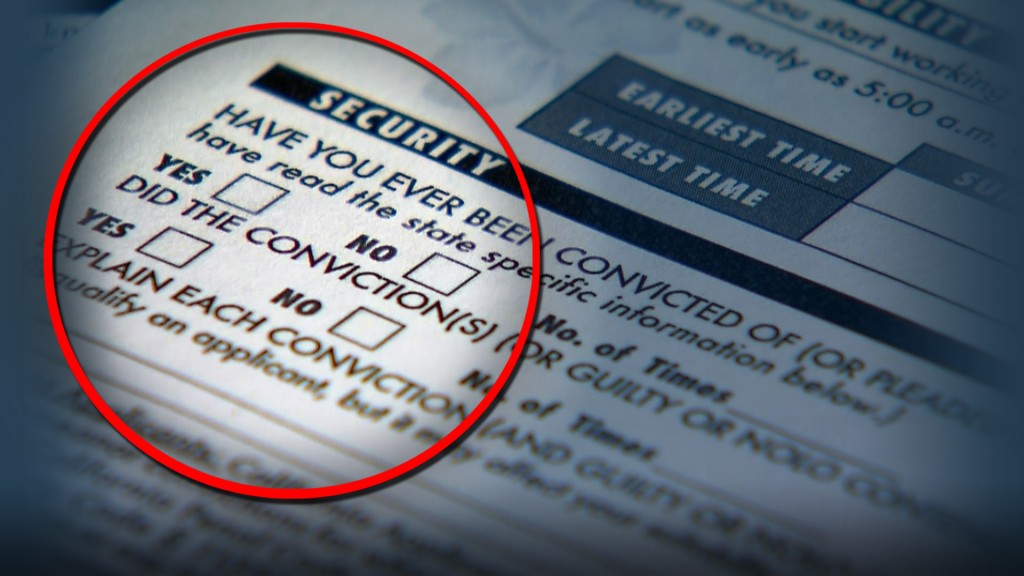

America has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world, and it is important to consider the long-lasting impacts that the criminal justice system can have on a person. This goes beyond the struggles of life inside or finding a job once they’re free — they can also lose their right to vote. In fact, due to laws which strip voting rights from people with convictions, over six million Americans will not be able to vote this November. This aggregate estimate comes from a new report by our very own Chris Uggen, TSP Editor and University of Minnesota Regents Professor, and his research team (which you can read about at Quartz, New York Times, Yahoo News, Democracy Now!, The Denver Post, Vogue, and others). Uggen explains,

“The message that comes across to them is: Yes, you have all the responsibilities of a citizen now, but you’re basically still a second-class citizen because we are not permitting you to be engaged in the political process.”

Public opinion is mixed on this issue, but people are generally okay if released prisoners within general society are allowed to vote, meaning legislation may be behind the times. In fact, consider that the 2000 election between Bush and Gore ended with a neck-and-neck finish in Florida decided by less than six-hundred votes. Today, Florida has one of the highest rates of felon disenfranchisement, and in 2000, such voters could have decided the race.

And speaking of “race,” laws which restrict felons from voting are in many ways a black-and-white issue. Because of such legislation, one in thirteen American black adults are not able to vote. As Uggen explains, felon disenfranchisement particularly hurts the African-American vote, a logical conclusion since the criminal justice system is already known to be racially disproportionate. These laws are often defended staunchly, but things may change in the future, and in large part thanks to work like this.