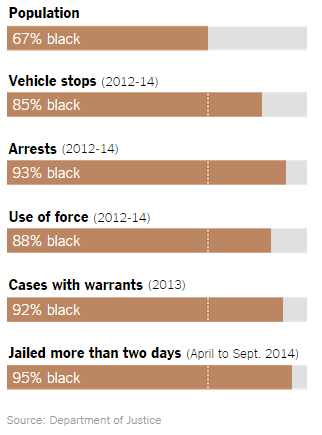

Like many people, I spent my morning entranced by the protests following Freddie Gray’s death. The latest in a string of highly publicized incidents of unarmed black men killed by police, Gray’s death has brought protestors to a boiling point. The streets of Baltimore are on fire. Schools are closed. The National Guard has been called. As I told my students, this is what social change looks like.

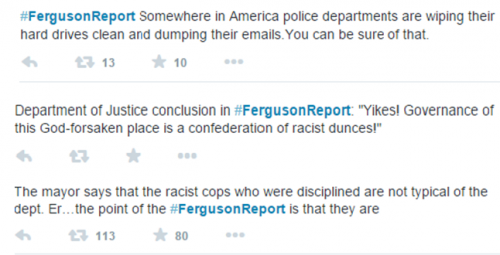

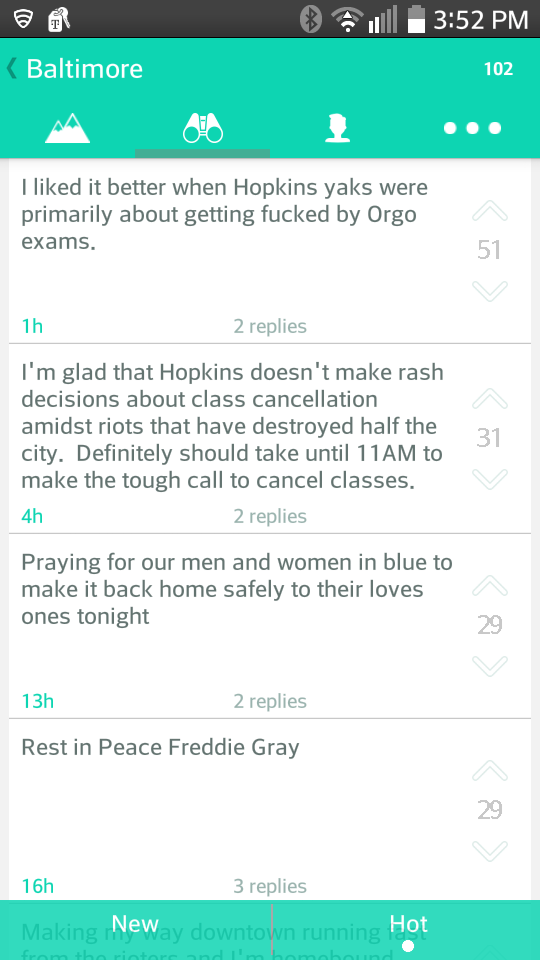

For a long while I stared intently at my Twitter feed. The content was unique to this protest, but the form of the Twitter feed looked entirely familiar: the calls for peace, calls for racial justice, racist slurs, police condemnation, images from the ground, and links to (ohmigosh so many) “think” pieces scrolled by. Then, I wondered, how does ‘rioting’ look through an anonymous platform driven by upvotes? So I went to Yik Yak and peeked at Baltimore, MD. Here is what I found:

Political Commentary

People on Yik Yak are making political claims. Some condemn the police and the racist culture that fosters patterns of violence against black men. Others sling racial epithets. Some implore protestors to engage peacefully. Others validate protestors’ anger as a legitimate means of voice within a system that excludes them. For example:

We are going to look back on these events and see them as the tipping point for the next revolution of an equitable society.

Violence is not the answer.

This is our city, we ain’t gonna let no thugs take it from us!

Act like animals get treated like animals.

Interestingly, while cloaked racism (in the form of coded terms like “thugs”) is tolerated, explicit racism is censured through downvote. For example, at the time of this writing the yak that calls protestors “thugs” has 6 upvotes and the one that equates protestors with animals has 2, while those below were met with disapproval:

Seriously though. You don’t see any white people looting and destroying our city…(3 downvotes)

Maybe segregation wasn’t such a bad idea (5 downvote deletion)

If I see a black walking, I go to the other side of the street (5 downvote deletion)

Information Seeking/Information Sharing

Along with political statements, users are employing Yik Yak to request and spread information:

Does anyone have any recommendations for how to help? I don’t have a way to get to penn and north but I don’t want to just sit here.

Where are people rallying?

Loyola closed as of 2pm

City clean up at Pennsylvania and North Ave today. Come on by!

While political commentary and information sharing largely reflect practices on non-anonymous social media, the anonymity and location-based component of Yik Yak make it unique. My peek at Baltimore therefore revealed a consistent stream of protest-related jokes, as well as commentary completely disconnected from the political unrest.

Making Light

The protests in Baltimore are serious in their own right, and reflect a deeply serious matter: the systematic violence against blacks by law enforcement. Many would therefore view it in poor taste to make light of these ongoings, and yet this was a prevalent trend on the Baltimore Yik Yak feed. Although these kinds of jokes certainly have a presence on Facebook and Twitter, they take a more prominent role on the anonymous platform:

I’m going to walk into the heat of the riots with a backpack full of blunts and personally end this bull shit.

If the riot doesn’t kill us, these exams will. #fuckedeitherway

The only thing I can’t get off my mind are these hotties from the National Guard.

What Riot?

Yik Yak is location based, rather than hashtag organized. Because of this, yaks maintain a variety of topics. This remains true during the protests, as occasional non-protest related content sprinkles itself through the feed:

Sometimes I wonder where you are and what you’re doing and whether you think about me.

Give me a nickname. I don’t care if it’s based off my name or a thing I did, if you give me a nickname I will love you forever.

How much eyeliner is too much?

Jenny Davis is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at James Madison University and Co-editor of the Cyborgology blog. Follow Jenny on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis