This is the first part in a series about how girls and women can navigate a culture that treats them like sex objects. Cross-posted at Ms., BroadBlogs, and Caroline Heldman’s Blog.

Around since the 1970s and associated with curmudgeonly second-wave feminists, the phrase “sexual objectification” can inspire eye-rolling. The phenomenon, however, is more rampant than ever in popular culture. Today women’s sexual objectification is celebrated as a form of female empowerment. This has enabled a new era of sexual objectification, characterized by greater exposure to advertising in general, and increased sexual explicitness in advertising, magazines, television shows, movies, video games, music videos, television news, and “reality” television.

What is sexual objectification? If objectification is the process of representing or treating a person like an object (a non-thinking thing that can be used however one likes), then sexual objectification is the process of representing or treating a person like a sex object, one that serves another’s sexual pleasure.

How do we know sexual objectification when we see it? Building on the work of Nussbaum and Langton, I’ve devised the Sex Object Test (SOT) to measure the presence of sexual objectification in images. I proprose that sexual objectification is present if the answer to any of the following seven questions is “yes.”

1) Does the image show only part(s) of a sexualized person’s body?

Headless women, for example, make it easy to see her as only a body by erasing the individuality communicated through faces, eyes, and eye contact:

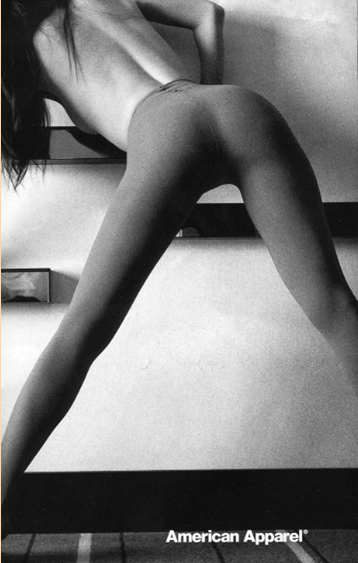

We get the same effect when we show women from behind, with an added layer of sexual violability. American Apparel seems to be a particular fan of this approach:

2) Does the image present a sexualized person as a stand-in for an object?

The breasts of the woman in this beer ad, for example, are conflated with the cans:

Likewise, the woman in this fashion spread in Details in which a woman becomes a table upon which things are perched. She is reduced to an inanimate object, a useful tool for the assumed heterosexual male viewer:

Or sometimes objects themselves are made to look like women, like this series of sinks and urinals shaped like women’s bodies and mouths and these everyday items, like pencil sharpeners.

3) Does the image show a sexualized person as interchangeable?

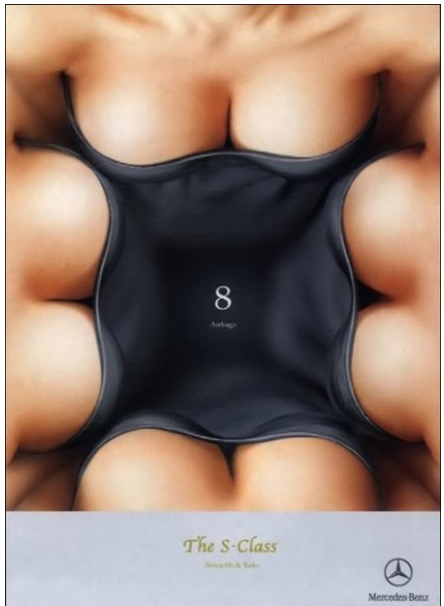

Interchangeability is a common advertising theme that reinforces the idea that women, like objects, are fungible. And like objects, “more is better,” a market sentiment that erases the worth of individual women. The image below advertising Mercedes-Benz presents just part of a woman’s body (breasts) as interchangeable and additive:

This image of a set of Victoria’s Secret models, borrowed from a previous SocImages post, has a similar effect. Their hair and skin color varies slightly, but they are also presented as all of a kind:

4) Does the image affirm the idea of violating the bodily integrity of a sexualized person that can’t consent?

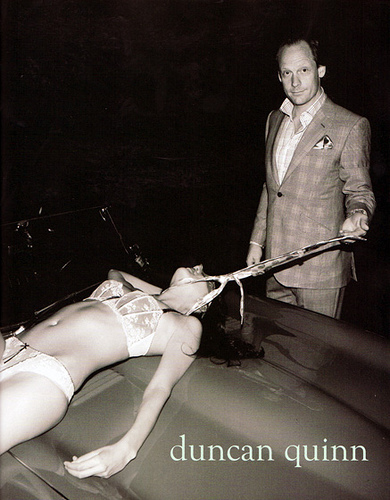

This ad, for example, shows an incapacitated woman in a sexualized positionwith a male protagonist holding her on a leash. It glamorizes the possibility that he has attacked and subdued her:

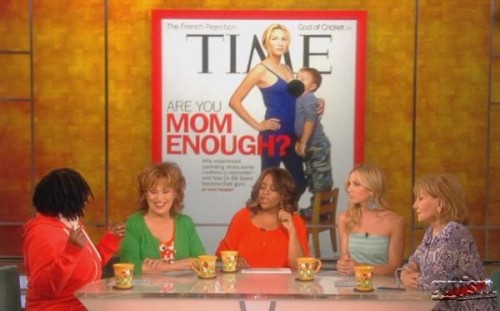

5) Does the image suggest that sexual availability is the defining characteristic of the person?

This ad, with the copy “now open,” sends the message that this woman is for sex. If she is open for business, then she presumably can be had by anyone.

6) Does the image show a sexualized person as a commodity (something that can be bought and sold)?

By definition, objects can be bought and sold, but some images portray women as everyday commodities. Conflating women with food is a common sub-category. As an example, Meredith Bean, Ph.D., sent in this photo of a Massive Melons “energy” drink sold in New Zealand:

In the ad below for Red Tape shoes, women are literally for sale:

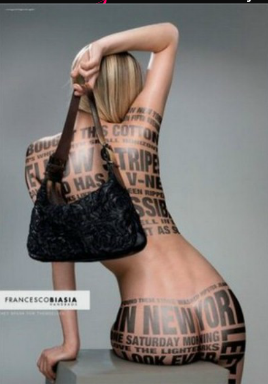

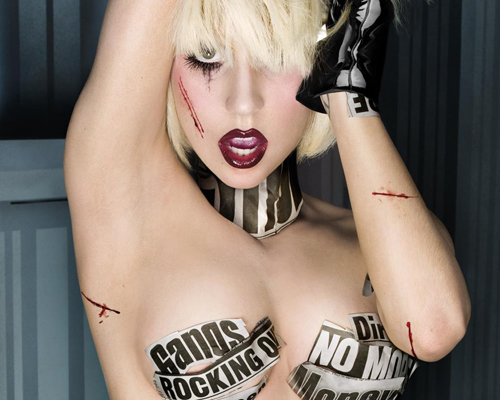

7) Does the image treat a sexualized person’s body as a canvas?

In the two images below, women’s bodies are presented as a particular type of object: a canvas that is marked up or drawn upon.

——————

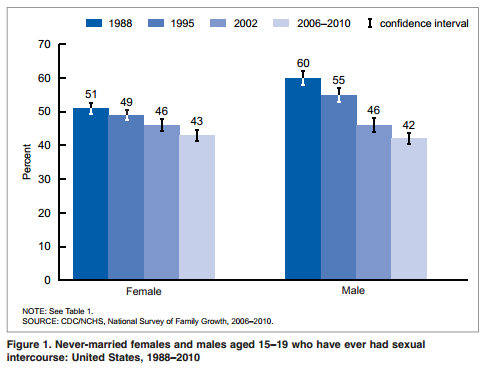

The damage caused by widespread female objectification in popular culture is not just theoretical. We now have over ten years of research showing that living in an objectifying society is highly toxic for girls and women, as is described in Part 2 of this series.

Caroline Heldman is a professor of politics at Occidental College. You can follow her at her blog and on Twitter and Facebook.