In March, in an Instagram interview with Jameela Jamil, British pop star Sam Smith announced being non-binary in both gender and sexuality, stating “I’m not male or female. I think I float somewhere in between – it’s all on a spectrum” (timestamp 21:50 to 22.10). Smith had made a similar declaration to the Sunday Times in October, 2017, but did not suggest that the media use non-binary gender pronouns at the time. During the interview, Smith also revealed that “the basis of all my sadness” has been body shaming.

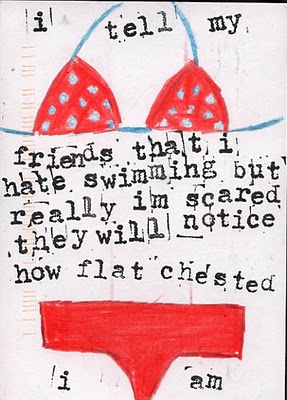

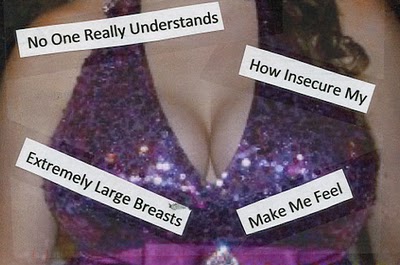

This instance of “biography and history” producing a non-binary person haunted by fat-shaming is important to the sociological understanding of gender. It reminds us that gender is lived in the body, not just as an idea but as a “looking-glass self” in which multiple kinds of stigma can simultaneously reduce a person to a “tainted, discounted one”. As culture shapes the way we see ourselves, it can produce an overpowering feeling of what Cooley called “mortification,” because “we always imagine, and in imagining share, the judgments of the other mind.” In Mead’s terms, culture produces this in the “generalized other”; how we imagine ourselves as an object in the eyes of the whole society.

The intersection of body-shaming and transphobia shows us how bullying turns the body into an object. Jamil recounted in the interview that a photographer had called her a “fat c-word.” This can be compared with C.J. Pascoe’s famous study of how the word “fag” is used in bullying to police the gender of boys. Smith concludes the interview with a vow to promote self-forgiveness and the love of the body. This struggle against the gender binary fits within the mission of Jamil’s “I Weigh” instagram series seeking to resist all forms of cultural bullying and policing of bodies, gender expression and sexuality.

Jonathan Harrison, PhD, is an adjunct Professor in Sociology at Florida Gulf Coast University, Florida SouthWestern State College and Hodges University whose PhD was in the field of racism and antisemitism.