Despite the cellphone video of two police officers killing Kajieme Powell, there is some dispute as to what happened (see this account in The Atlantic). Was Powell threatening them; did he hold the knife high; was he only three or four feet away?

The video is all over the Internet, including the link above. I’m not going to include it here. The officers get out of the car, immediately draw their guns, and walk towards Powell. Is this the best way to deal with a disturbed or possibly deranged individual – to confront him and then shoot him several times if he does something that might be threatening?

Watch the video, then watch London police confronting a truly deranged and dangerous man in 2011. In St. Louis, Powell had a steak knife and it’s not clear whether he raised it or swung it at all. The man in London has a machete and is swinging it about.

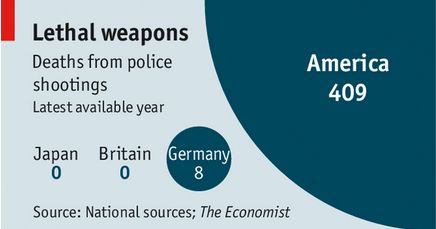

Unfortunately, the London video does not show us how the incident got started. By the time the recording begins, at least ten officers were already on the scene. They do not have guns. They have shields and truncheons. The London police tactic used more officers, and the incident took more time. But nobody died. According to The Economist:

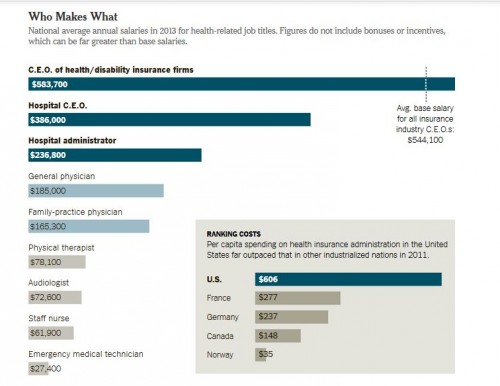

The police in and around Ferguson have shot and killed twice as many people in the past two weeks (Mr Brown plus one other) as the police in Japan, a nation of 127m, have shot and killed in the past six years. Nationwide, America’s police kill roughly one person a day.

The article includes this graphic:

I’m sure that the Powell killing will elicit not just sympathy for the St. Louis police but in some quarters high praise – something to the effect that what they did was a good deed and that the victims got what they deserved. But righteous slaughter is slaughter nevertheless. A life has been taken.<

You would think that other recent videos of righteous slaughter elsewhere in the world would get us to reconsider this response to killing. But instead, these seem only to strengthen tribal Us/Them ways of thinking. If one of Us who kills one of Them, then the killing must have been necessary and even virtuous.

Originally posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.