About Us

AJUS is dedicated to the proposition that every idea deserves a platform. We welcome dissertation chapters, voice memos, vague thoughts, lecture notes, and data analysis that speaks for itself. Use your sociological imagination.

Manuscript Types

- Theoretical Speculations – Wildly ambitious frameworks with no empirical evidence.

- Data? – Raw numbers in an Excel file, preferably unformatted.

- Ethnographic Musings – 1-2 notes jotted down on a used napkin.

- Methodological Hot Takes – No actual study, just vibes.

- Unfinished Dissertations – Someone, someday might just read it.

Submission Guidelines

- Proposing sociological questions?

- Fully conceptualized, partially completed work is acceptable.

- Include 1+ cite(s) you “meant to look up later.”Placeholders and “TBD” acceptable.

- Feature tables and figures that may or may not be related to the topic.

- Write the conclusion at 2 AM, ideally over- or under-caffeinated.

- ORCHID ID required.

Formatting Requirements

- Length: We encourage all manuscripts to be between 500 words and wherever your heart tells you to stop.

- Proofreeding optional.

- Font: Something not so basic, expand your horizons.

- Citations: Surprise us. APA, MLA, CFG, SSD, GHD, DGD, NFL, NHL, KCF…

- Abstract: Don’t be too, somewhat vague.

- References: Don’t forget anyone, because we will send it to whomever you forget to cite…

References: Don’t forget anyone, because we will look through and will send it to whomever you forgot to cite…

Peer Review Process

All submissions will undergo our patented Mega-Triple-Blind Peer Review System™, where:

- The authors forget what they wrote.

- The reviewers skim the abstract and pick 1 or 2 arbitrary things to call out.

- The editors decide based on their breakfast.

We guarantee comprehensive feedback (e.g., “Interesting…” and “?”).

If your paper is rejected, you may submit an appeal by:

- Resending the same manuscript in a different font.

- Signing an affidavit attesting that “Foucault would have accepted this.”

- Threatening to start your own journal.

How to Submit:

Send your completed-ish manuscript via:

- A blurry PDF screenshot in an email attachment labeled “Final_Draft_3_(Actually_Final).doc”

- A Google Doc with unresolved comments.

- Mail.

- AJUS Signal Editors Only Group Chat.

- Give us a call and read it aloud: (715) 600-2187 (after 10:33 PM only)

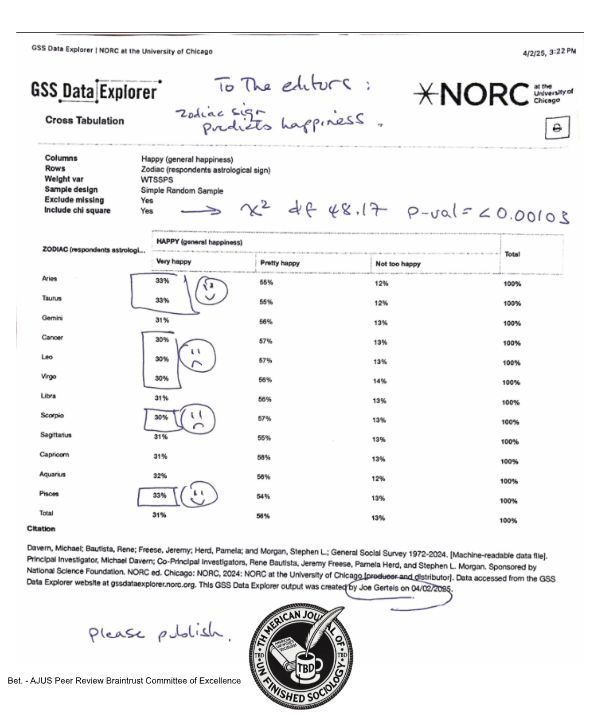

2025 Issue | Outside the Box Thinkers

Zodiac Sign Predicts Happiness