For many across the globe, the Olympics is a chance to celebrate a shared human connection, athletic achievement, and national pride. The Olympic Charter claims the Games encourage friendship, cross-cultural understanding, and world peace, but to do so the games must be free of politics. The Olympics present an opportunity to cross divisive diplomatic lines, like the temporary calming of tensions between North and South Korea. But these ideals may be overly optimistic as these global events have real political effects.

- John J. MacAloon. 1982. “Double Visions: Olympic games and American Culture.” The Kenyon Review 4(1): 98-112.

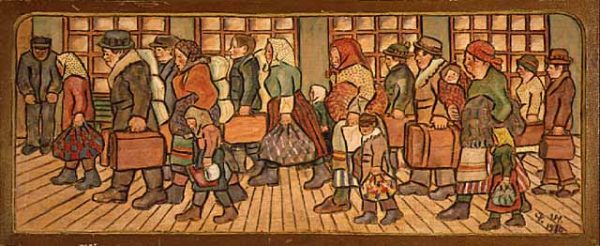

Historically, only the economic and social elite participated in the Olympics, so other versions like the Worker’s Games countered the Olympic Games in the early 1900s. In addition, the Olympics themselves have become a space to challenge the status quo. Protests, or lack thereof, can challenge or reinforce global norms.

- Douglas Hartmann. 2003. Race, Culture, and the Revolt of the Black Athlete. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Arnd Krüger and William Murray (eds.). 2003. The Nazi Olympics: Sport, Politics, and Appeasement in the 1930s. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Rob Millington and Simon C Darnell. “Constructing and Contesting the Olympics Online: The Internet, Rio 2016 and the Politics of Brazilian Development.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 49(2): 190-210.

Sporting events like the Olympics may allow nations to compete with each other without the consequences of war. Non-violent competition is even more important in the modern world, where technology allows for increasingly lethal methods of warfare. This may be one reason nations financially invest in producing elite athletes and could be behind recent controversies, like the Russian doping scandal.

- J.A. Mangan (ed.). 2004. Militarism, Sport, Europe: War Without Weapons. London: Frank Cass Publishers.

- Lincoln Allison and Terry Monnington. 2002. “Sport, Prestige and International Relations.” Government and Opposition 37(1): 106-134.

Though intended to be apolitical, nations may attempt to use the Olympics to sway global public opinion. Foreign policy officials report that political rebranding was a key reason to host the games. Modern media channels make this motivation even more powerful than in decades past, as nations know that the Olympics will have extensive global coverage.

- Jarol B. Manheim. 1990. “Rites of Passage: The 1988 Seoul Olympics as Public Diplomacy.” Political Research Quarterly 43(2): 279-295.

- Kevin Young and Kevin B. Wamsley. 2005. Global Olympics: Historical and Sociological Studies of the Modern Games. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Alan Tomlinson and Christopher Young. 2006. National Identity and Global Sports Events: Culture, Politics, and Spectacle in the Olympics and the Football World Cup. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Lee Humphreys and Christopher J. Finlay. 2008. “New Technologies, New Narratives” Pp. 284-306 in Owning the Olympics: Narratives of the New China. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.