“Since the first Diversity and Inclusion Coaching Mobility Report in 2013, it has

NfL Releases diversity and inclusion report, February 28, 2022

been noted that the NFL has led the sports industry by intentionally hiring a diverse and inclusive workforce, as well as increasing opportunity for minority coaches,” said National Football League Executive Vice President Troy Vincent Sr.

Racism in SportsWorld is an important subject for scholars and for the public, in part because it directly challenges the myth of American meritocracy. The average college or professional football fan may seldom question why the coaching ranks are overwhelmingly dominated by white men, while the majority of the players are Black. Nevertheless, scholars have spent decades investigating why Black players have struggled to parlay their experiences and talents into professional positions that would permit them to work until a more normative retirement age. The recommended reading at the conclusion of this piece offers some exemplary work on these questions.

As the quote that opens this piece suggests, the National Football League (NFL) claims to intentionally hire a diverse and inclusive workforce. Yet the data do not support this claim. In the fall of 2022, on the eve of the 20th anniversary of the “Rooney Rule” that established standard NFL hiring practices for head coach searches, the Washington Post ran an in-depth series on the continuing dearth of Black NFL head coaches.

The Data

According to the Post, the NFL did not cooperate with their investigation and provide access to their own hiring data.

The Post asked the NFL multiple times to provide data to aid reporters’ efforts. A spokeswoman said in July that the league could not provide any of the data The Post requested, which included aggregate demographics on a season-by-season basis for head coaches, coordinators, position coaches and players. The Post also asked the NFL to verify coaches’ dates of birth and racial identification. In the days before this story published, the league provided The Post with four tables that showed the aggregate demographics of head coaches, offensive coordinators, defensive coordinators and special teams’ coordinators over a 21-year span — not separated by season…without data directly from the NFL…”

“How The Post gathered and analyzed data for its series on Black NFL coaches,” Giambalvo and Morse, September 21, 2022

We find this troubling and indicative of the league’s knowledge of their race problem. So we decided to reexamine the data reported in the Washington Post Series, and then compile and analyze additional open-source data from the pro-football reference website and each coach’s individual page within this site.

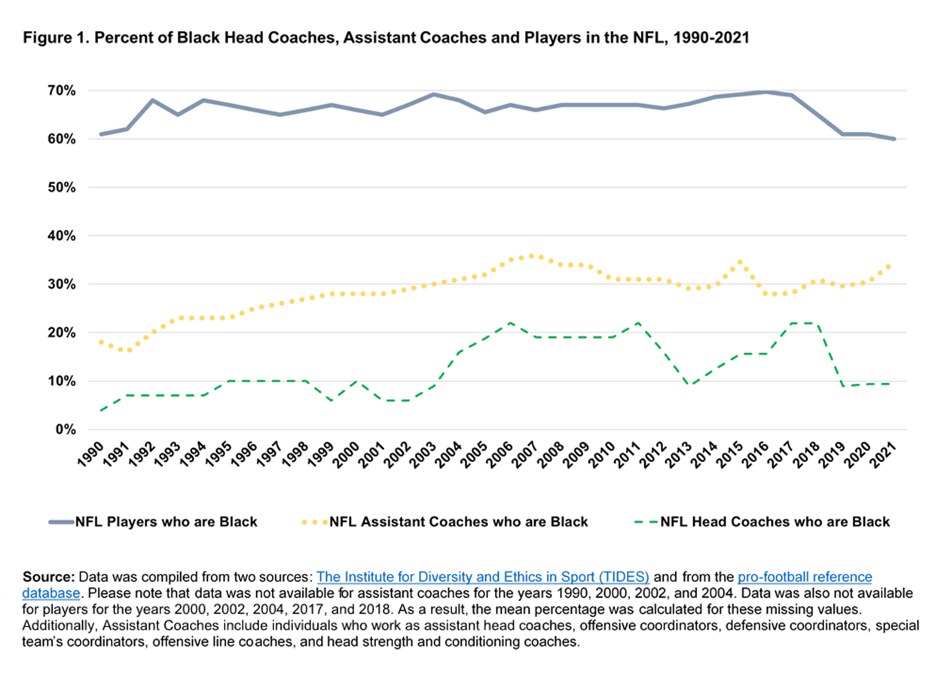

The Post series documented that there was an initial surge of Black head coaches after the 2003 implementation of the Rooney Rule, as shown in the dotted green line in Figure 1. But such opportunities quickly declined. By 2022, there were only four Black head coaches and fully half of all NFL teams have never had a Black head coach, even though in recent years, sixty to seventy percent of the league’s players have been Black.

The data in Figure 2 extend farther back in time, showing that only five percent of NFL head coaches in the past one hundred years have been Black. After implementation of the Rooney Rule in the 2000s, there was an increase in Black NFL head coaches debuting in the league. For example, although only 7.3% of head coaches were Black between 1990 and 1999 this number nearly tripled to 20.4% between 2000 and 2009.

On the surface, it appears that implementation of the Rooney Rule had a positive impact on the hiring of Black NFL head coaches, particularly between 2004 and 2011. Of the 45 NFL head coaches who debuted during this period, 13 (or 29%) were Black and 71% were white. However, 9 of these 13 (69%) new head coaches served on an interim basis and only four (Lovie Smith, Mike Tomlin, Jim Caldwell, and Hue Jackson) were appointed to the head coach position.

Figure 2. Year NFL Head Coaches Debuted, 1920-2022

| Black Head Coaches (N=26) | White Head Coaches (N=488) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 to 1979 (n=315) | 0.3% | 99.7% |

| 1980 to 1989 (n=40) | 2.6% | 97.4% |

| 1990 to 1999 (n=41) | 7.3% | 92.7% |

| 2000 to 2009 (n=54)* | 20.4% | 79.6% |

| 2010 to 2022 (n=66) | 15.4% | 84.6% |

| Total (N=514) | 5.1% | 94.9% |

Source

The Post notes an interesting departure from the data on the dearth of Black head coaches in the NFL: there is far more Black representation among interim head coaches. We devote the remainder of this piece to this understudied trend. The following question drives our analysis : If Black men are qualified enough to lead the team in the interim, why aren’t they qualified enough to lead the team permanently? Or, in other words: Why isn’t the position of interim-head coach a pathway to a permanent head coaching position for Black men?

This question has many possible answers. We begin with the list of reasons or excuses that NFL teams used to explain why they passed over otherwise-qualified Black candidates, which Troy Vincent, head of NFL football operations, provided to USA Today:

- “Never called plays

- Too many friends listed on potential coaching staff

- No previous game-clock management

- Unsure of their ability to motivate veteran players

- Didn’t interview well

- Lacked the necessary experience to lead

- Didn’t look the part

- Seemed nervous throughout the interview process

- Job is different than what it was previously”

We ask: Why wouldn’t a stint as an interim coach provide evidence of a coach’s play calling, clock management, ability to motivate, and leadership experience? Furthermore, wouldn’t a Black coach’s time as an interim head coach demonstrate that he can “look the part?” (whatever that may mean).

“Too many friends listed on the potential coaching staff?” Figure 3 shows that many NFL coaching rosters include a cadre of fathers and sons and sons-in-law, particularly on the staffs of white head coaches. Of the twelve coaching combinations, ten were held by white fathers and sons. The only two Black father-son coaching combinations include Marvin Lewis and Lovie Smith.

Figure 3: Father-Son Coaching Combinations

| Team | Father (position) | Son (position) |

|---|---|---|

| Bengals | Marvin Lewis (head coach) | Marcus Lewis (defensive assistant) |

| Buccaneers | Lovie Smith (head coach) | Mikal Smith (safety coach) |

| Chiefs | Andy Reid (head coach) | Britt Reid (quality control) |

| Chiefs | Marty Schottenheimer (head coach) | Brian Schottenheimer (assistant) |

| Rams | Jeff Fisher (head coach) | Brandon Fisher (assistant secondary) |

| Patriots | Bill Belichick (head coach) | Steve Belichick (coaching assistant) |

| Seahawks | Pete Carroll (head coach) | Nate Carroll (assistant WR coach) |

| Vikings | Mike Zimmer (head coach) | Adam Zimmer (LB coach) |

| Vikings | Norv Turner (offensive coordinator) | Scott Turner (QB coach) |

| Washington | Mike Shanahan (head coach) | Kyle Shanahan (offensive coordinator) |

Perhaps a Black applicant “seemed nervous during the interview” because he is fully aware of the racism in the NFL?

Or is it the case, as the authors of the Washington Post series conclude, that: “owners are most willing to entrust their franchises to Black men only when the season already has gone sideways.” It seems that a Black man will do in a pinch, when there is not much less to lose, but he is not to be trusted when winning is on the line.

As the data in the figures below illustrate, of the twenty-five Black men who have ever held head coaching positions in the NFL after 1989, nearly half (48%) served in some type of interim head coaching position over the course of their career compared to only fifteen percent of white coaches.

For example, in 1989, the first Black NFL head coach of the modern era, Art Shell, served as interim head coach of the Oakland Raiders after Mike Shanahan was fired. Art Shell was an offensive line coach for six seasons before stepping in to serve as head coach of the Raiders. Conversely, Shanahan spent only four seasons with the Denver Broncos as an offensive coordinator and receiving coach before leading the Raiders in 1988.

Figure 4. Career Trajectory among Black and White NFL Head Coaches, 1989-2022

| Black Head Coaches (n=25) | White Head Coaches (n=170) | |

|---|---|---|

| Served as an interim head coach during their career | 48% | 15% |

| Only served as an interim head coach | 20% | 4% |

| Served as a head coach BEFORE interim head coach position | 8% | 6% |

| Head coach career started AFTER serving as an interim head coach | 20% | 5% |

| Only served as a head coach; never served as an interim head coach | 52% | 85% |

| Total | 100% | 100% |

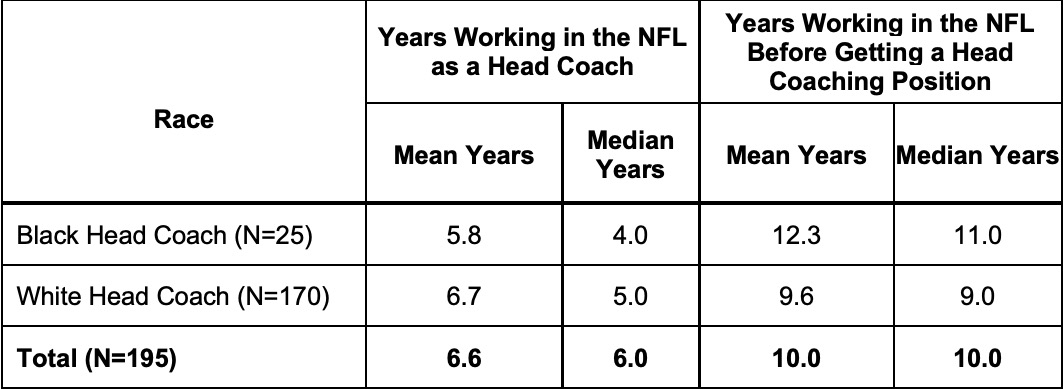

Additionally, Black head coaches have shorter coaching careers compared to white head coaches (5.7 years vs. 6.7 years). Black head coaches also spend more time in secondary roles in the NFL before earning head coaching jobs : 12.3 years vs. 9.6 years for white head coaches (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Mean and Median Years Working in the NFL as a Head Coach and Mean and Median Years Working in the NFL Before Getting a Head Coaching Position, 1989-2022

Furthermore, as data in the Post story make clear, Black men who have been appointed to the position of interim head coach are less likely to be retained than white men who are appointed to the same position.

As shown in Figure 6, from 1989 to 2021, nearly two-thirds (64%) of those appointed as interim head coaches were white and 36% were Black. But Black interim head coaches were more likely to be relegated to interim status, compared to their white counterparts who were more likely to serve as a head coach at some point before or after their interim positions.

Figure 6. Demographics of Interim Head Coaches, 1989-2021

| Frequency | Percent Black | Percent White | |

| Had been head coach before interim position | 13 | 16.7% | 42.3% |

| Became head coach after interim position only | 13 | 41.7% | 30.8% |

| Served as interim head coach only | 12 | 41.7% | 26.9% |

| Sub Total | 38 | 31.6% | 68.4% |

| Total (includes 4 who served twice in interim role) | 42 | 35.7% | 64.3% |

If You’re White, Winning Isn’t Everything

One logical explanation for the racial difference in the retention of Black interim head coaches would be that they don’t lead their teams to as many wins as white interim head coaches do. In fact, data from the Washington Post series demonstrate, “winning isn’t everything” and Black coaches are fired with better records than their white counterparts. For example, both Lovie Smith of the Chicago Bears (2012) and Jim Caldwell of the Detroit Lions (2017) were fired after posting winning records.

So perhaps the problem isn’t that a Black head coach might lose, it’s a fear that he might actually win.

Just a few years after the historic Super Bowl in 2007 that featured not one but two teams coached by Black men (Tony Dungy and Lovie Smith), the number of Black coaches in the NFL actually decreased.

There seems no evidence stronger than the 2007 Super Bowl to demonstrate that NFL owners are resistant to, or perhaps even afraid of, the possibility that Black men can successfully lead their teams to victory. If a Black coach wins, he must be retained, and owners must recalibrate their racial ideologies to incorporate facts that disrupt their understanding of the world and the role of Black men in it. It’s one thing to hire Black men to run up and down the field and dance in the end zone, but quite another to believe they have the intellectual capacity and leadership skills to lead a billion-dollar franchise. For the NFL to grant the latter demands that owners see Black men as their equal.

Recommended Reading:

Earl Smith. 2014. Race, Sport, and the American Dream. Durham, NC: CAP Press.

Harry Edwards. 2017. The Revolt of the Black Athlete. 50th anniversary edition. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Joel Rosen. 2014. Black Baseball, Black Business: Race Enterprise and the Fate of the Segregated Dollar. Oxford, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Victor Ray. 2019. “A Theory of Racialized Organizations.” American Sociological Review 84(1):26–53.

William Rhoden. 2006. Forty Million Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete. New York: Crown.