We’re celebrating the end of the year with our most popular posts from 2013, plus a few of our favorites tossed in. Enjoy!

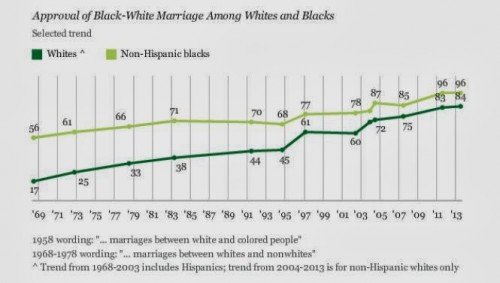

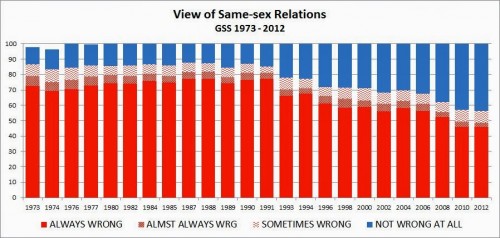

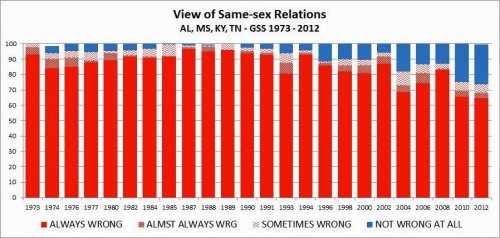

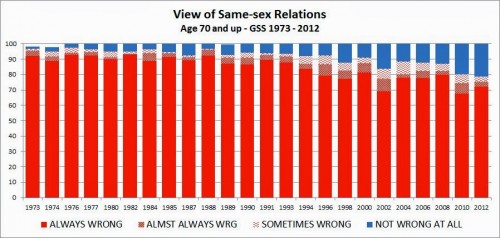

We’ve seen a real shift in support for the issue and acceptance of homosexuality in general. Since 2011, the majority of Americans are in favor of extending marriage to same-sex couples and the trend has continued.

What is behind that change? The Pew Research Center asked 1,501 respondents whether they’d changed their minds about same-sex marriage and why. Here’s what they found.

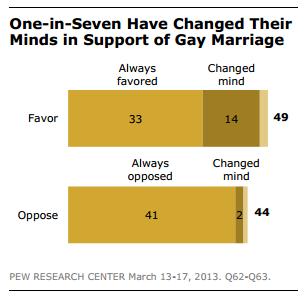

The overall trend towards increasing support is clear in the data. Fourteen percent of Americans say that they used to oppose same-sex marriage, but they now support it. Only 2% changed their mind in the other direction.

People offered a range of reasons for why they changed their minds. The most common response involved coming into contact with someone that they learned was homosexual. A third of respondents said that knowing a gay, lesbian, or bisexual person was influential in making them rethink their position on gay marriage. This is consistent with the Contact Hypothesis, the idea that (positive) experiences with someone we fear or dislike will result in changes of opinion.

As you can see, lots of other reasons were common too. A quarter of people said that they, well, “evolved”: they grew up, thought about it more, or more clearly. Nearly as many said that they were simply changing with the times or that a belief that everyone should be free to do what they want was more important than restricting the right to marry.

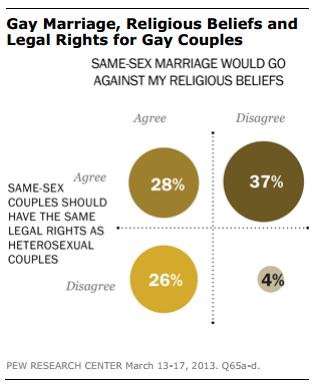

I thought that the 5% that said they’d changed their minds for religious reasons were especially interesting. Support for same-sex marriage is rising in every demographic, even among the religious. Following up on this, Pew offers an additional peek into the minds of believers. The table below shows that 37% of the religious both believe that same-sex marriage is compatible with their belief and support it, but an additional 28% who think marriage rights would violate their religious belief are in favor of extending those rights nonetheless.

While we’ve been following the trend lines for several years, it’s really interesting to learn what’s behind the change in opinion about same-sex marriage. Contact with actual gay people — and probably lovable gay and lesbian celebrities like Ellen and Neil Patrick Harris — appears to be changing minds. But the overall trend reflects real shifts in American values about being “open,” valuing “freedom” and “choice,” extending “rights,” and accepting that this is the way it is, even if one personally doesn’t like it.

Cross-posted at BlogHer and Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.