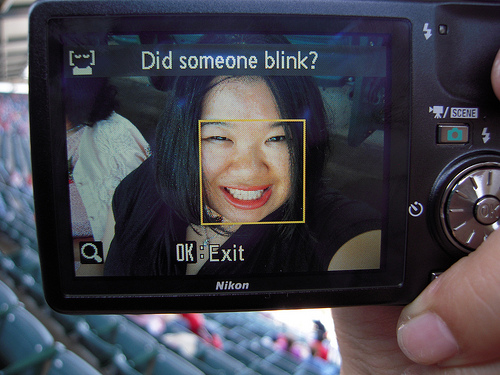

This new commercial for Kentucky Fried Chicken’s grilled option features an assortment of people and, then, two Asian guys in Asian-looking garb with fake Asian accents acting like fools (found at Racialicious):

I’m sort of speechless here. (1) I can’t imagine how KFC could have thought that this made any sense at all. (2) I don’t understand how they could fail to notice that this is racist.

Then again, as we argued about the recent Sotomayor cover, maybe the truth is that it’s simply fine to be racist these days as long as it’s shrouded in the thinnest film of “humor.”

In a post on Racialicious, Arturo Garcia made a point about Sasha Baron Cohen’s work that resonated with me deeply and, I think, captures how I feel about this new brand of satirical humor/hipster racism:

Maybe we’ve had it wrong all along – Borat and the upcoming [film] Bruno aren’t comedies at all – they’re horror movies, holding up the mirror to our new idea of funny.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.