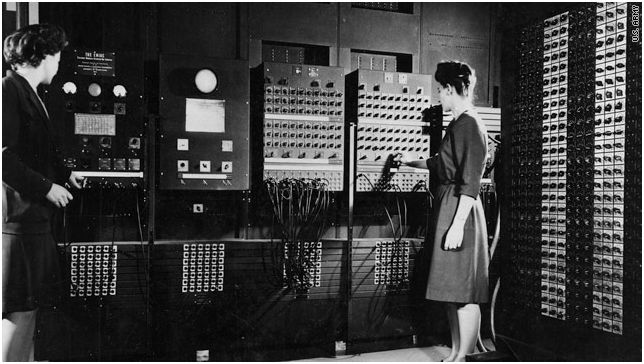

Many of us are familiar with the female blue-collar workers that took jobs in factories during World War II. It turns out, however, that women were also employed as mathematicians and computers (that’s “compute-ers”). In this photo, Jean Jennings Bartik and Frances Bilas Spence get ready to present an early computer to military officials in 1946:

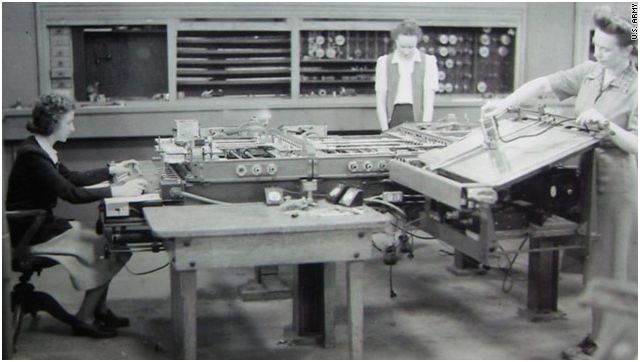

Women operating a “differential analyzer,” often checking the machine’s work by doing the math by hand:

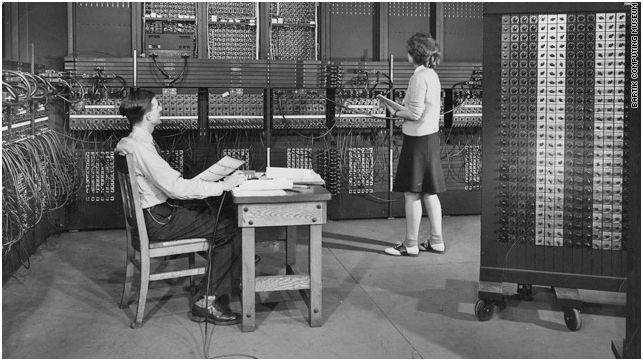

Jean Jennings Bartik in 1946 with an early computer and Arthur Burks:

Their work was top-secret and so they weren’t part of the “Rosie the Riveter”-style propaganda at the time. Post-World War II disinterest in women’s accomplishments allowed their stories to remain untold.

A new documentary, forwarded to us by Jordan G. and Dmitriy T.M., reveals these high-tech Rosies:

Via BoingBoing, photos from CNN.

See also our post on the feminist mythology surrounding the iconic “Rosie the Riveter” image (hint: it was about class, not gender). And you can buy Jean Jennings Bartik book, Pioneer Programmer, here.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.