Originally posted in 2012; re-posted because tomorrow is the 145th Belmont Stakes, the 3rd and final leg of the Triple Crown in thoroughbred horse racing. This is the dark side of the sport.

In humans you never see someone snap their leg off running in the Olympics. But you see it in horse racing.

These words, spoken by the equine medical director for the California Racing Board, summarize the truly terrifying absurdity that is horse racing today. A team of investigative reporters at the New York Times has found that over 1,200 horses die at race tracks every year in the U.S. Many of them die immediately after a race, euthanized after their bodies literally crumble underneath them. Their legs break, unable to withstand the forces that the horses exert upon their bodies. People in the industry call it, euphemistically, a “break down.” It occurs 1 out of every 200 times a horse starts a race.

All of these horses are being ridden by a jockey who is pitched off when the horse falls. Moving at upwards of 50 miles an hour, and in the midst of many other horses running at top speed, jockeys are often seriously injured and sometimes killed. Currently there are over 50 permanently disabled jockeys receiving financial assistance from their professional trade association. Jacky Johnson, for example, was paralyzed from the neck down after his horse, Phire Power, broke its leg during a race. He will need a respirator for the rest of his life; Phire Power was euthanized on the track.

Why is this happening? Because we are making it so.

First, race horses are bred in order to run as fast as possible. Short legs and thick bones slow a horse down, while longer, more delicate legs give them longer strides. Breeders, then, have an incentive to build horses who are both faster and more fragile.

Second, owners may be putting these horses on the track too young. Horses typically start getting raced at 2 to 3 years old, very young for an animal with a lifespan of 30 years. Some argue that the bodies of young horses are not ready to handle the physical demands of racing. For instance, the 2-year-old horse Teller All Gone broke its leg during a race; it had to be euthanized.

The owners dumped his body at a junkyard.

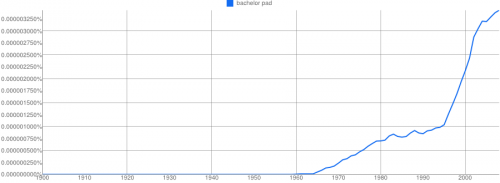

Third, there is the drug problem. Many trainers illegally give their horses performance-enhancing drugs. Many of them are experimental and are not yet or cannot be tested for. These include “chemicals that bulk up pigs and cattle before slaughter, cobra venom, Viagra, blood doping agents, stimulants and cancer drugs.”

Built for speed and not safety, on the track too young, and amped up on steroids and other performance-enhancers, these horses are pushed to their limits. Just this week Doug O’Neill, the trainer of I’ll Have Another, the horse set to win this year’s Triple Crown, was fined after his horse tested positive for performance enhancing drugs.

Even more problematic than the doping is the legal practice of giving horses pain-relieving drugs, including cocaine. These mask the pain signals that would otherwise tell a horse to slow down or be careful on the track and also increase that chances that the track veterinarian will miss an injury when clearing the horse to race. The NYT reports that “[a]s many as 90 percent of horses that break down had pre-existing injuries” and they argue pain-masking drugs “pose the greatest risk to horse and rider.” The Louisiana Racing Commission call it “a recipe for disaster.”

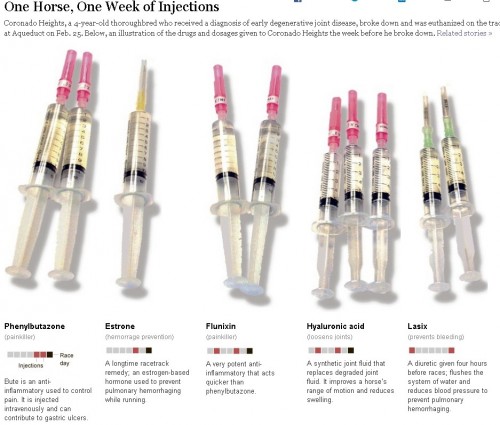

The drugs detailed below are what were given to Coronado Heights in the week before he collapsed and was euthanized on the track:

Horse racing is subject to regulation, but these vary by state and are typically very poorly enforced, bringing us to the fourth reason why we see so much tragedy on race tracks. The punishment for violations is insignificant, sometimes only a warning:

Trainers in New Mexico who overmedicate horses with Flunixin get a free pass on their first violation, a $200 fine on the second and a $400 fine on the third, records show… [the state also] wipes away Flunixin violations every 12 months… To varying degrees, the picture is similar nationwide. Trainers often face little punishment for drug violations, and on the rare occasions when they are suspended, they are allowed to turn their stables over to an assistant.

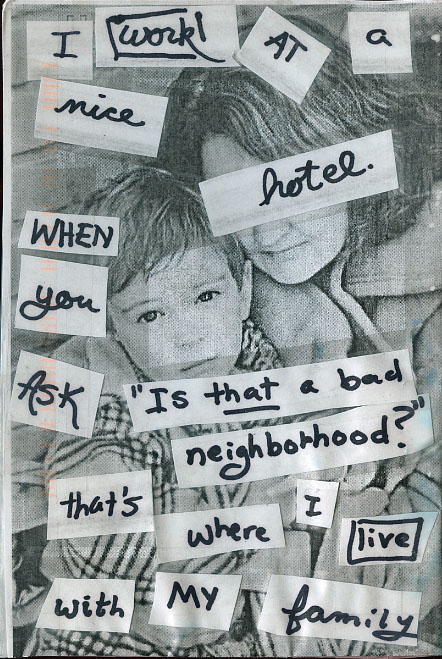

When it comes down to it, many owners and trainers are willing to risk a horse’s life for the chance at the prize money and the less likely a horse is to win, the less they’re worth to the owner, so the harder they’re willing to push it.

The economic incentive to run horses till they die may seem to apply to the highest stakes racing but, in fact, it’s at the lowest end that we see the most disregard for the safety of horses and their jockeys. In the backyards of those casinos where racetracks are now part of the attraction (often referred to as “racinos”), horses and jockeys are a dime a dozen, and the money gives people a reason to break the rules. Meanwhile, the casino tracks are low profile, so they receive even less regulatory attention.

The use of the phrase “break down” to describe a horse who has snapped its own bones in the process of entertaining and enriching human beings is an indication of how nonchalantly industry figures approach this problem. It suggests that these animals, and perhaps their jockeys as well, have been thoroughly objectified: cars break down, air conditioners break down, we break down boxes. The language entirely fails to capture what is happening to these horses. It may very well, however, describe what has happened to the industry and to the basic humanity of its most culpable beneficiaries.

Death at the Track:

Visit the New York Times to watch “The Rise of the Racinos” and “A Jockey’s Story.”

Lisa Wade and Gwen Sharp are professors of sociology. You can follow Gwen on Twitter and Lisa on Twitter and Facebook. They have also written about the abuse of Tennessee Walking Horses.