The newest Apple Watch can now warn users when it detects an abnormal heartbeat. While Apple may be on the cutting edge, many people have been using apps to track their food intake and exercise for some time. Social science research demonstrates that health-tracking technology reflects larger social forces and institutions.

These health-tracking apps are part of a larger trend in American medicine that researchers call “biomedicalization,” which includes a greater focus on health (as opposed to illness), risk management, surveillance, and includes a variety of technological advances.

- Adele E. Clarke, Janet K. Shim, Laura Mamo, Jennifer Ruth Fosket, and Jennfier R. Fishman. 2003. “Biomedicalization: Technoscientific Transformations of Health, Illness, and U.S. Biomedicine.” American Sociological Review 68: 161–94.

- David Armstrong. 1995. “The Rise of Surveillance Medicine.” Sociology of Health and Illness 17: 393–404.

Benefits of using these apps include empowering patients and not having to rely on doctors for knowledge about one’s body, which — as many of the apps advertise — may save time and money by potentially allowing them to avoid doctor visits. However, self-tracking may put more onus on the individual to maintain their health on their own, leading to blame for those who do not take advantage of this technology. Further, using this technology could lead to strain in doctor-patient relationships if doctors believe patients are undermining their authority.

- Deborah Lupton. 2016. The Quantified Self: A Sociology of Self-Tracking. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Deborah Lupton and Annemarie Jutel. 2015. “‘It’s Like Having a Physician in Your Pocket!’ A Critical Analysis of Self-Diagnosis Smartphone Apps.” Social Science & Medicine 133: 128–35.

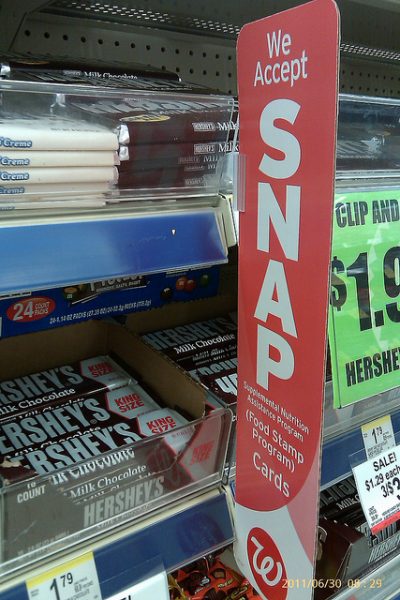

As more and more Americans use smartphones, the promise of digital technology, including health-tracking apps, for reducing existing health disparities grows. However, the Pew Research Center shows large income and educational gaps still exist in smartphone use, meaning the health benefits of using such technology — as well as potential downfalls — for the greater population, may be a long way off.