This is the third part in a series about how girls and women can navigate a culture that treats them like sex objects. See also parts One and Two. Cross-posted at Ms. and Caroline Heldman’s Blog.

This post outlines four damaging daily rituals of objectification culture we can immediately stop engaging in to improve our health.

1) Stop seeking male attention.

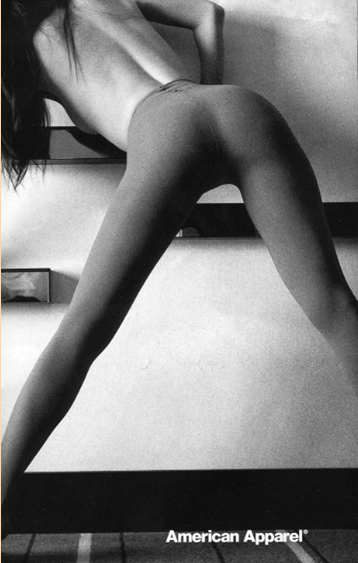

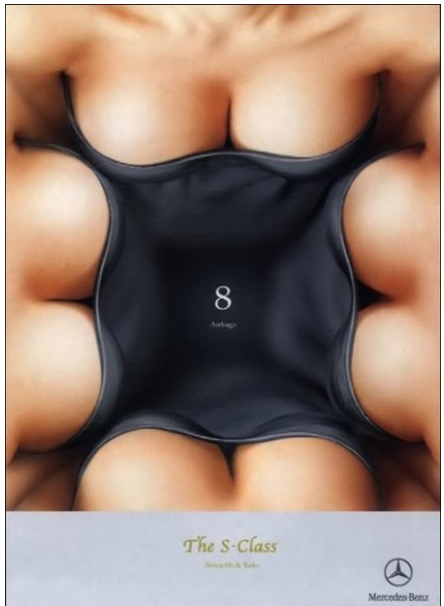

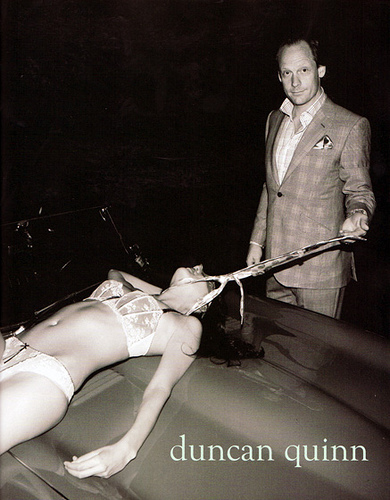

Most women have been taught that heterosexual male attention is the Holy Grail and its hard to reject this system of validation, but we must. We give our power away when we engage in habitual body monitoring so we can be visually pleasing to others. The ways in which we seek attention for our bodies varies by sexuality, race, ethnicity, and ability, but the template is the “male gaze.”

Heterosexual male attention is actually pretty easy to give up when you think about it.

- First, we seek it mostly from strangers we will never see again, so it doesn’t mean anything in the grand scheme of life. Who cares what the man in the car next to you thinks of your profile? You’ll probably never see him again.

- Secondly, men in U.S. culture are raised to objectify women as a matter of course, so an approving gaze doesn’t mean you’re unique or special, it’s something he’s supposed to do.

- Thirdly, male validation is fleeting and valueless; it certainly won’t pay your rent or get you a book deal. In fact, being seen as sexy hurts at least as much as it helps women.

- Lastly, men are terrible validators of physical appearance because so many are duped by make-up, hair coloring and styling, surgical alterations, girdles, etc. If I want an evaluation of how I look, a heterosexual male stranger is one of the least reliable sources on the subject.

Fun related activity: When a man cat calls you, respond with an extended laugh and declare, “I don’t exist for you!” Be prepared for a verbally violent reaction as you are challenging his power as the great validator. Your gazer likely won’t even know why he becomes angry since he’s just following the societal script that you’ve just interrupted.

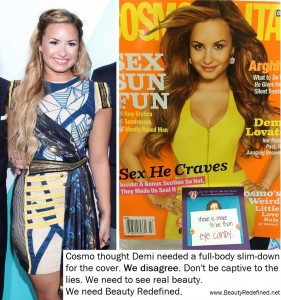

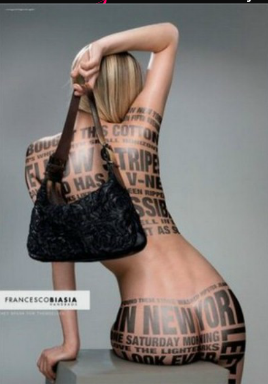

2) Stop consuming damaging media.

Damaging media includes fashion, “beauty,” and celebrity magazines, and sexist television programs, movies, and music. Beauty magazines in particular give us very detailed instructions for how to hate ourselves, and most of us feel bad about our bodies immediately after reading. Similar effects are found with television and music video viewing. If we avoid this media, we undercut the $80 billion a year Beauty-Industrial Complex that peddles dissatisfaction to sell products we really don’t need.

Related fun activity: Print out sheets that say something subversive about beauty culture — e.g., “This magazine will make you hate your body” — and stealthily put them in front of beauty magazines at your local supermarket or corner store.

3) Stop Playing the Tapes.

Many girls and women play internal tapes on loop for most of our waking hours, constantly criticizing the way we look and chiding ourselves for not being properly pleasing in what we say and what we do. Like a smoker taking a drag first thing in the morning, many of us are addicted to this self-hatred, inspecting our bodies first thing as we hop out of bed to see what sleep has done to our waistline, and habitually monitoring our bodies throughout the day. These tapes cause my female students to speak up less in class. They cause some women to act stupidly in order to appear submissive and therefore less threatening. These tapes are the primary way we sustain our body hatred.

Stopping the body-hatred tapes is no easy task, but keep in mind that we would be utterly offended if someone else said the insulting things we say to ourselves. Furthermore, we are only alive for a short period of time, so it makes no sense to fill our internal time with negativity that only we can hear. What’s the point? These tapes aren’t constructive, and they don’t change anything in the physical world. They are just a mental drain.

Related fun activity: Make a point of not worrying about what you look like. Sit with your legs sprawled and the fat popping out wherever. Walk with a wide stride and some swagger. Public eating in a decidedly non-ladylike fashion is also great fun. Burp and fart without apology. Adjust your breasts when necessary. Unapologetically take up space.

4) Stop Competing with Other Women.

The rules of the society we were born into require us to compete with other women for our own self-esteem. The game is simple. The “prize” is male attention, which we perceive of as finite, so when other girls/women get attention, we lose. This game causes many of us to reflexively see other women as “natural” competitors, and we feel bad when we encounter women who garner more male attention, as though it takes away from our worth. We walk into parties and see where we fit in the “pretty girl pecking order.” We secretly feel happy when our female friends gain weight. We criticize other women’s hair, clothing, and other appearance choices. We flirt with other women’s boyfriends to get attention, even if we’re not romantically interested in them.

Related fun activity: When you see a woman who triggers competitiveness, practice active love instead. Smile at her. Go out of your way to talk to her. Do whatever you can to dispel the notion that female competition is the natural order. If you see a woman who appears to embrace the male attention game, instead of judging her, recognize the pressure that produces this and go out of your way to accept and love her.

Stay tuned for Sexual Objectification, Part 4: Daily Rituals to Start.

Caroline Heldman is a professor of politics at Occidental College. You can follow her at her blog and on Twitter and Facebook.