I don’t know for sure what holidays are like at your house, but if they resemble holidays at my house, and most houses in the US, women do almost all of the holiday preparation: decorating, gift buying and wrapping, invitations, neighborhood and church activities, cooking, cooking, more cooking, and cleaning.

Holidays are moments in the year when women, specifically, have extra responsibilities. I distinctly remember my own beloved stepmother telling me — stress making her voice taut — that she just wanted everyone to have a nice Thanksgiving. She would work herself silly to do and have all the right things so that everyone else would have a good time. Multiple this by 10 at Christmas.

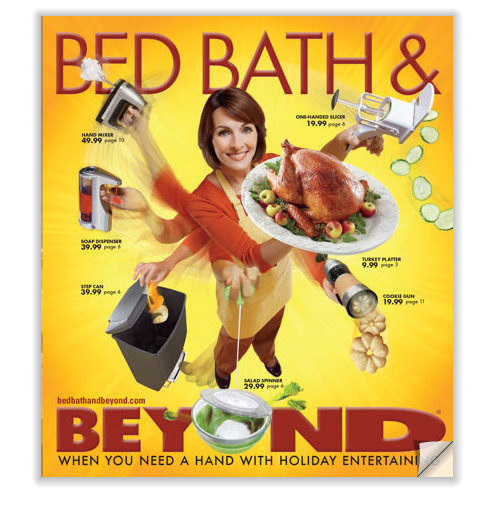

This Bed, Bath, & Beyond ad, sent in by Jessica E. and Jessica S., reminded me of the crazy workload that accompanies holidays for women:

Alone with the responsibility of making a holiday for everyone else, the woman manages to mobilize technology and goods from BB&B to make it happen. Ironically, the text reads: “When you need a hand with holiday entertaining,” but actual human help in the form of hands is absent. Apparently it’s easier for women to grow five extra arms than it is to get kids and adult men to pitch in.

Alone with the responsibility of making a holiday for everyone else, the woman manages to mobilize technology and goods from BB&B to make it happen. Ironically, the text reads: “When you need a hand with holiday entertaining,” but actual human help in the form of hands is absent. Apparently it’s easier for women to grow five extra arms than it is to get kids and adult men to pitch in.

Anyhoo, be a peach and give your mom a hand this holiday season.

Originally published in 2009.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

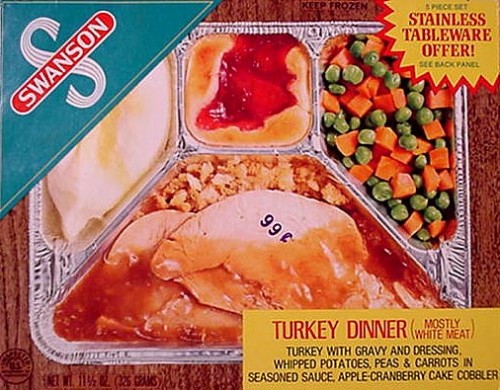

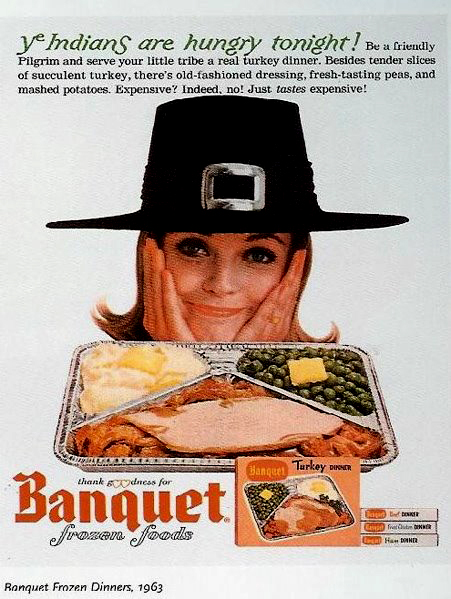

Pre-prepared frozen meals pre-dated the Swanson “TV dinner,” but it was Swanson who brought the aluminum tray — previously only seen in taverns and airplanes — into the home.

Pre-prepared frozen meals pre-dated the Swanson “TV dinner,” but it was Swanson who brought the aluminum tray — previously only seen in taverns and airplanes — into the home.