Dr. Grumpy re-tells the fascinating story of the importation of camels to North America for use as beasts of burden. He begins:

Following the Mexican-American war, the United States found itself in control of a large desert, covering what’s now New Mexico & Arizona, and parts of Texas, California, and several other states. The U.S. Army needed to establish bases and supply lines in the area, both for the border with Mexico and the continuing wars with Indian tribes.

The railroad system was in it’s infancy, and there were no tracks through the area… The only way across was to use horses. But horses, like humans, are heavily dependent on water. This made the area difficult to cross, and vulnerable to attacking Apaches.

And so in 1855 Jefferson Davis, then U.S. Secretary of War (later to become President of the Confederacy during the Civil War), put into action an idea proposed by several officers: buy camels to serve in the desert. Congress appropriated $30,000 for the endeavor, and officials were sent to Turkey to do just that.

The next year they imported somewhere between 62 and 73 camels and, with them, 8 camel drivers all led by a man named Hadji Ali. Enter the U.S. Army Camel Corps.

Camels at an Army Fort:

(source)

(source)

Illustration of camels in camp:

(source)

(source)

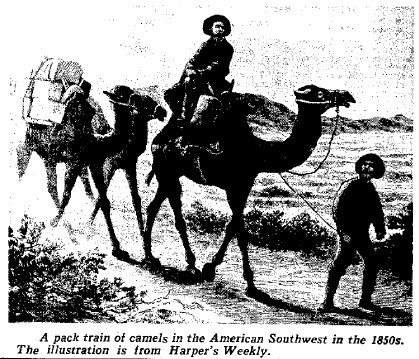

Camels on the go (1850s):

(source)

(source)

Says Dr. Grumpy:

They led supply trains all over, from Texas to California…

But there were problems. The Americans had envisioned combined forces of camels and horses, each making up for the deficiencies of the other. But horses and donkeys are frightened of camels, making joint convoys difficult and requiring separate corrals. The army was also unprepared for their intrinsically difficult personalities- camels bite, spit, kick, and are short-tempered. Horses are comparatively easy to handle.

Then came the start of the American Civil War, which focused military attention to the east. With troops pulled out of the American desert, and horses better suited to the eastern terrain, the camels were abandoned. Though Weird CA suggests that they were used in the war, Dr. Grumpy reports that most simply escaped into the desert. For a time, there was a wild camel population in the U.S.

Meanwhile, a former-solider and Canadian gold prospector, Frank Laumeister, figured that camels would be great pack animals for his new line of work. He bought a herd in 1862, but they didn’t work out so well in the rockier terrain. Plus:

The Canadians, like the Americans, discovered they weren’t easy to handle. The same problems of difficult disposition and spooking horses came up. In addition, they found camels would eat anything they found. Hats. Shoes. Clothes that were out drying. Even soap. And so, after a few years, the Canadians gave up on the experiment, too.

Laumeister on one of his camels:

Our original head camel driver, Hadji Ali, eventually got out of the camel business, but he never left America. He became a citizen in 1880, married a woman named Gertrudis Serna and had two children. He died in Arizona in 1902, having spent 51 years of his life in the U.S. You’ll find his tombstone in Quartzsite, Arizona labeled with the name “Hi Jolly,” the Americanized pronunciation of his full name.

(source)

The last sighting of a wild camel in North America was in 1941 near Douglas, Texas (source).

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.