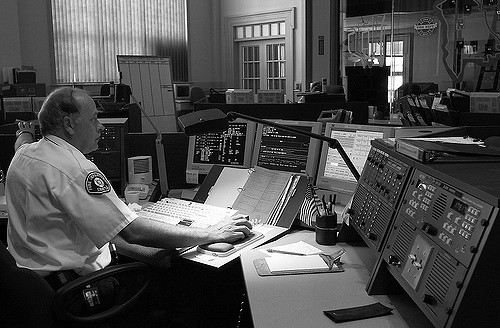

The relationship between communities and police officers is getting an increasing amount of attention, particularly the effect police violence has on communities. The Atlantic recently reported on a new study by sociologists Matthew Desmond, Andrew Papachristos, and David Kirk that explores how trust in the police often decreases after a community experiences police violence. After analyzing 911 calls made in Milwaukee from 2004 to 2010, the researchers found that instances of police violence had an impact on the number of 911 calls being placed.

The study began after the highly publicized beating of Frank Jude by police officers in Milwaukee in 2004, after which the authors found that 22,000 fewer calls were placed to 911. They discovered a similar pattern following the killing of Sean Bell in Queens, New York in 2006, and the assault of Danyall Simpson in Milwaukee in 2007. The researchers concluded that instances of police violence, both locally and nationally, have lasting effects on African American communities as whole. David Kirk says,

“Once the story of Frank Jude’s beating appeared in the press, Milwaukee residents, especially people in black neighborhoods, were less likely to call the police, including to report violent crime. This means that publicized cases of police violence can have a community-wide impact on crime reporting that transcends individual encounters.”

Papachristos added in a statement,

“Police departments and city politicians often frame a publicized case of police violence as an ‘isolated incident’ … No act of police violence is an isolated incident, in both cause and consequence. Seemingly isolated incidents of police violence are layered upon a history of unequal policing in cities.”