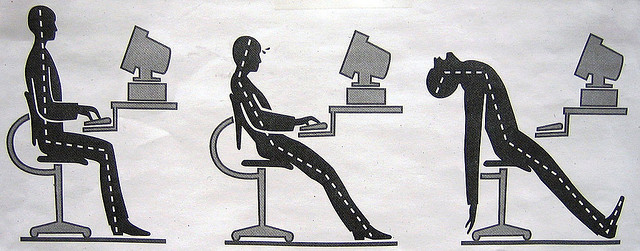

Black Friday is around the corner… as will be the long lines of people waiting for hot retail deals. This queuing up isn’t uncommon; we see people line up for grand openings, new gadgets, concert tickets, and even for free burritos and ice cream. Americans stand in line (often voluntarily) for approximately 37 billion hours a year. Why?

David Gibson, a sociologist at Notre Dame, draws our attention to the human desire to be part of a niche community,

these are people whose identities and stories about themselves are very much tied to being foodies, on being on the cutting edge of fashion and style, or being Apple device lovers. They get recognition, status, and buzz among their friends by showing up at these places and being the first person with a new iPhone.

Additionally, Gibson told CityLab that humans are more concerned with the length of the line than with how fast it is moving. To pass the time, he suggested that people should try to make friends with others; “If you’re actually queuing up for something which is coveted and exciting, then you’re kind of a member of a community to start with.” It would be easy to strike up a conversation because you already know what you have in common.

When it comes to cutting the line and saving spots, Gibson adds,

The important thing is that [others] see that you are tied to someone, and they’re willing to think that person was standing there on behalf of you. If there’s a limited number of devices or seats, and the people behind you think that an addition of a person is going to make a difference [in the wait time], that’s the only time that it will matter.