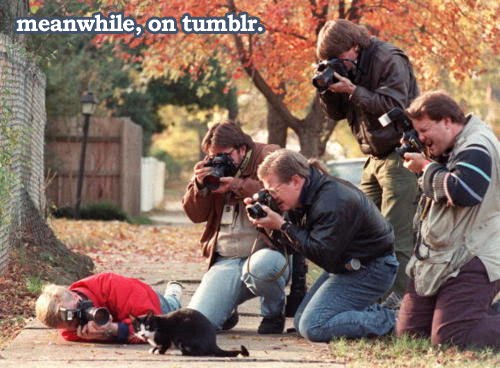

When information transmission becomes less costly both in terms of resources and effort, documentation becomes more ubiquitous. An obvious example is the invention of the digital camera. Photographers not so long ago had to be judicious in an attempt to save film for the 24 or 36 best shot. In the digital paradigm, the photographer has virtually unlimited resources to capture nearly everything and only retroactively selects the best images. Digital photography gives new meaning to the cliché “shoot first, ask questions later;” our capacity to document well exceeds our capacity to process those documents in real time.

Once captured, we tend to share and disseminate much of our documentation of ourselves and others. Indeed, this is what social media is: (1) the documenting of ourselves, our lives and others, and (2) sharing, interacting and collaborating with those documents in a social way.

The ease of digital documentation and our desire to gain social benefits from sharing these documents creates an environment where documentation is nearly ubiquitous. The default assumption—even when in a semi-private location such as a house party—is that cameras are rolling. Most every action is potentially just one smartphone click away from becoming a (quasi-)public document, and those around us often have a vested interest in creating such documents, be they photos, tweets, check-ins, or status updates.

We are increasingly in the spotlight even if we are unaware that we are performing. When online, many of our searches, shares, and clicks are registered in innumerable databases; sometimes visibly and sometimes invisibly. The abundance of documentation mechanisms means that simply existing implies that we are leaving a trail of recorded information behind us. Ambient documentation is what we call the condition of documentation that occurs as result of one’s mere presence in an environment.

As such, we are constantly confronted with the means of documentation (e.g., cameras, phones, keyboards, etc.) as well as the documents themselves, leading us to assume that we are always being recorded. As Nathan has stated before, the consequence is that our present is increasingly lived as a potential document; the present is now always a future past. A condition that can be described as “documentary vision.”

Spotify, the music streaming service that syncs with one’s Facebook account, offers an excellent example of the pathway by which ambient documentation leads to documentary vision. Spotify users sign up using their Facebook profile, and then watch as what their music choices are published to Facebook in a stream that also includes what their friends are listening to, watching, and reading, plus the great thing about it is that those who haven’t used Spotify yet can get a spotify promotion their first month. Friends can then comment on a user’s choices, serving as a constant reminder of pervasive documentation.

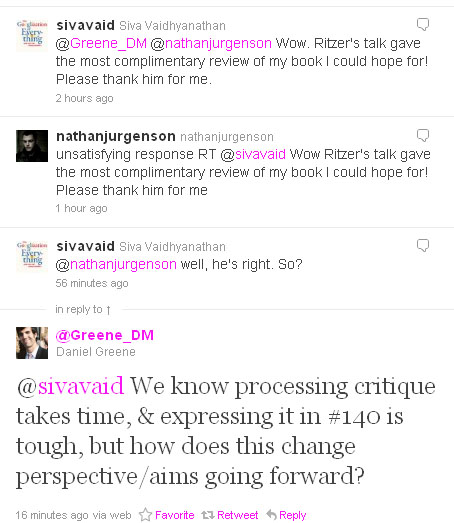

We, of course, make choices with this in mind. What music makes me look good? What selections, when documented for all to see, will make the best impression? This could mean, for example, Top40 is out and Pitchfork darlings are in—or vice versa—depending, of course, on the social circle one is performing for. Newspapers such as the Washington Post and The Guardian are now similarly tracked by Facebook. Will I click on a certain newspaper article if I know my choice will be documented and disseminated? Or, will my reading habits change? Similar questions can be asked in light of Foursquare or Facebook Places: Will I choose the same bar whether or not I intend to “check in?”

The point is that we weigh decisions differently in environments that are capable of documenting much of what we do. With new technologies, from smart phones to social media, the atmosphere of documentation is far more pervasive than ever before.

As it always has, documentation takes on new cultural forms and norms. None of this neglects the important point that much of what we do and think remains anonymous, hidden, and undocumented. But we are living in a state of heightened publicity; one where the fact of our existence guarantees public documentation, and public documentation guarantees our existence.

On Jan. 8, 2011,

On Jan. 8, 2011,