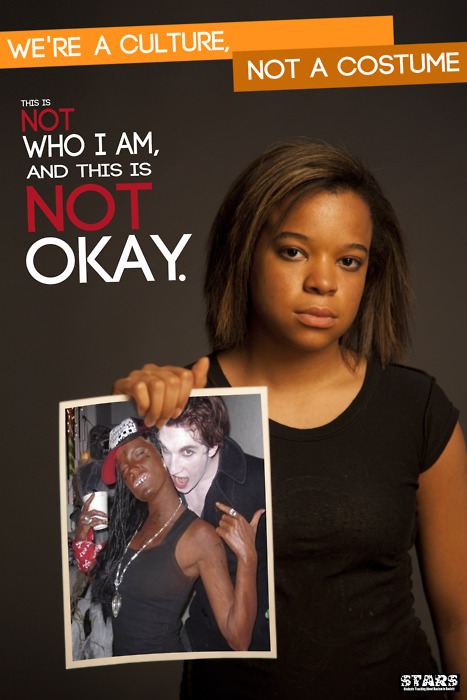

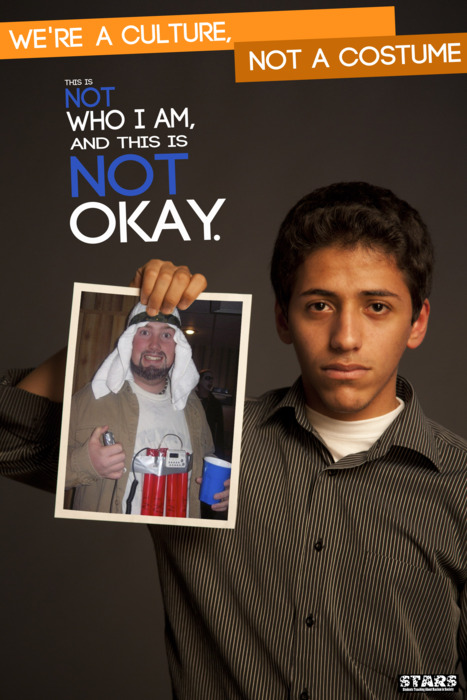

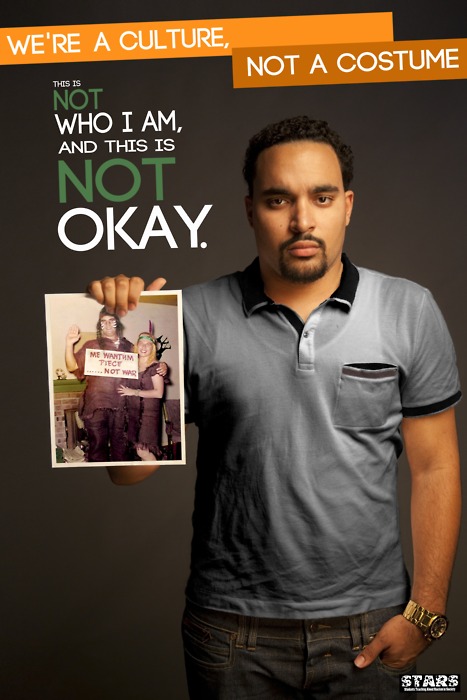

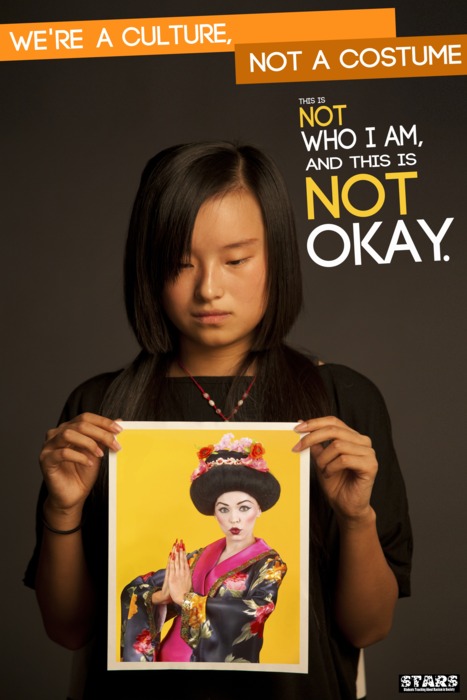

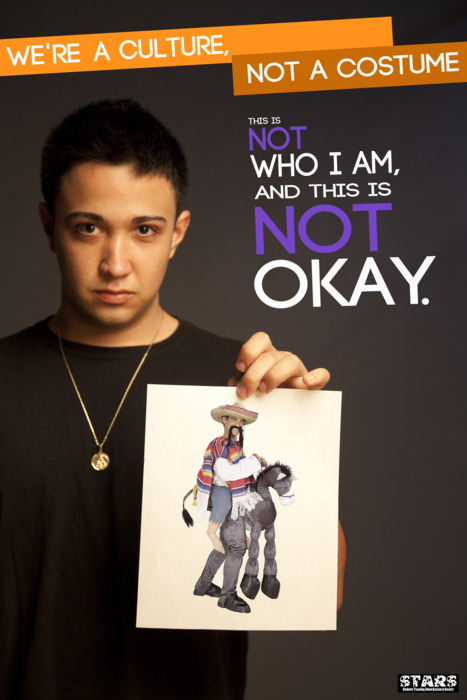

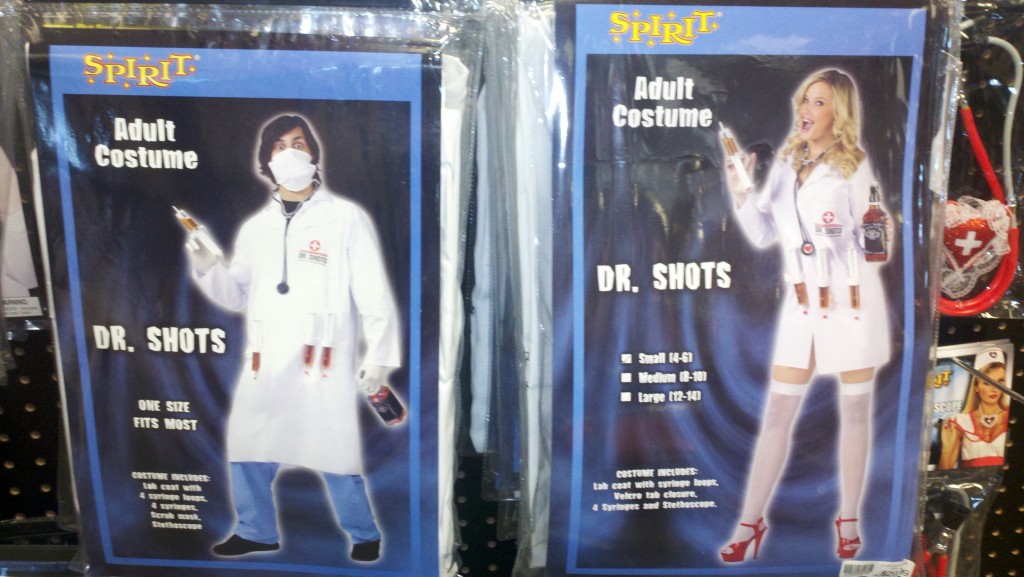

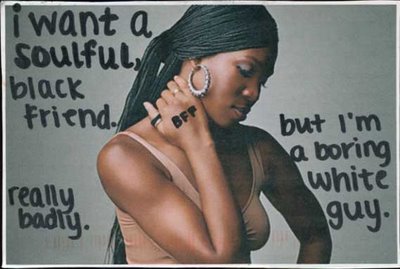

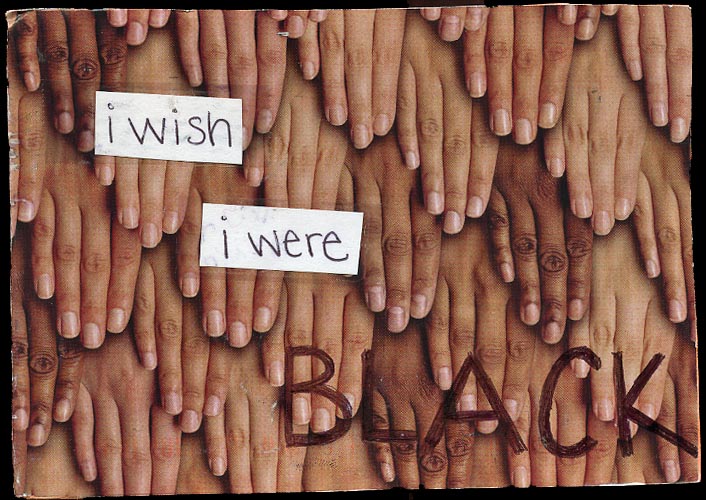

Eleven readers sent in this wonderfully simple campaign to discourage people from dressing up like racial or ethnic caricatures for Halloween. Or dressing their dogs up as such.

Kudos to the STARS students at Ohio University behind this campaign! The costumes that they’re holding up, by the way, are real; we’ve featured several of them in previous years at SocImages.

Thanks to Norma M., Amias, Katrin, Dmitriy T.M., A.M.S., Joe F., Sarah D., Sara P., Molly, Patrick C., and Washburn University professor Sangyoub Park! It’s exciting that so many readers sent this in and that the campaign got so much attention. It suggests that many people were hungry for a clear message against this phenomenon.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.