Father’s Day advertisements are a peek into what we think dads are all about. As cultures change, advertising shifts too, giving us a peek into the social construction of fatherhood.

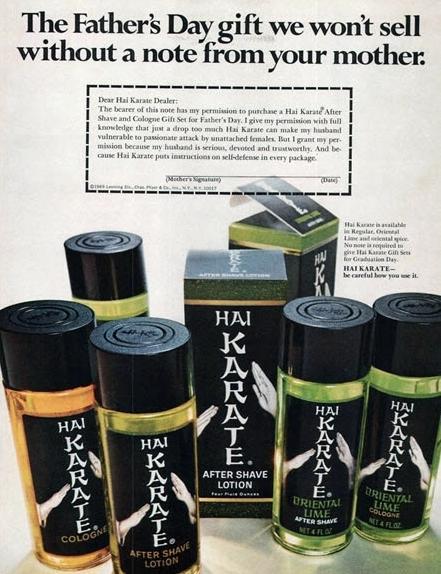

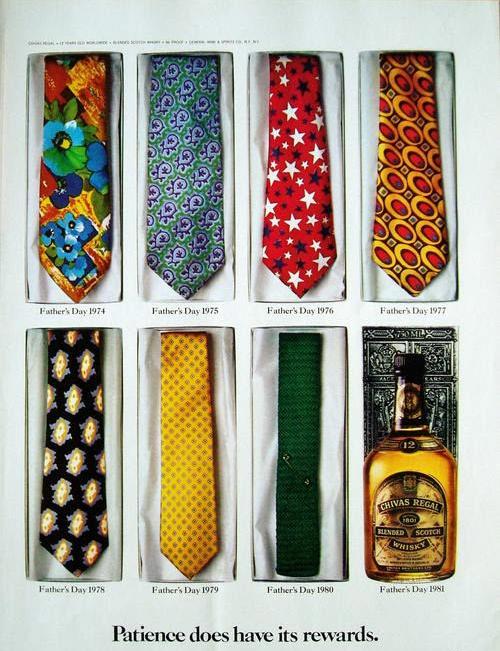

Karl Bakeman pointed us to a series of vintage Father’s Day ads at Retronaut. They label them with the range from 1943 to 1981. Perhaps we can have fun guessing which was when. According to these ads, great gifts for dads include recliners, whiskey, cologne, and a pack of smokes. Today the perfect Dad’s Day gift appears to be meat and meat.

Ties were timeless, until 1981:

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.