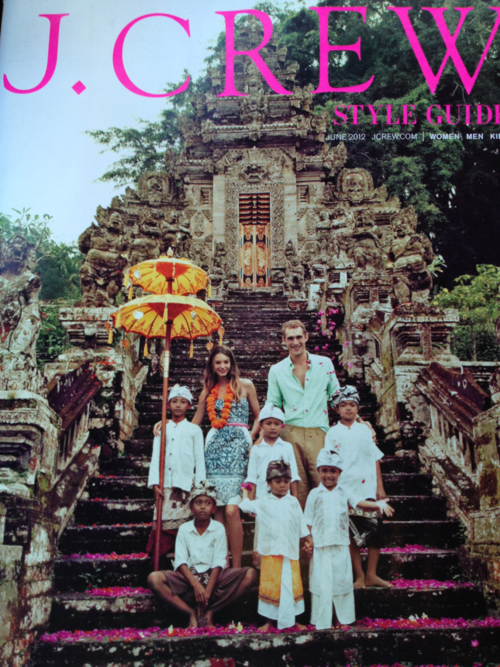

My post on the centrality of whiteness in fashion photos — whether magazine photos, catalogs, or ads — inspired several readers to send in other examples related to this trend.

YetAnotherGirl and Julian S. sent in a link to a Jezebel post about the new J.Crew catalog, which presents the two models in J.Crew clothing amid a group of local children, who are used to help signal the exoticism of the location:

Marianne sent in a couple of ads for Naf Naf, a French fashion brand, that show a slight variation, utilizing ethnic/cultural differences within Europe. They show a “luminous, lightning-blond caucasian woman and the dark, anonymous and yet welcoming bohemians,” seemingly meant to evoke popular imagery of the Romani.

And finally, H. pointed out Louis Vuitton’s “Journey” commercial, which she actually saw at an indie movie theater. It provides an interesting counterpoint, as groups other than Caucasians can be included as central characters in the narrative, as long as they are privileged LV consumers, with others presented in the more peripheral setting-the-tone role. As H. explains,

In this ad they include the story line of the (presumably African?) black man who is dressed in an elegant Western-style linen suit, but who is barefoot and rubbing the dust off of an old family photo. An interesting racial counterpoint — and one which suggests a metanarrative which is not only about race but also quite pointedly about class.

Take a look:

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.