Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series:

- Has Borrowing Replaced Earning?

- Economic Decline and the American Dream

- Old Narratives and New Realities

Click on any image to expand. Since the 1980s, corporate profits have reached record levels, while the earnings and incomes of the middle class have stagnated or dropped. Yet, as former U.S. labor secretary Robert Reich and others point out, 80% of the American economy is driven by consumption spending. This means corporate profits are tied to consumption. But if wages and incomes have stagnated, what’s been driving the economy? Easily available consumer credit! The recent relationship between consumption, credit, and profits has severed the “virtuous cycle” between rising earnings, consumption, and profits that drove the U.S.’s economy from the end of World War II to the mid-1970s. In this cycle, consumption was driven by workers’ earnings, which rose steadily as the economy grew. Increases in wages fueled more consumption, which fueled more profits, more investment, higher wages, and still more consumption. In this environment, it wasn’t possible for profits to rise in the suites without earnings rising on the streets But then something changed. As Scott Fitzgerald and I argue in Post-Industrial Peasants: The Illusion of Middle Class Prosperity and Middle Class Meltdown, borrowing replaced earning as the major driver of consumer spending. This was made possible by the deregulation of financial markets and the lowering of credit and lending standards. The result was the 2008 financial markets crash, when investors and speculators lost confidence in that ability of people and corporations to make good on their debts.

The pre-2008 recession tie between consumption, credit, and profits has led us to question claims that things were peachy before and whether economic prosperity is just around the corner again. In the U.S., we have spent a great deal of time making life better for those who are already relatively wealthy. We’ve also harmed the economic prospects of everyone else. Middle-class families, whose main source of income is employment and main source of wealth is an owner-occupied home, have been losing big time. And their losses have been mounting for years. Easily available credit has essentially covered up these losses by boosting the spending power of those whose earning power was on the decline. Looking at the statistics, the path we’ve trod is pretty clear:- Since the late 1970s, the U.S. middle class has experienced an unprecedented decline in real purchasing power. The productivity gains of the 1980s and 1990s were not reflected in the average worker’s paycheck. Wages slid against inflation.

- Gaps between stagnant incomes and consumption aspirations were filled by easily available credit.

- Simultaneously, the deregulation of credit and financial markets that created many ways to lend money externalized the risk of bad loans through such unwieldy tools as “asset-backed securities” and “collateralized debt obligations.” Market risk was shifted from banks to the rest of us.

- The 2008 recession ended the era of easy credit.

- The middle class became, as Fitzgerald and I put it, a class of “post-industrial peasants.” Debt made the labor of middle-class workers look more like the serfdom of agrarian economies than the skilled work of modern citizens.

Profits Up, Wages…

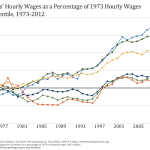

The evidence that profits have risen and wages and earnings have not is clear. While corporate profits and incomes for wealthiest tenth of tax-payers have risen steadily, median pre-tax family income has barely moved, rising less than 20% in real dollars since 1971.

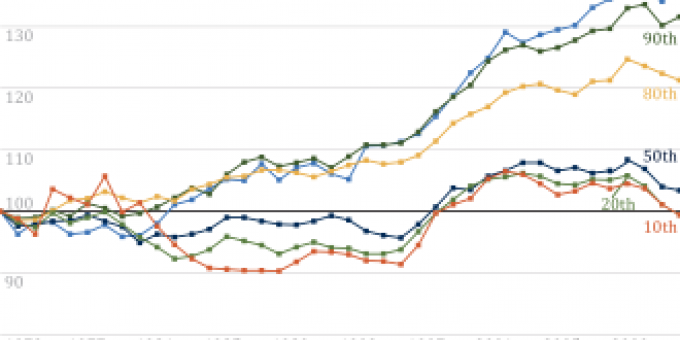

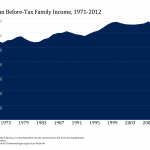

Wages among those already well off (that top 10% of the earnings distribution mentioned above) have ballooned since the 1970s while wages of the bottom 50% have barely moved at all. Further, according to the Economic Policy Institute, CEO compensation has increased 875% since 1978. Back then, the CEO-to-worker pay ratio was 29 to 1; by 2012, it was 273 to 1. In these years where wages were going nowhere, U.S. citizens were borrowing money (lots of it) and the savings rate effectively hit nothing by 2006 (the shaded areas on the chart below show the years in which the economy was in recession).

If the average American’s wages had risen along with productivity gains, the real median 1992 wage of $11.37 an hour would have risen to $19.15 today, rather than the real amount: $16.87 cents an hour. And $23,600 in 1992 would have translated into $34,300 in 2006. Since this change would have been in real dollars, the median wage earner would have seen her purchasing power increase by over a third, instead of just $800. That’s a lot of potential income going somewhere else for some other reason. Over the long term, it really does appear that the middle class replaced the purchasing power of nonexistent raises with easily available credit. The type of indentured servitude social scientists such as Juliet Schorr, Jacob Hacker, Dalton Conley, and others have discussed means many end up slaves to their debts, working more hours for less money (working hours have risen by 40% in the last 30 years), sending two adults into the labor market, and remaining stuck in a cycle of “spend, work, and pay debt.” With big debts, no savings, and no more laborers to add to the workforce, the great majority of families are only one missed paycheck away from defaulting on their bills. Perhaps worse, the 2008 recession brought the era of easy credit to a swift end. With credit now hard to obtain, the same families face large debts, small or missing paychecks, and creditors knocking on their doors.

Credit Then and Now

Many readers under 30 probably don’t remember the credit markets in place as recently as the mid-1980s. One had to apply for a credit card (usually from a bank). You had to prove that you had a job and report your income and any outstanding debts. If you were under 21, your parents had to co-sign the credit card application—essentially assuring that, if you did not pay back the debt, they would (and the card would have a low spending limit). The bank would look at your application, decide whether you were a good credit risk, and then set a limit on your credit card spending. If you came anywhere near the spending limit, the card was usually cancelled. You could no longer borrow until your debt was paid down. The same was true with auto and home loans. Applications were long and tedious, and there was little or no “instant credit.” Minimum down payments ranged between 10 and 20% of the full price of the car or house, and the bank or credit union spent a great deal of time evaluating your credit worthiness and whether you could afford the loan payments. Most interest rates were fixed (rather than variable) and they usually weren’t low (my first car loan came with a 17.5% interest rate in 1981; my first mortgage was 11.5% in 1990—two to three times today’s interest rates).

The deregulation of financial markets changed all of that. Big banks consolidated, and new lenders of all kinds started to sprout up to finance mortgages and auto loans. These new lenders were not subject to the same regulations as banks. Many bank regulations (limits on interest that could be charged, fees added, and limits on interstate banking and the consolidation of bank assets) were loosened. Loan terms eased considerably, and the creation of the asset-backed securities market meant that many loan originators didn’t even hold on to their outstanding loans – they sold the loans and their risk to securities firms that, in turn, sold the outstanding debt to investors willing to bet on riskier loans. That is, investors now took the risk that you might not be able to pay back your loan.Lured into a Cycle of Debt

Ironically, financial deregulation hit right as the squeeze of wage stagnation and job instability was most acute—the late 1980s to mid-1990s. Middle-class purchasing power was headed nowhere, when people started to get tempting credit card offers in the mail. “No proof of income necessary!” “Instant credit!” Suddenly you could drive a new car off the lot with no down payment or you could lease, rather than buy, it (returning the asset once the lease was up—essentially a long-term car rental). And for mortgages, many of the traditional loan eligibility restrictions were lifted, setting off an artificially inflated “housing boom” driven by easy credit and borrowed money. In extreme cases, home loans came with several introductory, “teaser” interest rates. In the early portions of the loan term, individuals might only pay the interest accrued in each period, ending up owing more each month if they only paid the minimum. In many cases, the teaser rates readjusted to higher, fixed interest rates after just a few years.

None of this has been helped by the serious and often hidden inflation affecting goods and services the middle class has come to rely on. As Elizabeth Warren and Amelia Tyagi pointed out in The Two-Income Trap, home prices in good neighborhoods have gone up 214% in the past 20 years. These good neighborhoods are “good” because they have good schools in them, and parents increasingly use two incomes as ammunition in the competition to buy a home in a good school district. But once they’ve secured this home, an interesting economic dance of deception is put in motion. Since jobs aren’t as steady as they once were and earnings don’t rise as they once did, that good home in that good neighborhood is a few missed paychecks away from foreclosure. But the deregulated credit market gives couples an array of options to try to “keep” the house while they try to secure more income: they can take out a second mortgage, raid retirement and college funds, and put mortgage payments on credit cards (in the rarer and rarer cases in which a couple has paid off their home, they can ease the pain of constricted retirement funds and Social Security payments by taking out a “reverse mortgage”: they will now be paid monthly for their home, slowly giving it away to an investor and hoping they won’t outlive the loan term). What else is getting more terrifyingly expensive? Well, we’ve allowed the cost of state-supported higher education to rise much faster than inflation. College is now a private good paid for through student loans, not a public good consistently supported by states. As any small business owner will tell you, employer provided health insurance is also becoming unaffordable, not only because employers are socked with big increases every year, but also because the payments expected by employees rise every year. While implementation of the Affordable Care Act will likely increase coverage, social scientists must begin asking more complicated questions about employer provided health insurance. Today, many employees don’t take the coverage their employer provides because they simply can’t afford it. And then there’s childcare: the average annual outlay for childcare in the U.S. is now almost $11,000 per child. If that average $972 per month per child is beyond the reach of all but the most secure members of the upper middle class, but high quality childcare is a key factor in strong school starts and the development of the cognitive and social skills to succeed as adults. That’s a tough choice. Meanwhile, the classic “defined-benefit” pension is almost gone. Stable retirement plans that guaranteed a minimum payout based on investments of company money and employee contributions have been replaced by 401K and other “defined-contribution” plans. These make the retirement of millions uncertain, based on their own savings and the performance of a deregulated financial market that few individuals understand. This is not a formula for success at any level.The New Virtuous Cycle

Record profits for corporations in the last decade have been produced almost entirely by lending money to middle-class consumers while letting their wages slide. The virtuous cycle connecting profits to the purchasing power created by jobs and earnings was severed—now all one needed to do was loan money to your customers (or get someone else to do it) and profits would follow (without the corresponding wages and job security once required of employers). The virtuous cycle that Robert Reich talks about has been recreated, but in a perverse form. Only the top one percent, whose incomes are derived from profits, dividends, and property ownership, can get in on the virtuous cycle and avoid the debt cycle.

The Obama Administration and its successors face a fairly unpalatable set of choices. The easiest is to simply turn the credit spigot back on, allow the securities aftermarket to spread the risks, and pray that there isn’t another crisis of confidence in the financial markets. That’s the easy road, but it will surely lead to more inequality and downward mobility. It would retain the trappings of middle-class status (houses, cars, vacations, and college educations) and the profits of companies. The harder choice means creating an alternate narrative that recognizes that family values cost money; that those who make a killing in financial markets should have to take other people with them; that the decision about whether to invest, save, and work shouldn’t be distorted by a tax system that favors unearned over earned income; and that lenders must be held accountable for the credit they advance to consumers. That alternative seems both idealistic and unattainable, but it’s neither. It is the type of realistic change that middle-class citizens should demand.Recommended Readings

Jacob Hacker and Paul Pearson. 2010. Winner Take All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer and Turned It’s Back on the Middle Class. New York: Simon & Schuster. Tells the story of how American politics created today’s enormous economic inequalities.

Kevin T. Leicht and Scott T. Fitzgerald. 2007. Post-Industrial Peasants: The Illusion of Middle Class Prosperity. New York: Worth Publishers.Documents the recent struggles of the American middle class, drawing connections with peasants in feudal societies and sharecroppers in agrarian societies.

Lawrence Mishel and Natalie Sabadish. 2013. CEO Pay in 2012 Was Extraordinarily High Relative to Typical Workers and Other High Earners. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. Comprehensive report on trends in the compensation of top executives.

Juliet Schor. 1998. The Overspent American: Why We Buy What We Don’t Need. New York: Basic Books. A critical analysis of American consumer culture.

Elizabeth Warren and Amerlia Warren Tyagi. 2004. The Two-Income Trap: Why Middle Class Parents are Going Broke. New York: Basic Books. Explains how two-income families are increasingly trapped by economic forces.

Comments 2

syed ali — July 2, 2014

frontline had this great doc on the secret history of the credit card. it's astounding and a definite must watch: http://video.pbs.org/video/1340904268/