Opponents of abortion have long targeted the “demand side” of abortion by passing legislation aimed at dissuading patients from going through with an abortion. Examples of this type of restriction include parental consent/notification laws, waiting periods, and mandatory counseling. Research shows that targeting patients has had little impact on national abortion rates; they’ve been declining, but several factors are likely contributing to the decrease, including increased accessibility to contraceptives.

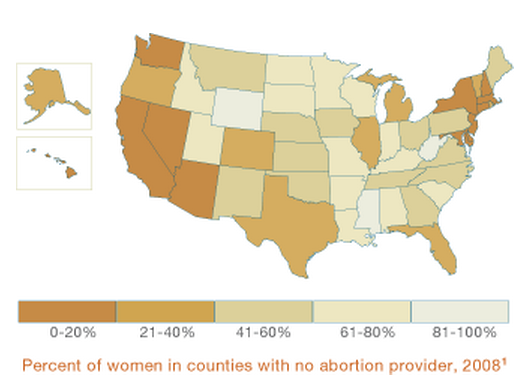

New approaches to restricting abortion have focused on the “supply side” of the abortion equation — that is, targeting the doctors and clinics that provide abortions. These regulations often require certain staffing and equipment requirements, resulting in clinics being shut down (often due to the expense of implementing the regulations). Reduced access to clinics often means that women have to travel further for an abortion — increasing costs (the procedure itself, travel, and accommodations), especially when a patient has to navigate waiting periods and counseling requirements.

Mississippi’s sole abortion clinic, for example, the focus of abortion opponents for many years, faced closure recently because of a law that changed licensing procedures. The law now requires all doctors performing abortions to have admitting privileges at local hospitals (difficult for the out-of-state doctors to acquire). The clinic was granted an extension to meet the requirements, though the law was allowed to stand.

So, does targeting the supply side of abortion work to reduce the procedure?

A recent article in the New England Journal of Medicine did a natural experiment to answer this question. In 2004, Texas passed two new restrictions on abortion, one on each side. The “demand side” legislation required that women receive information about risks at least 24 hours before an abortion can be performed. The “supply side” legislation required that abortions after 16 weeks of gestation be performed in a hospital or an ambulatory surgical center instead of a clinic. At the time the law was passed, none of Texas’ non-hospital based clinics met the legal requirements, and very few abortions were performed in hospitals.

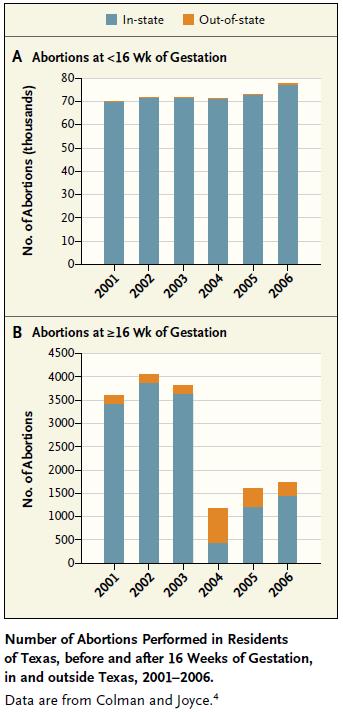

If the “demand side” legislation had an effect, the number of abortions would decrease at all levels of gestation. As Chart A illustrates, there was no change whatsoever in the number of abortions performed before 16 weeks — indicating that the demand side legislation had almost no impact.

If the supply-side legislation had an effect, the number of abortions provided after 16 weeks should have dropped. In fact, Chart B shows that the number of later abortions performed dropped 88% after the legislation was implemented.

So, targeting the supply side reduced the number of abortions performed in Texas, but did the women carry their baby to term?

No. Some of these women left the state to receive an abortion; in fact, the number of who received an out-of-state abortion more than quadrupled from 2003 to 2004. Accordingly, the average distance women had to travel to receive an abortion after 16 weeks increased from 33 miles in 2003 to 252 miles in 2004.

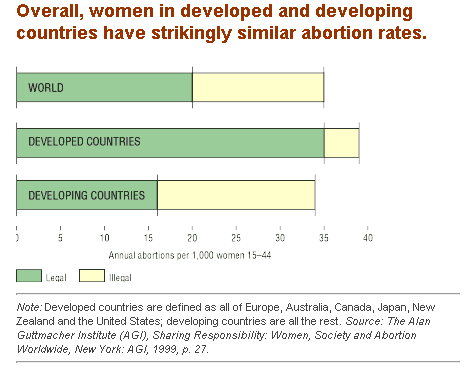

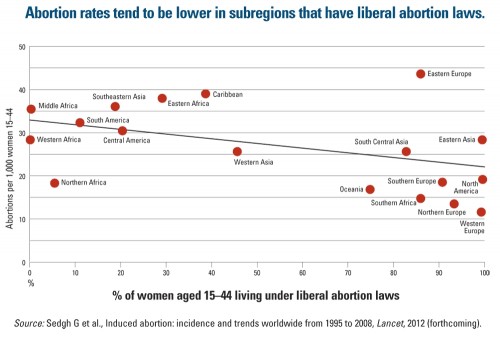

As has been noted on this site before, nations that have highly restrictive abortion laws do not have lower abortion rates; in fact, in those countries where abortion is illegal, many of those abortions are unsafe, resulting in high numbers of maternal deaths. Although targeting the supply-side of abortion might be appealing, it will probably not reduce the abortion rate nationwide. Instead, it likely places onerous restrictions on women with fewer resources, since they will be less able to meet the increased costs that result from having to travel for abortions.

Thanks to Jenna for the submission!

————————

Amanda M. Jungels is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Sociology at Georgia State University, focusing on sexuality, gender, and cognitive sociology. Her dissertation focuses on disclosures of private information at in-home sex toy parties. She is the current recipient of the Jacqueline Boles Teaching Fellowship, given to outstanding graduate student instructors.