There’s a tricky balancing act to play when thinking about the relative influence of technological artifacts and the humans who create and use these artifacts. It’s all too easy to blame technologies or alternatively, discount their shaping effects.

Both Marshall McLuhan and Actor Network Theorists (ANT) insist on the efficaciousness of technological objects. These objects do things, and as researchers, we should take those things seriously. In response to the popular adage that “guns don’t kill people, people kill people,” ANT scholar Bruno Latour famously retorts:

It is neither people nor guns that kill. Responsibility for action must be shared among the various actants

From this perspective, failing to take seriously the active role of technological artifacts, assuming instead that everything hinges on human practice, is to risk entrapment by those artifacts that push us in ways we cannot understand or recognize. Speaking of media technologies, McLuhan warns:

Subliminal and docile acceptance of media impact has made them prisons without walls for their human users.

This, they get right. Technology is not merely a tool of human agency, but pushes, guides, and sometimes traps users in significant ways. And yet both McLuhan and ANT have been justly criticized as deterministic. Technologies may shape those who use them, but humans created these artifacts, and humans can—and do— work around them.

In working through the balance of technological influence and human agency, the concept of “affordances” has come to the fore. Affordances are the specifications of a technology which guide—but do not determine—human users. It is rare to read a social study of technology without reference to the affordances of the artifact(s) of interest. Although some argue the term is so widely used it no longer contains analytic value, I strongly believe its place remains essential. The power of “affordance” as an analytic tool is its recognition of technology as efficacious, without falling prey to the determinism of McLuhan and ANT.

We can, however, improve the nuance with which we employ the concept. Primarily, a delineation of affordances currently answers the question of “what?” That is, it tells us what component parts the artifact contains and what this implies for the user. For instance, the required gender designation of Facebook pushes users to identify their bodies into a single social category. The dropdown menu limits those options vis-à-vis a write in, but expands the options through multiple gender designations beyond male and female. These are some of the affordances of the Facebook platform, and they influence how users engage the platform in gendered ways. This is an important point, but I argue that we can better employ affordances through theorizing the “how?” in addition to the what. How for example, does Facebook push users to identify with a gender category? Do they make the user do so, or simply make it difficult for the user not to? In other words, the how tells us the degree of force with which the whats are implemented.

This issue of how came to me while talking with my students about technological affordances. An astute student asked about the difference between a wood privacy fence and a perimeter rope. They both afford the same thing, he correctly noticed, but in different ways. We collectively decided that while the fence tells you to stay off the property, the rope politely (though often effectively) asks.

I propose a rudimentary typology for the question of how, in which a technological affordance can request, demand, allow, or encourage. The first two refer to bids placed upon the user by the artifact. The latter two are the artifact’s response to (desired) user action. I welcome tweaks, suggestions, and of course applications.

Requests and demands move human users upon specific paths, with differing levels of insistence.

A technological artifact requests when it pushes a user in some direction, but without much force. This is an affordance a user can easily navigate around. For instance, Facebook requests that users include a profile image, but one can sign up and engage the service without doing so. Similarly, David Banks’ coffee maker requests that he live in a spacious home, but still agrees to make coffee in his modest residence.

A technological artifact demands when its use is conditioned on a particular set of circumstances. Facebook demands, for instance, that users select a gender category before signing up, and Keurig demands its users make coffee with Keurig brand K-cups. Although demand runs the risk of technological determinism, it is important to note that even demands can be rebuffed, though the obstacle may be significant. For instance, one might jailbreak an iPhone, subverting its demand that distribution rests solely with Apple. Or, with likely much greater difficulty, one might craft their own K-cup, subverting Keurig’s demand on brand loyalty. I think we could say/fight more about demands, but I’m kind of looking forward to hashing it out on Twitter and in the comments.

Thinking about the difference between request and demand, we can imagine signing up for some service through an online form. The form has several blank categories for the applicant to fill in. Those spots with red stars are required. Those without red stars are not required. The form therefore asks the applicant to fill in all of the information, but demands that they fill in particular parts.

The second two categories refer to an artifact’s response to those things a user may wish to do.

A technological artifact allows when its architecture permits some act, but does so with relative indifference or even disapproval. The Facebook status update allows users to post links, text, and images. One can post short quips or longer narratives. These narratives can potentially follow a variety of affective lines, such as joy, excitement, depression, or disappointment. Keurig allows users to make a variety of coffee flavors and strengths, offering a host of these through the machine-compatible brand. The user can also potentially run water through the same K-cup twice, reducing the value of each individual pod, though the technological artifact does not invite the user to do so.

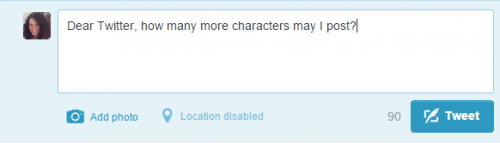

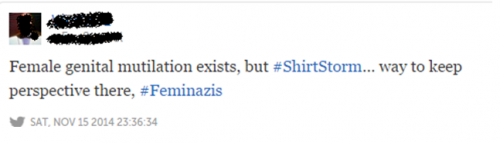

A technological artifact encourages when its architecture makes a particular line of action easy and appealing, especially vis-à-vis alternative lines of action. It fosters, breeds, nourishes something, while stifling, suppressing, discouraging something else. Facebook, for example, encourages users to produce content, providing a host of templates and a centrally located status update box complete with a prompt: “What’s on your mind?” It further encourages interaction by providing “notifications” of relevant activity at the top of the page in an eye-catching red font and sending these notifications to user’s mobile devices. Twitter, in turn, encourages short blips and link sharing, while Tumblr encourages longer form engagement. Both, like Facebook, encourage engaged interaction.

In examining the how, the what remains critically important. It is the what that the artifact requests, demands, allows, or encourages. Affordances enable and constrain. That is, they are always a product of, and subject to, human agency. However, facilitations and constraints operate at different levels. This typology is useful in understanding the degree to which each affordance is open to negotiation. It recognizes not only the mutual influence of human and machine, but the variable nature of this relationship.

Follow Jenny Davis on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis