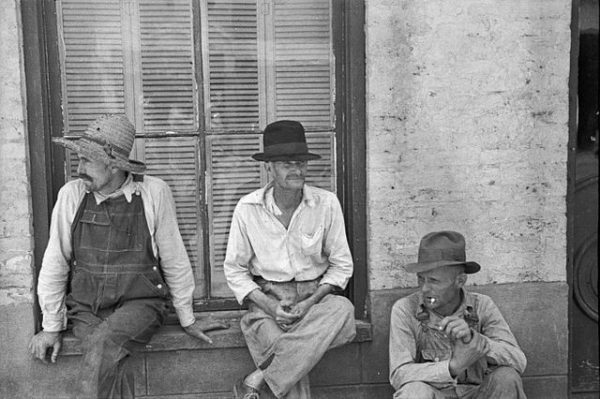

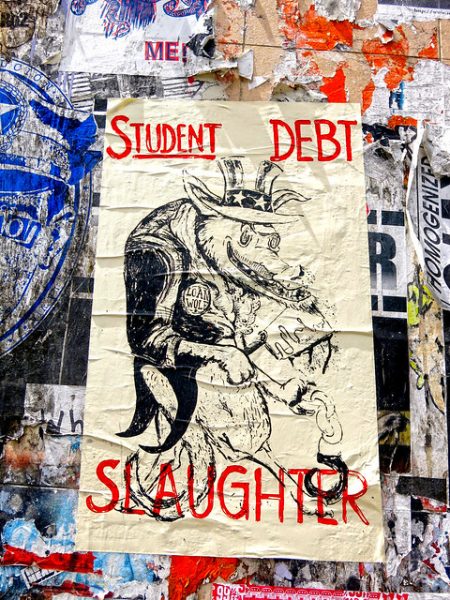

During times of crisis, existing prejudices often become heightened. Fears about the current coronavirus, or COVID-19, have revealed rampant racism and xenophobia against Asians. Anti-Asian discrimination ranges from avoiding Chinese businesses to direct bullying and assaults of people perceived to be Asian. This discriminatory behavior is nothing new. The United States has a long history of blaming marginalized groups when it comes to infectious disease, from Irish immigrants blamed for carrying typhus to “promiscuous women” for spreading sexually transmitted infections.

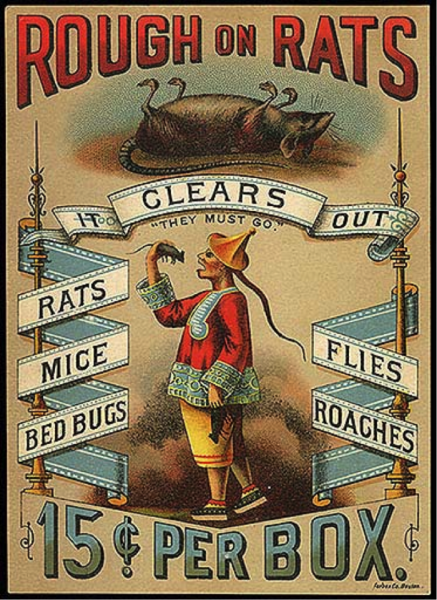

Historically, the Chinese faced blame time and again. In the 19th century, public health officials depicted Chinese immigrants as “filthy,” carriers of disease. These views influenced Anti-Chinese policies and practices, including humiliating medical examinations at Angel Island — the entry port for many Chinese immigrants coming to America — and the violent quarantine and disinfection of San Francisco’s Chinatown in the early 20th century when a case of the Bubonic plague was confirmed there.

- Nayan Shah. 2010. Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown. University of California Press.

- Erika Lee and Judy Yung. 2010. Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America. Oxford University Press.

- Alan Kraut. 1994. Silent Travelers: Germs, Disease, and the Immigrant Menace. Basic Books.

- Howard Markel and Alexandra Minna Stern. 2002. “The Foreignness of Germs: The Persistent Association of Immigrants and Disease in American Society.” The Milbank Quarterly 80(4): 757-788.

Discrimination against the Chinese is one example among many. Such discrimination had nothing to do with their actual hygiene and health, and everything to do with their social position relative to other racial groups. It’s easy to look back on the xenophobic U.S. policies and behavior in earlier times. Let’s not fall into the same patterns today.

For more on xenophobia and coronavirus, listen to Erika Lee on a recent episode of NPR’s podcast, Code Switch.