Steve Grimes, a once guest blogger who will be starting a sociology PhD program at Rutgers this fall, asked us to comment on the new “man aisle” in a grocery story in one of my old haunts, the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

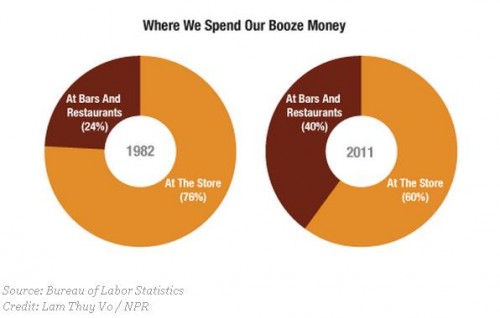

The New York Post reports that the store COO and CEO conceived of the idea after reading a study showing that 31% of men now shop for their families, compared to 14% in the 1980s. Ironically, the man aisle they designed doesn’t suggest that men are productive and useful members of their families. Instead, it reinforces the notion that men are all about leisure. The items sold — you already know what they are — include condoms, Ramen noodles, beer, snack foods, and a surprising amount of condiments.

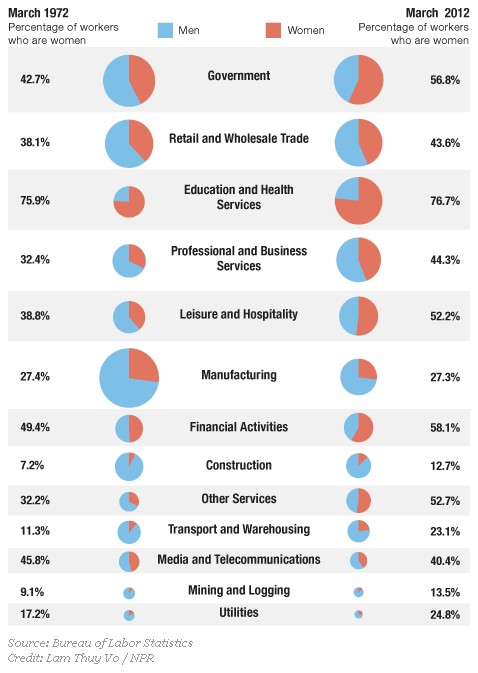

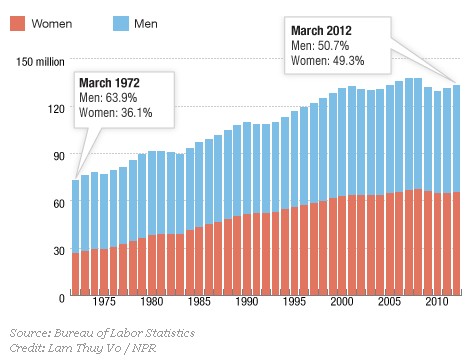

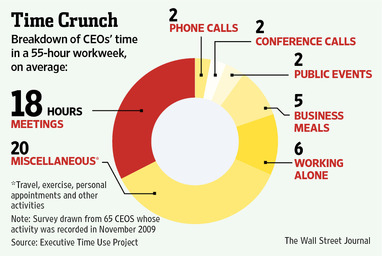

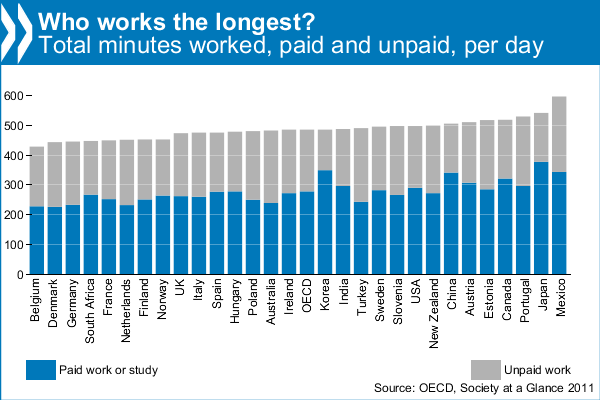

Because women are as likely to work for pay as men are, but continue to be held more responsible for housework and childcare, men do, in fact, enjoy more leisure time than women (in the U.S., almost 40 extra minutes a day). Media frequently portray women as responsible for families or hard-working careerists and men as eager for nothing but a good time. We see it in “for him” and “for her” news items and contrasting magazine content, and this idea is part of the message of the man aisle too.

Nothing about the man aisle suggests that he’s buying for anyone but himself, except insofar as he might be stocking a man cave for his man friends. This is unfortunate, because many men are productive and useful members of their families. Also, some men hate beer, are allergic to wheat, are on diets, and think beef jerky is gross. These men are invisible here too.

Meanwhile, the very presence of a single aisle for men marks the rest of the grocery store — the toilet paper, the diapers, the cleaning products, the greeting card aisle (*shudder*), the baking supplies, and the healthy food that you have to cook — as for women.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.