We recently introduced the idea of “astroturfing.” Coined to contrast with the idea of a “grassroots” movement (led and supported by “regular” people), an astroturf movement is one that looks like it’s grassroots, but is actually driven and funded by a corporation. But is it always easy to distinguish between astroturf and grass? F.T. Garcia sent in this confounding example.

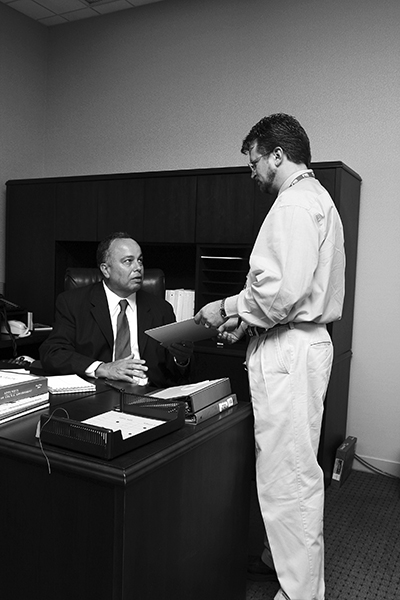

The Wall Street Journal reports that some labor unions are hiring non-union workers to “staff” picket lines, usually at or near minimum wage. In this picture, for example, employees-for-the-day protest on behalf of union workers for a union they do not belong to:

It turns out, protesting is costly. Workers have to take time off of work, travel to the location of the protest, pay for parking, make sure someone is taking care of their kids, etc. Plus it’s often hot and involves a lot of yelling and stomping. Accordingly, some unions decide that it’s easier and cheaper to hire protesters than it is to mobilize their own workers.

So, you tell me, astroturf or grassroots?

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.