Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

What we don’t talk about when we don’t talk about class. That was the title I wanted to use, but it was too long, and besides, there are already too many of these Raymond Carver variants.

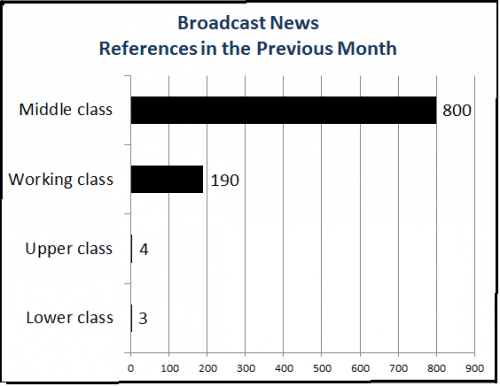

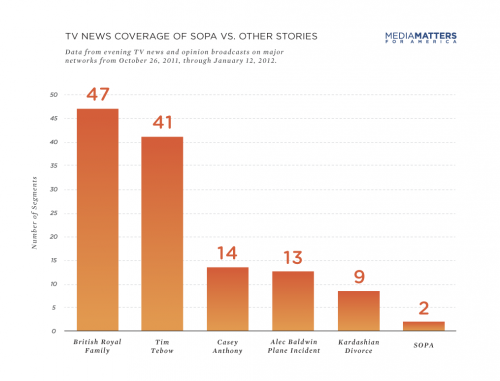

Class seems to have disappeared from public discourse, except for the Republicans’ insistence that to mention inequality at all is to engage in “class warfare.” The only class we hear about, whether from politicians or the media, is the middle class. Here, for example, are the results of a Lexis-Nexis search of news transcripts in the previous month.

On TV news, the upper and lower class do not exist.

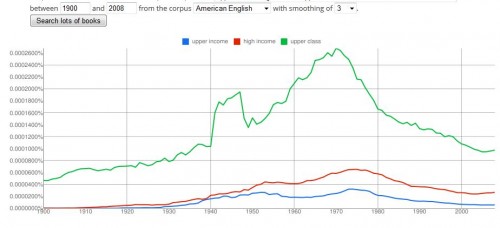

So how do we talk about those at the top and bottom of society? The discussion of inequality is now all about income. While “lower class” and “upper class” had only three and four mentions, respectively, in this same period, income terms (high, upper, low, lower) numbered over 300.

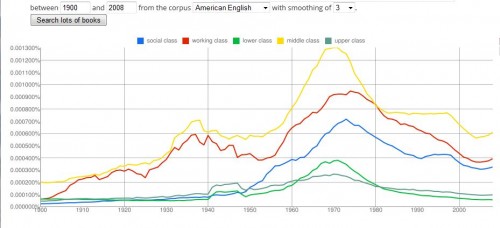

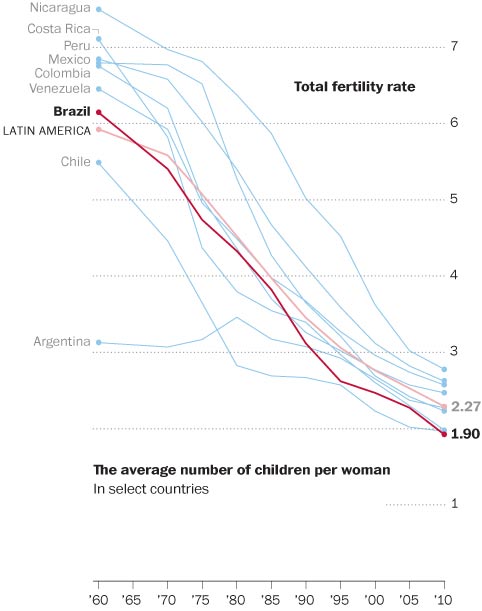

For some historical perspective, I looked at Google Ngrams for the frequency of class terms in books.

The pattern for upper class is similar — a large decline in class talk, a much smaller decrease in income talk — though class references still outnumber income references.

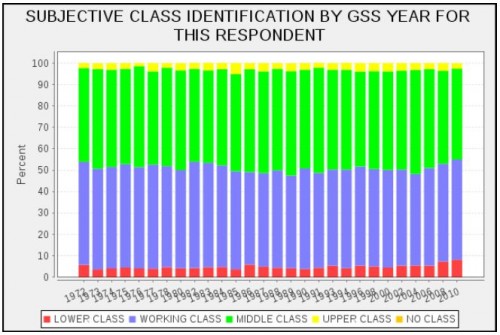

From the media, you get the impression that except for a handful of people at the top and the bottom, there really is only one class in America — the middle class — and that the working class has faded into history. Yet the GSS subjective social class item (“Which class would you say you belong in?”) gets the same results as it did in 1972: a roughly equal split between “middle” and “working” that accounts for 9 out of 10 Americans.