Flashback Friday.

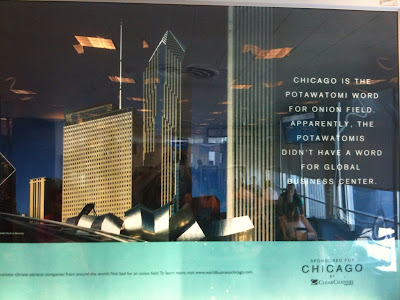

I was waiting for my connecting flight at Chicago O’Hare, and spotted this advertisement on the opposite side of our gate. It reads:

This is an example of the use of Indigenous language and imagery that many people wouldn’t think twice about, or find any inherent issues with. But let’s look at this a little deeper:

- The use of past tense. It’s not “The Potawatomis don’t have a word for…” it’s “The Potawatomis didn’t…” Implying that the Potawatomi no longer exist or are using their language.

- The implication that “Indians” and “Global Business Center” aren’t in congruence. Which is assuming that Natives are static, unchanging, and unable to be modern and contemporary. “Potawatomi” and “Onion Field” are fine together, because American society associates Indians with the natural world, plants, animals, etc. But there is definitely not an association between “Potawatomi” and “Global Business”.

But, in reality, of course Potawotomis still exist today, are still speaking their language, and do have a word for Global Business Center (or multiple words…).

Language is constantly evolving, adapting to new technology (remember when google wasn’t a verb?) and community changes. I remember reading a long time ago in one of my Native studies classes about the Navajo Nation convening a committee to discuss how one would say things like “computer” or “ipod” in Navajo language, in an effort to preserve language and culture and promote the use of Navajo language among the younger generation.

In fact, here’s an awesome video of a guy describing his ipod in Navajo, complete with concepts like “downloading” (there are subtitles/translations):

Native peoples have been trading and communicating “globally” for centuries, long before the arrival of Europeans. To imply that they wouldn’t have the ability to describe a “Global Business Center” reeks of a colonialist perspective (we must “civilize” the savage! show him the ways of capitalism and personal property, for they know not of society!).

Thanks, Chicago, for giving me one more reason to strongly dislike your airport.

Originally posted in 2010.

Adrienne Keene, EdD is a graduate of the Harvard Graduate School of Education and is now a postdoctoral fellow in Native American studies at Brown University. She blogs at Native Appropriations, where this post originally appeared. You can follow her on Twitter.