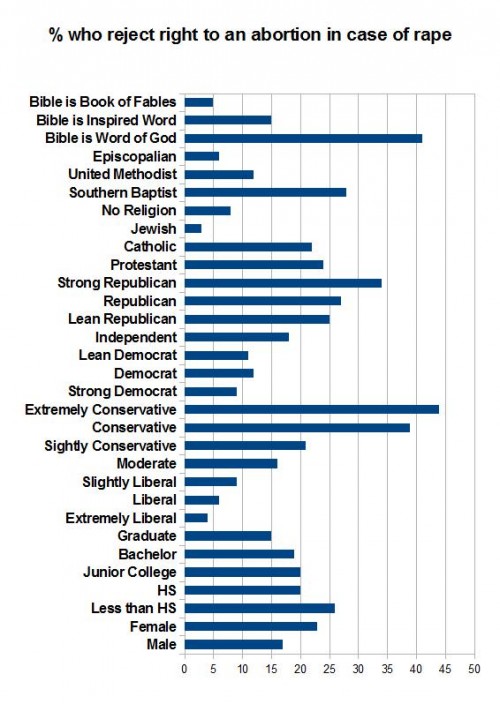

Yesterday was the anniversary of the landmark Roe v. Wade decision. On January 22, 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down the landmark case establishing women’s right to an abortion (though not an unrestricted right).

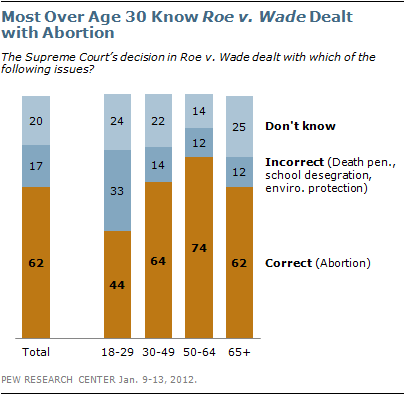

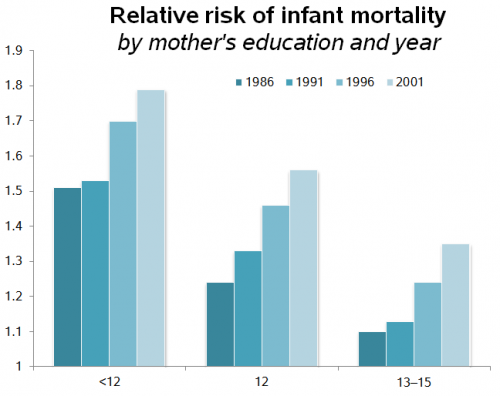

The Pew Research Center released some data on current public knowledge and opinion about abortion in the U.S. They found that well under half (44%) of younger people — those under 30 — knew what Roe v. Wade was about. A quarter said they didn’t know, and a third thought it was about another issue. This was a much lower level of familiarity than older age groups:

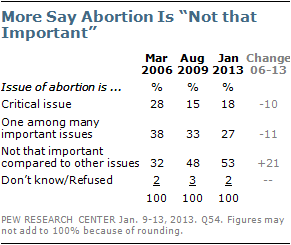

Abortion is still certainly a contentious issue, but it may not be quite the galvanizing cultural flashpoint it once was. Indeed, fewer people seem to see it as a critical issue. A growing percent of respondents say that abortion isn’t all that important — now over half say so:

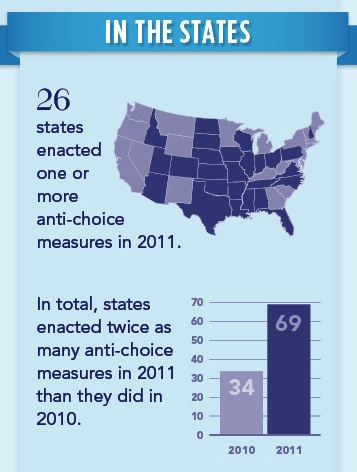

That seems to indicate a lessening of the intensity of the culture war surrounding abortion. That could mean less intensity in opposition to abortion (most respondents thought it should be legal, though many personally thought it was morally wrong), but it may also lead to less resistance to the types of restrictions on clinics that leave abortion technically legal, but so difficult to access that it’s a hollow legality.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.