We’ve highlighted the ways in which society portrays men as people and women as women many times over. So many times, in fact, that we started a Pinterest collection. There are two scenarios in which men are the default person: (1) masculine spaces, like the workplace and politics, and (2) neutral spaces that aren’t associated with men or women, like museums and the internet.

When something is distinctly feminized, however, things flip. @jessimckenzi and @freedenoeur forwarded us a pointed example: a brand of lotion called “everyone.” Everyone lotion comes in two types: everyone lotion “for everyone and every body” and everyone lotion for men:

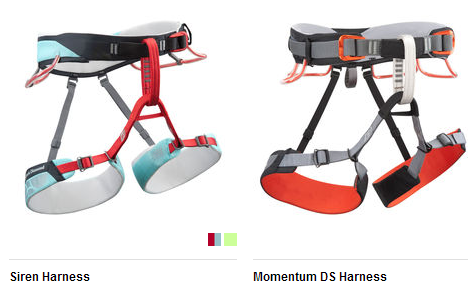

This practice reminds us who belongs where by making one gender or the other the neutral participant and then adding a modifier in order to selectively include the other sex. Another example of this phenomenon is the masculinizing of feminine products in order to sell them to men and the feminizing of masculine products to sell them to women. Together these practices affirm and naturalize gender-based segregation in our social spaces and activities.

This practice reminds us who belongs where by making one gender or the other the neutral participant and then adding a modifier in order to selectively include the other sex. Another example of this phenomenon is the masculinizing of feminine products in order to sell them to men and the feminizing of masculine products to sell them to women. Together these practices affirm and naturalize gender-based segregation in our social spaces and activities.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.