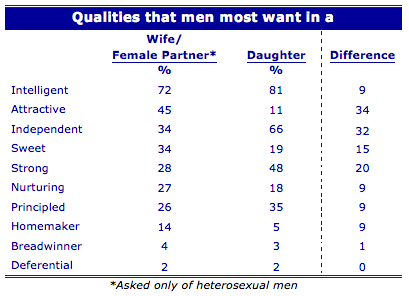

New data collected for the Shriver Report offers a telling insight into modern marriage. They asked 818 men representative of the adult U.S. population to choose three “qualities that [they] most want” in a daughter from a set of 10. Offering the same list, they asked which qualities they wanted in a wife or female partner. Intelligence topped both lists but, from there, responses diverged.

This is your image of the week:

Men were pretty consistent in what they wanted for their daughters. A majority said intelligence (81%) and two thirds (66%) said independence. Almost half (48%) said they wanted their daughters to be strong.

But, as a group, they were significantly more ambivalent about what they wanted from wives. Some wanted intelligence, independence, and strength, but many fewer wanted that in wives compared to daughters: 34% said they wanted independent wives and 28% said they wanted strong ones. Compared to what they wanted for daughters, they were much more likely to say they wanted attractiveness (45% vs. 11%), sweetness (34% vs. 19%), nurturing (27% vs. 18%), and homemaking (14% vs. 5%) from wives.

This is fascinating data. It looks like the majority of men want strong, successful, independent daughters, but there is still a significant number who hope for wives who are willing to put their husbands before themselves.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.