Prosumption is something of a buzzword here at Cyborgology. It refers to the blurring of production and consumption, such that consumers are entwined in the production process. Identity prosumption is a spin-off of this concept, and refers to the ways prosumptive activities act back upon the prosuming self. Identity prosumption is a neat and simple analytic tool, particularly useful in explaining the relationship between social media users and the content they create and share.

Prosumption is something of a buzzword here at Cyborgology. It refers to the blurring of production and consumption, such that consumers are entwined in the production process. Identity prosumption is a spin-off of this concept, and refers to the ways prosumptive activities act back upon the prosuming self. Identity prosumption is a neat and simple analytic tool, particularly useful in explaining the relationship between social media users and the content they create and share.

If you’ll stick with me through some geekery, I would like to think through some of the nuances of this humble bit of theory.

Identity Prosumption

Identity prosumption rests on a key principle of social psychology: people come to know the self by observing what they do, and observing others’ reactions to them. When a person prosumes content, this content becomes a mirror that reflects back identity meanings. This is particularly useful when making sense of content creation, consumption, and sharing on social media. Users create and share content in a social arena, receive feedback on it (even if that feedback is silence), and utilize the content, now tied to its’ elicited response, to both perform and learn about, the self.

For example, posting a Facebook image of my dogs is not only an outward performance of my affinity for these (incredibly adorable and wuvable) animals, but also a performance for myself. The image becomes a data point with which I come to know myself as a dog lover. This is further reinforced by comments and Likes, through which my network interacts with me as the kind of person who loves (her) dogs.

Certainly, identity prosumption predates social media. Foucault, for example, has written extensively on self-writing as a form of self-formation, relying on the examples of Greco-Roman Hupomnema and Christian confessions. Other examples include personal correspondence, diaries, and autobiographies. Extending beyond the written form, identity prosumption is well suited to theorize the identity meanings in scrapbooking, photo albums, quilting, and various forms of art.

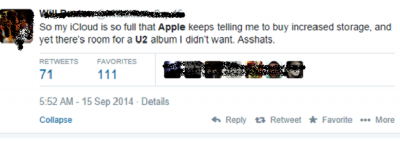

A digitally connected landscape, however, makes sharing in general, and prosumption in particular, a compulsory and public activity. Identity prosumption is not just a component of the social media experience, it is a central component. And with an increasing prevalence of social media as part of everyday sociality, identity prosumption becomes an integral component in processes of the self. To better understand identity prosumption, I want to try to break it down into integrated but distinct parts.

Prosuming Identity through Process and Artifact

To prosume is an act. That is, the prosumer is doing something. The result of this doing is an object. That is, the prosumer is making something. Both the act itself, and the consequent object, work back toward the prosumer in identity-constructive ways. I refer to these parts of identity prosumption as process and artifact.

Process is the doing. The bodily act of punching out a Tweet, or Tumblr post, or Snap, or Status Update, or Ello comment. It is the focus, anxiety, excitement, banality, or fear of creating the content and going live. The actor sees hirself engage these media, sees hirself articulate a message, sees hirself share—perhaps selectively— with hir network. What s/he sees hirself do informs who s/he defines hirself as.

The artifact is the result of this doing. It is the image, the story, the joke, the meme. It stares back at the actor from the glowing screen, evidence of who s/he is and what that means. Though individually relevant, artifacts prosumed through social media take on an aggregate character. In the case of social network sites, artifacts combine into what Hogan refers to as an Exhibition Space, or a curated collection of objects of the self. Even with ephemeral media (e.g., Snapchat), past prosumed artifacts linger in the networked memory, given nuance by their fleeting stay.

Though distinct, process and artifact are entwined. The process anticipates the artifact. The artifact refers back to the process. Both point to the identity meanings of the prosumer.For instance, if I share a funny story about my students, the content of that story (i.e., the artifact) is a means by which I perform—for myself and others—the role identity of academic, and the person identity of witty, or perhaps, cynical. This artifact points to the moments in which I constructed the narrative, decided to share, and agentically crafted this piece of performative content (i.e., the process).

We become subjects through the objects we prosume. These objects hold identity meanings in their very act of creation, and in the fruit that these acts of creation bear. In an age of digital connectivity, prosumptive activities become a key mechanism of identity performance and identity creation. I’m looking forward to continued exploration into the nooks and crannies of this line of theory.

Follow Jenny on Twitter: @Jenny_L_Davis

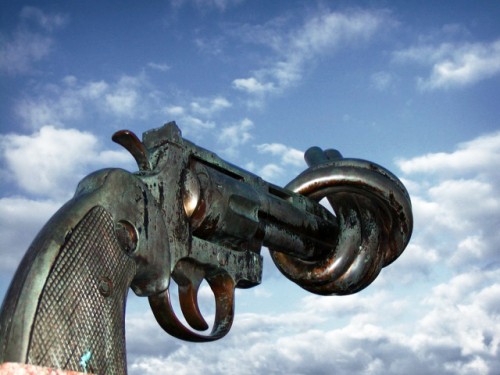

Headline Picture: Source