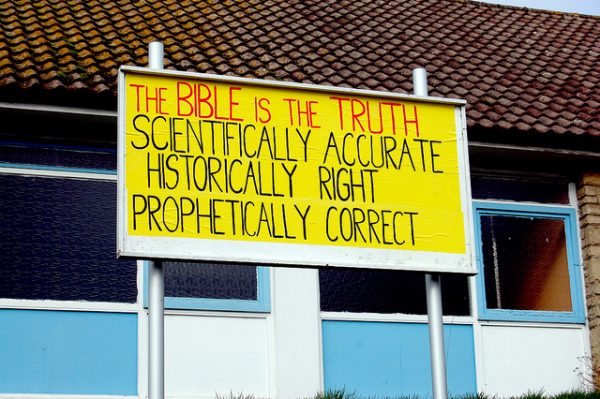

Teaching about race and racism in school systems and classrooms is a complex task, and crafting curricula and policies in these areas are even more so. As recent debates over history textbooks and lesson plans about slavery illustrate, race and racism are often emotional and controversial, and vary from community to community, state to state, or nation to nation. The notion of “antiracism” has been another recent touchstone — and research on the topic may lead to more informed policies and decisions on how to address racism in educational contexts.

In its definition, antiracism confronts racism and challenges White gains from the exclusion and oppression of people of color, even if those gains are unintentional. Antiracism in education follows these tenets, by focusing on racial inclusiveness and questioning how conceptions of race and racism have shaped what counts as knowledge.

David Gillborn. 2008. “Developing Antiracist School Policy.” Pp. 246-251 in Everyday Antiracism: Getting Real About Race in School. New York: The New York Press.

Audrey Thompson. 1997. “For: Anti-racist Education.” Curriculum Inquiry 27(1): 7-44.

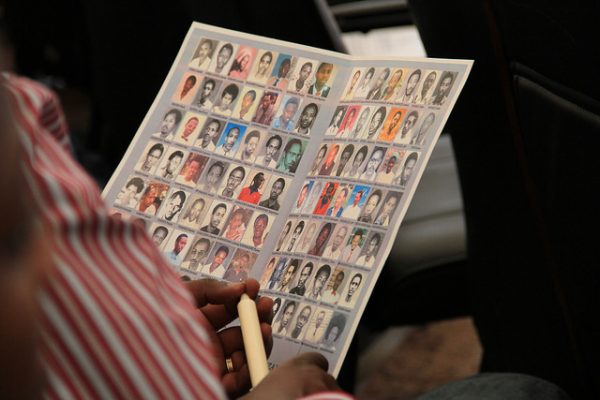

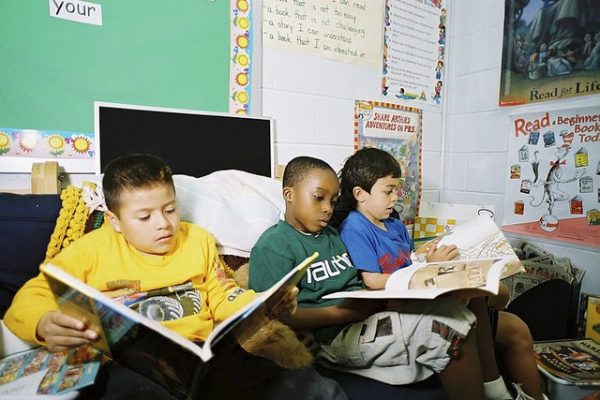

Many antiracist education programs focus on White individuals, assuming that Whites are the main actors that can produce change, but also major obstacles to progress. But research suggests that students of color are also an important part of the teaching and learning process. These students can bring their own personal experiences — which can’t be learned from books — into the classroom and thus, these students can be instrumental in promoting antiracist change. Involving communities of color in educational processes, by informing students on African languages, cultures, and heritage, for example, can promote collective learning and knowledge production to benefit both students of color and White students.

David Gillborn. 1996. “Student Roles and Perspectives in Antiracist Education: A Crisis of White Ethnicity?” British Educational Research Journal 22(2): 165-179.

George J. Sefa Dei. 2008. “Schooling as Community: Race, Schooling, and the Education of African Youth.” Journal of Black Studies 38(3): 346-366.