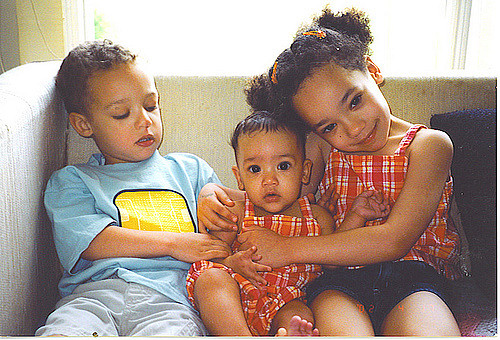

U.S. census estimates indicate that babies of color are now the majority and that by 2020, the majority of children under 18 will be non-white. Despite this growing diversity, many parts of the United States remain deeply segregated by race. A recent article in the Washington Post draws on U.S. census data and insights from sociologists Michael Bader, Kyle Crowder, and Maria Krysan to visually depict and explain the persistence of residential segregation in the United States.

Bader points out that the persistence of segregation is tied to the history of slavery, Jim Crow, and redlining practices against Black communities. Cities that have large African American populations, like Chicago and Detroit, have entrenched patterns of segregation. However, Krysan and Crowder argue in their book that housing policies and practices do not alone reproduce segregation. Daily routines and connections to others can also result in inequalities. As Krysan describes,

“We don’t have the integrated social networks. We don’t have integrated experiences through the city. It’s baked-in segregation, [Every time someone makes a move they’re] not making a move that breaks out of that cycle, [they’re] making a move that regenerates it.”

On the other hand, diversity in many suburbs has increased over the past decades. The D.C. metro saw a 300 percent increase in Hispanic American and a 200 percent increase in Asian American populations from 1990 to 2016. Bader connects this diversity in the suburbs to policy, arguing that both lower housing costs and the implementation of the Fair Housing Act helped to circumvent segregation,

“A lot of those areas were developed after the Fair Housing Act was implemented…If you’re building housing and you’re subject to the Fair Housing Act, you shouldn’t have, in those particular units, the legacy effects of segregation.”

While policy cannot address all residential segregation, it may lessen its reach.