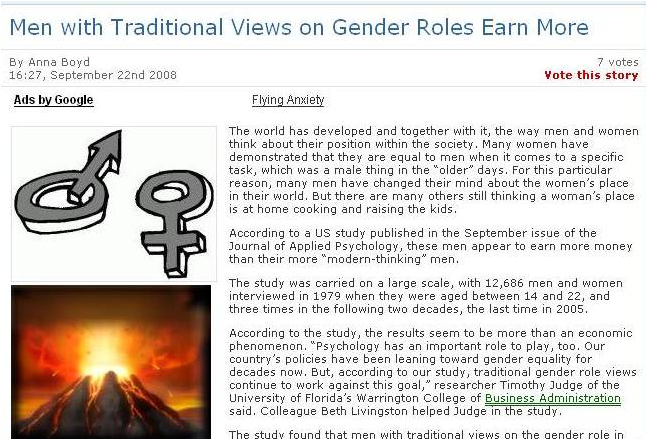

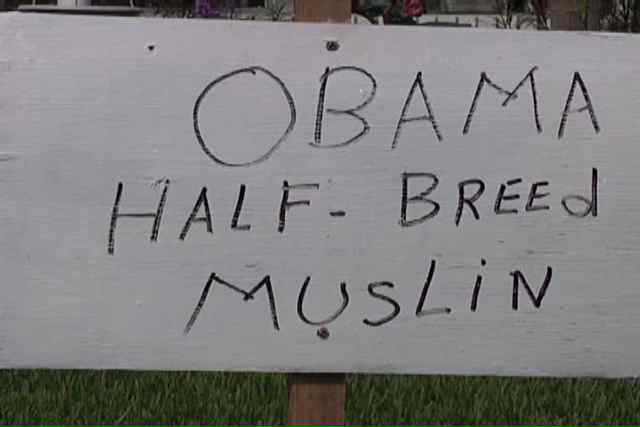

Jessica at Scatterplot notes the difference between the BBC coverage and the U.S. coverage of a recent research report noting that the real gender gap is between men who believe men should be breadwinners and women homemakers and everyone else (men who believe women and men should share in both breadwinning and homemaking, women who believe the same, and women who believe that they should be homemakers and men breadwinners) (i.e., at msnbc). Here are two screenshots of the coverage:

Did you catch the difference?