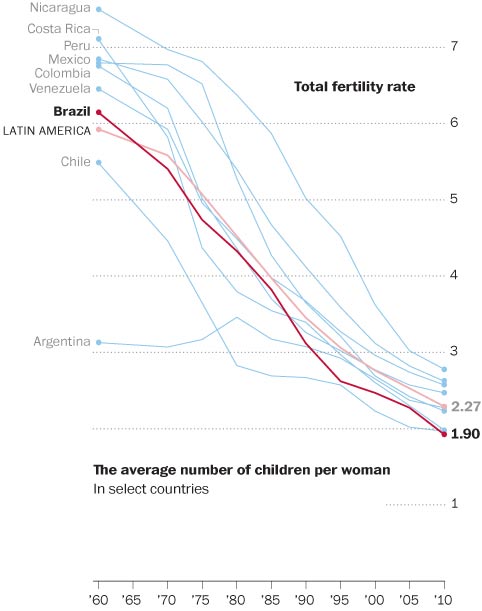

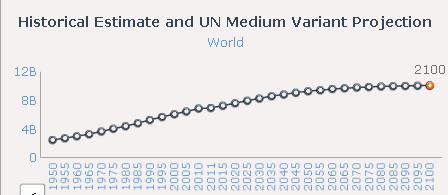

The declining birth rate in Latin America, depicted in this graph, is a nice example of the way that both cultural and social change affects individual choices. Brazil is highlighted as an extreme case. It’s birthrate has fallen from over six children/woman in 1960 to under 1.9 today.

The accompanying Washington Post article, sent in by Mae C., explains that the decrease in the birthrate since the 1960s is related to migration to cities. In rural areas children are useful. They can help with crops and animals. In crowded and expensive cities, however, they cost money and take up space. Economic change, then, changed the context of individual choices.

This transition — from a largely rural country with high birthrates to an industrialized one with lower birthrates — has been observed across countries again and again. It’s no surprise to demographers (social scientists who study changes in human population). But Brazil did surprise demographers in one way:

…Brazil’s fertility rate fell almost uniformly from cosmopolitan Sao Paulo, with its tiny apartments and go-go economy, to Amazonian villages and the vast central farming belt.

The decline in birthrate, in other words, has occurred across the urban/rural divide. Demographers attribute this to cultural factors. The idea of “an appealing, affluent, highflying world, whose distinguishing features include the small family” has been widely portrayed on popular soap operas, while Brazilian women in the real world have made strong strides into high-status, well-paid, but time-intensive occupations. They mention, in particular, Brazil’s widely-admired first female president, Dilma Rousseff, who has one child.

Ultimately, then, the dramatic drop in the birthrate is due to a combination of both economic and cultural change.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.